Tchicaya U Tam’Si is a monument of modern African literature. A specialist in his work, the literary critic Boniface Mongo-Mboussa devotes a luminous biographical essay to him. Both narrative and analytical, the work illuminates the abysses and the pangs of a life lived to the dregs and where the secrets of poetic genius are hidden. Interview.

RFI: You published, a few years ago, the complete works of the Congolese poet Tchicaya U Tam’Si. Tchicaya U Tam’Si: life and work of a cursed man is the new book that you dedicate to this poet. Is this a biography? ?

Boniface Mongo-Mboussa: It is a biographical essay, on the border between essay and biography. We needed narration to tell a little bit about life, but we also needed analysis, to situate the work in context, in time, and to show the place that Tchicaya occupies in the history of contemporary African literature. This is the challenge that I set myself, that I tried to achieve.

These pages are “ an act of gratitude », you write in the preface to your book. What did you mean?

When I was in Africa, in Congo particularly, I had read a few poems taken from anthologies here and there and I rediscovered Tchicaya U Tam’Si in Russia. Everywhere, you were warned: “ Be careful, he’s a hermetic poet “. And there, in Russia, I read it in a foreign language and it is completely transparent. He’s talking to me. And above all, he is a poet who accompanied me during my student period in Russia, which was sometimes painful. Tchicaya was a bit like this big brother who accompanied me. His poetry is the bedside book that I always had with me and sometimes in my pocket, which I read like crazy. He is someone who has been with me ever since.

Tchicaya was born in 1931 in Middle Congo, in what is now Congo-Brazzaville. His father wanted him to study law. How does he come to literature ?

He first came to literature through evenings. He is someone who listened a lot to stories and vigils when he was young and it had a big impact on him. It also comes because Tchicaya had an uncle, who was a scholar, a storyteller, a man who loved to tell poetry in the vernacular, who also translated the Bible into vile. [langue de la famille bantoue parlée en Afrique centrale, NDLR]. These are the two poetic legacies of Tchicaya. And afterwards, he arrived here in France in 1946 in the luggage of his father, a deputy in the National Assembly of the Fourth French Republic.

During his stay in France, the young Tchicaya was nostalgic for his native country. This ” Congo which inhabits it ”, as he liked to say, will be the main theme of his poetry.

Yes, it’s mainly the river. He is a poet from Pointe-Noire. He encounters the river precisely when he is passing through Brazzaville, where the river really resembles an arm of the sea, what we call the ” Stanley Pool ». He is fifteen years old. He is totally dazzled, fascinated by this river. And this aspect is very important in Tchicaya’s poetry, no longer poetry – and I could even say world poetry –, because generally poets are associated with the sea. It is Baudelaire’s verse: “ Free man, always you will cherish the sea ”, or Valéry: “ The sea always starts again “. But Tchicaya, with Holderlin, is a poet of the river, they are fascinated by the river and that is very important.

Bad blood, his first volume of poems appeared in 1955. It is innovative poetry, because it breaks with the poetry of negritude. Why was this break important?

Already, through the itinerary of Tchicaya himself: he is a man who comes from the tale. That is very important, from the vigil and it is someone who did not have the schooling of the poets of negritude who, for their part, are normaliens. So, he’s an autodidact and he’s also someone who, very early on, was rebellious. And so, he poses himself against a poetry, especially that of Senghor which is a poetry of “yes”, which is the poetry of celebration, of elegy. Tchicaya’s poetry is a poetry of “no”. Thematically, he doesn’t want to be a Negro. He finds it too big to assume the status of a Negro on his frail shoulders. He wants to be himself. He wants to be Congolese, he cannot take on the pain of the world while he himself cannot take on his own. And from that moment on, he completely broke with the poetry of negritude.

Tchicaya’s poetry is personal, romantic, but also very politicized, crossed by the poet’s meeting with Lumumba. How did the two men meet? ?

Tchicaya was a journalist, he had friends in Belgium, they talked about Lumumba. Then, there was this famous speech by Lumumba in Brussels which completely shook him up. He then decides to leave everything behind, to follow Lumumba to the Congo. We present him to Lumumba. You should know that in civilian life, his name was Gérald Felix Tchicaya. Tchicaya’s father is called Jean-Félix Tchicaya. So, when Gérald Felix Tchicaya is introduced to Lumumba from Congo-Brazzaville, Lumumba hears Jean-Félix Tchicaya. Why does Lumumba hear Jean-Félix Tchicaya? This is because at the time, Tchicaya’s father was also a deputy in the French National Assembly. He was the most influential politician in Central Africa. And as a result, Lumumba is very reverential towards Tchicaya U Tam’Si whom he takes for his father. For his part, Tchicaya the dunce, the man without a diploma, was treated with equal respect by the most influential politician on the continent at the time. That’s the mistake. The second thing is that Tchicaya will work alongside Lumumba. He will experience three intense months of a political, intellectual, even poetic life. Then, Lumumba dies and everyone must invent another apostolate somewhere. And this apostolate is to magnify the Congo. However, Lumumba himself said: “ The Congo is me. » There is a meeting. You should know that Tchicaya was not the only one at the time to be interested in the Christ-like, charismatic figure of Lumumba. Aimé Césaire himself wrote A season in Congo.

Why are these two poets interested in Lumumba?

Because Lumumba is the only one who said no at the time. He is the one who dared to defy the prohibitions in front of King Leopold II. Delivering this memorable speech is also a way of avenging through words the humiliations and frustrations of the colonial era. So, unlike Césaire, who has a somewhat outsider view, for Tchicaya the relationship with Lumumba is more intimate. Firstly, because he is Congolese like him, because, as I said, the meeting was made on a mistake, but at the same time, it strengthened the links. And this means that when you read, for example, the first collection that Tchicaya dedicates and devotes to Lumumba who is Epitome, you will see that the relationship is very intimate. He identifies completely with him, because he is a poet. He believes he is the voice of the voiceless. He is a journalist: he thinks that somewhere he can also be the witness who will pass on his legacy. And then he is Congolese. And they shared, with Lumumba, this passion for the Congo. Then, he will devote a second collection totally dedicated to Lumumba, which is The belly. Initially, it is a very intimate poetry where the discomfort of the individual dominates, Tchicaya U Tam’Si depicts his guts: he speaks of his club foot, of his difficulty in finding love. These are intimate poems, but the meeting with Lumumba will obviously make his poetry more public, we can even say more engaged somewhere in the good sense of the term, very theatrical. For example, I always thought that a poem like The bellywe can compare it to Shout by Munch, this famous painting by the Norwegian impressionist which is truly a scream. It’s also called The Scream. The stomach is a cry. And there, it’s no longer intimate Tchicaya. It is Tchicaya who cries out his pain in the public square. But even in his fiction, in his second novel called The jellyfish, there is the figure of Lumumba. Finally, in his play The N’dinga Ball, there is the specter of Lumumba which haunts this room. The identification of Tchicaya U Tam’Si with Lumumba is total, because they have a single ambition: the Congo.

Tchicaya has, to his credit, seven collections of poetry, but also, as you have just recalled, novels, plays, The N’dinga Ball is his most famous piece. What does this piece say?

The N’dinga Ball, it is first of all a short story with dialogue, which has become one of the most performed pieces in the African theater repertoire, I would even say in the world. And obviously, this N’dinga Ball comes back to a key moment in the history of Africa where some think that independence is the beginning of a new euphoria, while preparations are already being made somewhere in pharmacies in Europe, in the United States United, the death of this independence. So, it’s a remarkable work, written in the form of a play. The N’dinga Ball remains today the theatrical success of Tchicaya U Tam’Si.

A rebel poet, Tchicaya has been compared to Rimbaud, the “black Rimbaud”. What do you think of this legend, essentially invented by critics?

It’s true. He says it himself. “ I admit to being related to a certain Arthur. » He recognizes it. But I think that if we reduce him to this cliché of “black Rimbaud”, we do not broaden his poetry, because his poetry goes beyond Rimbaud. His poetry is clear. He talks about his discomfort, he talks about his club foot, he talks about love for the Congo, about the death of Lumumba. He is our first modern poet. It is a poetry that juxtaposes the prosaic and the sublime. It is a poetry which has a syntax precisely of juxtaposition. It is a poetry that introduces the story into poetry. But precisely, this is where he innovates, this is where he is modern.

Doesn’t its modernity also consist of having brought the Africa of the forests into the literary imagination? ? “ Tchicaya’s main merit is to have rebalanced African literary geography », there, I quote you, Boniface Mongo-Mboussa.

When you take the manifesto of negritude which is the New anthology of Negro and Malagasy poetry by Senghor, with the preface by Jean-Paul Sartre, you will see that, in fact, there is a great imbalance. Of the sixteen poets it counts, only three are African: Birago Diop, David Diop and Senghor, all Senegalese. And a few years later, Tchicaya arrived and really shattered all the certainties of contemporary African and Negro poetry. From the outset, it rebalances literary geography somewhere, that is to say between the Africa of the Sahel and the Africa of the forest. It was also a Chadian friend, who is a writer himself, who told me that Tchicaya was the poet of the three Fs: fire, rivers and forests. And I think that is very important.

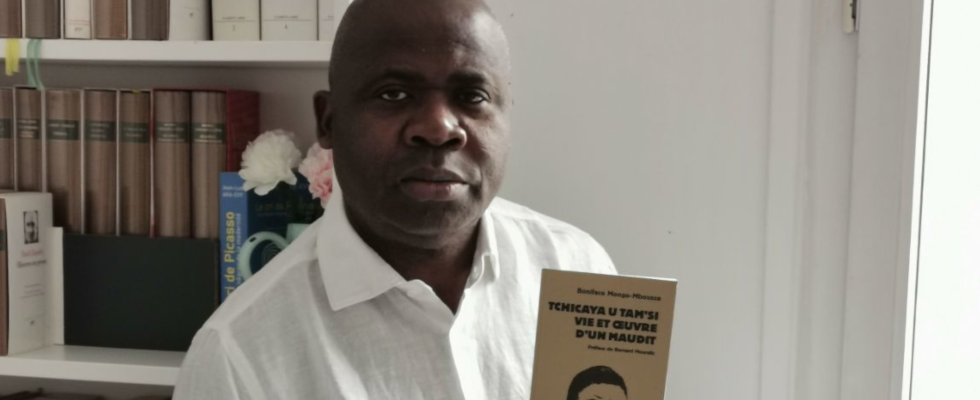

Tchicaya U Tam’Si, life and work of a cursed man, by Boniface Mongo-Mboussa. Preface by Bernard Mouralis. Éditions Riveneuve, 157 pages, 10.50 euros.