Christian Kracht makes these somewhat defeatist remarks in his excellent new novel, Eurotrash : “There was no music or cinema or literature, there was absolutely nothing in Switzerland, except a greed for luxury, a tremendous desire for sushi, garishly colored sneakers, Porsche Cayennes and other DIY hypermarkets in urban areas which were growing excessively.”

No literature in Switzerland, really? Here, lovers of classics will stop at two Genevans who are starting to date, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Germaine de Staël. Readers of Sylvain Tesson will be satisfied with Nicolas Bouvier. The most chauvinistic will point out that the best Swiss writers tend to become naturalized French (Benjamin Constant, Blaise Cendrars, Philippe Jaccottet). As for the Goncourt jury, we will not notice more taste for our neighbors, given that the prize list includes only one Swiss: Jacques Chessex for The Ogre in 1973. Statistics which improve a little on the side of the grand prize of the novel of the French Academy with three Swiss authors on the counter: Albert Cohen in 1968 for Beautiful of the LordJoël Dicker in 2012 for The Truth about the Harry Québert affair and Giuliano da Empoli (Italian-Swiss) in 2022 for The Mage of the Kremlin.

Joël Dicker: the scarecrow’s name is dropped. In certain Parisian circles, it is fashionable to hold one’s nose when one’s surname is pronounced. We make fun of his style, considered heavy, we envy his enormous prints, his ears never stop ringing. We took the time to calmly read Dicker’s new book, A savage animal. Why so much hatred? In the construction of the intrigue and the art of suspense, he demonstrates a mastery from which many snobs who publish with POL or Minuit should draw inspiration. A savage animal tells of a heist in a jewelry store in Geneva, and the consequences it will have on five characters, including a banker who wears a gold Rolex. Certainly, Dicker seems to be concerned about social poverty. The intimate doesn’t interest him anymore. He is not going to look for Edouard Louis on his land. But he has the merit of not being a demagogue, of painting a society that he seems to know well, and he succeeds in making us turn the pages at a rhythm reminiscent of the ticking of the best Swiss watchmaking – no wonder on the part from a man who was an ambassador for the Piaget brand.

Intelligence and melancholy

Although we recognize his qualities, Joël Dicker does not need us. So let’s move on to at least media Christian Kracht. Since the publication of Faserland in 1995, he was considered in his country as a sort of Bret Easton Ellis of the canton of Bern. A priori, Dicker embodies everything he hates. Kracht’s literature follows in the wake of a Swiss compatriot (Fritz Zorn) and an Austrian cousin (Thomas Bernhard). This shows that the mood is one of black humor. Eurotrash depicts the moods of a rich kid who had no reason to complain about his parents’ real estate assets – among other properties, include a villa in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, a chalet in Gstaad and a castle in Morges, on the shores of Lake Geneva. Having a grandfather who was an SS officer in his family tree has darkened the heart of the narrator, who lives with other demons. His father is dead ; his mother, in her eighties, is losing her mind. One morning, our man goes to see her at her house. Madame takes shots of vodka, white wine and painkillers. She is accustomed to being in a psychiatric hospital. Her son offers to take her on a trip and puts her in a taxi. She convinces herself that they are going to Africa, on the trail of zebras. They will never fly. Here they are, going around in circles in Switzerland, remembering often sinister memories, bickering, making nasty jokes at each other; then soften and come closer. This novel in the form of an oratorical joust gains depth throughout the pages, and Kracht is touching with his intelligence and his melancholy, which recall the autobiographical writings of Guy Debord (mentioned several times).

Certain sharp passages ofEurotrash are more gratuitous, such as this one: “I had always hated Geneva, this abominable Protestant city, lying, cold, full of show-offs, boasters and nitpickers. We had nicknamed it Calvingrad.” It is in Geneva that Joël Dicker lives and where he has set up, near rue du Rhône (the local avenue Montaigne), the offices of his own publishing house, Rosie & Wolfe. It is also in Geneva, in the world of banking, that Joseph Incardona had located the intrigue of The Subtraction of Possibilities. This time, he sets sail and crosses the Atlantic. Stella and America takes us to a mystical or superstitious United States (your choice) not seen since Wisdom in the blood by Flannery O’Connor. A young prostitute, Stella Thibodeaux, performs miracles contrary to Christian morality: anyone who sleeps with her no longer suffers from her defects and illnesses. Could this woman be a saint? An American cardinal relays the information to the Pope, who does not see it that way: on the contrary, he sees in her a witch who must be exterminated with the greatest discretion. The Vatican dispatches two hitmen, the Bronski brothers, to eliminate this annoying devil. It means counting without a journalist and especially Father Brown, a former elite military priest: they come to the aid of the sinner benefactor. Will she save her skin? This bouncy and surprising comedy makes us think of an ideal addition between A private in Babylon by Richard Brautigan, the Boris Vian period Vernon Sullivan, certain films by the Coen brothers and Monsignor by Jack-Alain Léger. Bigots refrain…

Spiritual and sensual faux thriller

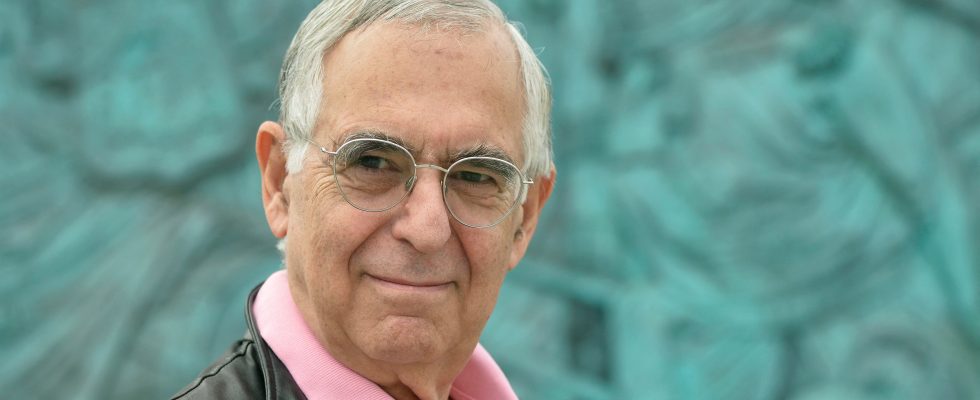

Said bigots should also be shocked by Metin Arditi’s new book. In the previous one, already, The Bastard of Nazareth, he started from the hypothesis that Jesus would be the son of a Roman soldier – he saw in this childhood wound the psychological spring of Jesus’ life, the source of his hatred of the Pharisees and his desire to reform Judaism . With The French Island, Arditi leaves the Holy Land for Greece, in this case the imaginary island of Saint-Spyridon. There we find a convent of nuns where corporal punishment is still taking place when the book opens, in 1950. Clio takes the veil. Problem: she was introduced to photography by a French woman, Odile. As Clio begins photographing her nun sisters in suggestive poses, Odile’s only daughter disappears. Are the two events linked? We fall into a imitation thriller that is singular to say the least, both spiritual and sensual… Born in Ankara in 1945, naturalized Swiss in 1968, Arditi is a rare bird, at the crossroads of several cultures. Of the authors cited in the preamble, he is perhaps closest to Albert Cohen. When reading The French Island, we say to ourselves that it is a shame that Michel Déon is no longer in this world: this novel was made for him. We hope that many readers will take up the torch. In genres that could not be more different, Christian Kracht, Joseph Incardona and Metin Arditi show that there remains a living literature in Switzerland today. Better to read these three than to get carried away by a tremendous desire for sushi, garishly colored sneakers and Porsche Cayennes.

A savage animal, by Joel Dicker. Rosie & Wolfe, 398 p., €23. Eurotrash, by Christian Kracht, trans. from German (Switzerland) by Corinna Gepner. Denoël, 186 p., €20. Stella and Americaby Joseph Incardona, Finitude, 214 p., €21. The French Islandby Metin Arditi, Grasset, 229 p., €20.

.