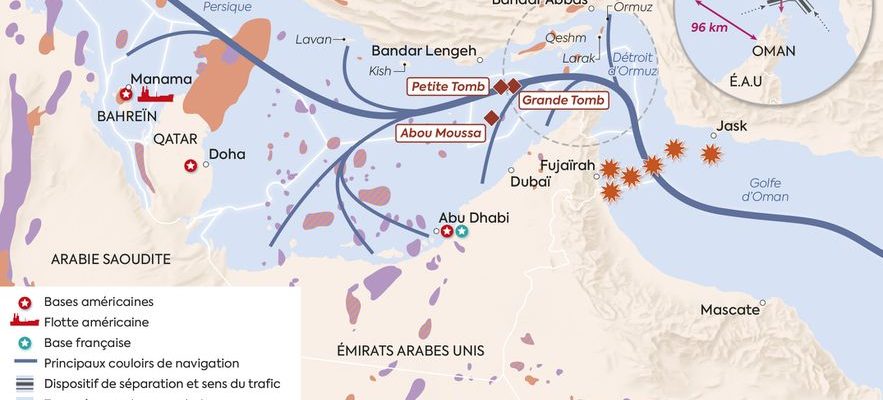

“It’s the place in the world where everyone listens to everyone”, summarizes Jean Rolin, journalist and author of the novel. Hormuz (POL, 2013). On this strip of sea located between Iran and Oman, some forty kilometers wide, of which only 3.5 are navigable, thousands of boats circulate: one must imagine, as Jean Rolin describes The Express, these immense oil tankers emerging from the sea mist, not leaving the narrow navigation rail between the island of Hormuz and the peninsula of Musandam, an exclave of the Sultanate of Oman. Alongside them are patrolling warships, notably American and French, container ships carrying a bric-a-brac of goods from China bound for Arab countries. We also come across hundreds of dhows, these small sailing boats that engage in smuggling with more or less impunity, especially at dusk when, like swarms of flying fish, they pass from one bank to the other, clumsily hiding their cargo under tarpaulins. In this marine traffic jam the small motorboats of the Pasdaran, the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, swirl. These paramilitaries of the Tehran regime come too close to merchant convoys, carry out intimidation maneuvers, challenge certain vessels and ignore others, without our always being able to detect any logic in this. This strange carousel well known to those who use the strait, one of the busiest in the world, is it more than a masquerade intended to convince that at the edge of the Persian Gulf the Iranians reign supreme over the waters?

When, with each diplomatic crisis, Iran finds itself in a weak position, the Guardians threaten to block the passage. And, therefore, a large part of the world’s oil production: Kuwait, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Oman transit 90% of their production there, i.e. 20% of world crude, according to OECD figures. In recent weeks, the incidents have resumed, while, at the same time, the Iranians confirmed in mid-June that an indirect negotiation channel had been established with the United States. The West wants guarantees on the Iranian nuclear program, and Tehran aspires to soften the sanctions, while the country’s economy is suffocated and the regime has been facing a popular protest movement since last September.

At the beginning of July, the American navy had to intervene to prevent the seizure by Iran of two oil tankers in international waters, off the coast of Oman. By May, the Guardians had arrested two. Each incident awakens the memory of the intense tanker war, which saw Iran and Iraq oppose each other from 1984 to 1987. At the time, the Iraqi air force bombed Iranian tankers. The Islamic Republic will go so far as to lay mines on the navigable route. More recently, from 2018 to 2021, in the wake of the American withdrawal from the JCPOA (multi-party Iranian nuclear agreement, which provided for the lifting of sanctions against the regime in exchange for strict control of the atomic program), several attacks affecting tankers, orchestrated by the Tehran regime, have seriously disrupted traffic. Without ever stopping it completely, despite thundering declarations.

3760_3761 ORMU card

© / legends and cartography

“The strait is not so easy to block”, tempers Jean Rolin, who has traveled it on various boats and at different times. “There is no place where you can see both shores. It is not by sinking a simple ship that you could block it. On the other hand, you can undermine it and disrupt traffic a lot, making it impracticable”, he concedes. Where the Iranians have real means of pressure is that the alternatives are not legion. “No infrastructure or pipeline allows for a flow comparable to that of all the tankers passing through this space”, summarizes Kevan Gafaïti, doctoral researcher at the Thucydide center in Panthéon-Assas and author of The Strait of Hormuz Crisis from 2018 to the present day (Harmattan, 2022). Among these possibilities, the East-West pipeline, also called Petroline, crosses Saudi Arabia. But it is poorly protected, and its capacity does not exceed 5 million barrels per day. Against 20 million at the height of traffic by sea. For their part, the Emirates are trying to make the port of Fudjayra a credible option, but it remains very exposed to attacks.

A bullying strategy

Despite their bluster, it remains unlikely that the Guardians will ever block the strait. But even if they can’t really close it, this is the place where they can express their maximum nuisance force. Kasra Aarabi, director of the Iran program at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, assures that this area is essential in the strategy of the paramilitary organization. “It comes from their worldview: Since 2018, they have detained and boarded multiple commercial vessels, and done so with impunity. The Guardians are therefore not afraid of the consequences.” This great specialist in the Revolutionary Guards points to the role of a central figure, Ali Akbar Ahmadian, a sixty-something general appointed last May to head the Supreme National Security Council in Iran, the country’s highest security body, which defines defense and security strategies. At the heart of this system is the strait. “Ali Ahmadian is one of those who precisely defined this strategy of asymmetric attack against American forces in the Persian Gulf. He is convinced that this way of doing things, namely the harassment of ships, works.”

At the center of this naval battle are three islands claimed and occupied since 1971 by Iran and recently returned to the fore: Abou Moussa, Grande Tumb and Petite Tumb. Following a meeting of the Gulf Cooperation Council in early July, the Emirates recalled their aims on these three stones. But what is the point of claiming them? “By controlling these islands, you are master of the only two navigation corridors, specifies Kevan Gafaïti. It is also there that Iran will keep most of its arsenal, miniature submarines which can accommodate crews of 5 or 6 soldiers, and the famous small speedboats equipped with machine guns with which the pasdaran patrol. “

In the area, “the Iranian authorities tell you clearly that there are places where it is better not to look”, laughs Jean Rolin. But if it is difficult to assess the importance of Iranian forces in the area, the heavy artillery is out. The United States stands in particular their fifth fleet in Bahrain. More than military, the game is above all diplomatic. “The Revolutionary Guards behave like a terrorist organization, including in the strait, insists Kasra Aarabi. As long as they are not arrested, they will continue their methods: taking hostages, boardings, harassment, everything that can serve their objectives. “