It is called “the least rare of rare diseases”. Sickle cell disease, to which a world day is dedicated this Monday, June 19, has become a growing public health issue in France, the first country affected in Europe. And for good reason: it concerns between 19,800 and 32,400 people, according to a study based on data from Health Insurance. A number of patients which tends to increase, with 400 newborns diagnosed each year, an increase of more than half between 2010 and 2020.

Appearing in Africa and India, sickle cell disease has established itself in America, particularly in the West Indies and Brazil, as well as in Western Europe due to population movements. “Carriers of the gene represent approximately 20 to 25% of the population on the African continent. It is linked to their genetic heritage”, explains to L’Express Professor Jean-Benoît Arlet, internist at the European hospital Georges- Pompidou (AP-HP) and specialist in this disease. In France, 55% of sickle cell sufferers are born in Ile-de-France and 15% in the overseas departments and territories. “I don’t know of other diseases that are so concentrated in one area, but that is changing,” says the specialist. Worldwide, it is one of the most widespread genetic diseases, with 300,000 births.

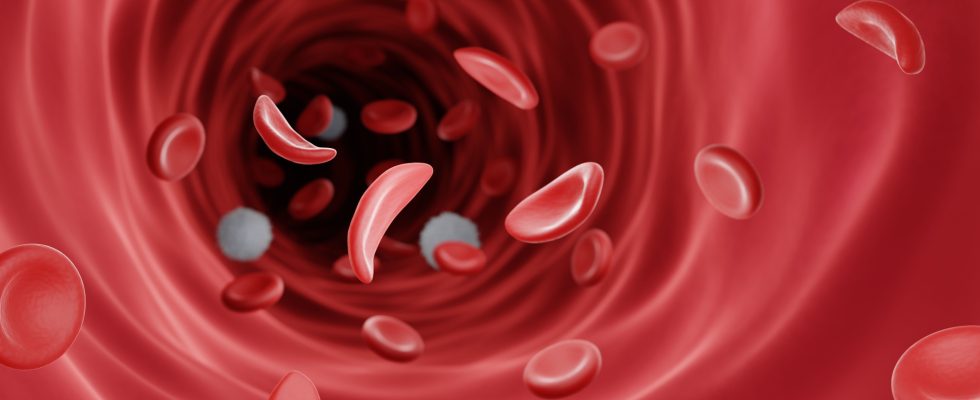

Unknown to the general public, this hereditary disease is transmitted by both parents carrying the gene but not sick. “When two carriers are together, they will have a risk in four of having a baby with sickle cell disease,” comments Jean-Benoît Arlet. Sickle cell disease affects hemoglobin, the main protein of red blood cells and causes their deformations. Consequently, they lose their rounded shape and take on the appearance of a sickle (drepanos = sickle in Greek). The symptoms of the disease are variable and depend not only on age, but also on the severity of the disease. Jumble: chronic anemia, acute painful crises, increased risk of infections. “They have intense bone pain and when it exceeds an intolerable threshold, they have to go to the emergency room to be relieved by morphine and often be hospitalized for a few days”, continues the professor.

A life expectancy of around 55-60 years

The various complications linked to the disease are likely to affect vital organs, such as the kidney, the osteoarticular system, the liver or even the lungs. “The small vessels become clogged and this will lead to chronic complications on the organs which will be responsible for half of the deaths in sickle cell patients”, continues Sylvain Le Jeune, head of the internal and vascular medicine unit of the Avicenne Hospital in Bobigny (AP-HP) and coordinator of a reference center for sickle cell disease.

Over the decades, treatments have increased life expectancy, which is now around 55-60 years in France. By way of comparison, it was less than 20 years before the 1980s. An evolution which is not homogeneous in the world. “In Africa, 50% of children under the age of 8 affected by the disease die from it,” says Professor Jean-Benoît Arlet. The specialist regrets that the continent does not have access to hydroxyurea-based drugs, widely used in France from the 2000s. They make it possible to reduce the consequences of sickle cell disease and, in the long term, to “protect the organs “. These drugs are used from an early age.

“Gene therapy is a great hope, but we are not there yet”

In current tools, blood transfusions must be done regularly, but can have significant side effects. For now, the only hope for a cure is bone marrow transplantation, which is still too rare. A procedure that requires a compatible donor, often a brother or sister. “Only 18 to 20% of sickle cell patients have this possibility”, specifies Sylvain Le Jeune. Heavy and expensive, it is reserved for the most severe forms of the disease, especially in children. In France, about twenty patients benefit from such a transplant each year. “In my center, there is a transplant every two months while we follow 600 patients. However, the results are satisfactory since it allows the healing of 85% of adults and 98% in children”, testifies the Pr Jean-Benoit Arlet.

For those who could not access a transplant, gene therapy has been at the center of several clinical trials in recent years in France. In November 2022, a team of scientists from Inserm, the University of Paris-Cité and the AP-HP within the Imagine Institute, has shown the effectiveness of a gene therapy approach. The goal is to insert a normal gene into cells with a faulty gene so that it does the job that the mutated gene does not: make healthy red blood cells. “Gene therapy is a great hope, but we are not there yet”, attests Sylvain Le Jeune.

Generalize birth screening

In the meantime, birth screening remains a crucial tool to limit complications. Only downside: it is still very uneven. Indeed, it only concerns children born in the overseas departments and regions. In mainland France, it is offered to those with parents from more “at risk” regions of the world (in particular Africa, the Middle East, the Indian Ocean and the West Indies). From one region to another, this targeted screening is heterogeneous, “while no region is free of cases”, according to the High Authority for Health (HAS), in a opinion delivered on November 15, 2022. After concluding, during its last assessment in 2014, that it was not “necessary”, the HAS recommends generalizing it to all newborns. “More than three out of four children benefit from it in Ile-de-France, compared to barely one out of two nationally in 2020, while no region in France is free of cases”, points out the press release from the HAS.

In addition, some cases would fall through the cracks, resulting in a high loss of chance for the patients concerned. “A study has shown that if we only did targeted screening, we missed 7.5% of children with sickle cell disease diagnosed by systematic screening. Every year, a few deaths occur in children who were not screened in time. Prevention is all the more important as there are no symptoms in babies under 18 months,” insists Sylvain Le Jeune.

But, announced from January 2023, expanded screening does not yet apply in the field, deplore some associations, awaiting a ministerial text. For his part, the Minister of Health and Prevention promised in a press release to organize, “from the coming months, the preparatory work for the concrete implementation of this” systematic screening, “as soon as possible”. While the decree providing for generalized screening from birth is long overdue, patient associations will submit, this Monday, June 19, to the Minister Delegate Agnès Firmin Le Bodo, a white paper to fight against sickle cell disease.