Usually, when the head of government has an absolute majority, the budget vote in Parliament seems like a walk in the park. During the last two elections, Élisabeth Borne could only count on a relative majority: the pace was therefore more sustained, to the martial sound of Article 49.3. This time, it is a 110-meter hurdles that is announced. With a headwind, without warm-up, and in a generally hostile stadium, regardless of the bib of the person who will carry the text.

By October 1 at the latest, the executive must submit to Parliament, which will open its ordinary session on that date, a draft finance bill (PLF) for 2025. But before even discussing these budgetary guidelines, the deputies are required to vote on another draft law, the one relating to the results of management and approving the accounts for 2023, tabled by the previous government in July 2024. Basically, sign the exit inventory.

The outcome of this “vote” is irrelevant, it only needs to take place to allow the process to continue. The more time passes, the more this banal step risks becoming complicated to organize. “The President of the Republic can call an extraordinary session of Parliament in September to allow the deputies to vote on this accounting text, even if it is defended by the resigning government,” Aurélien Baudu and Xavier Cabannes, professors of public law at the University of Lille and Paris Cité, explained to L’Express. With one question: “Does defending one’s record fall under ‘current affairs’?”

By October 1 at the latest, the executive must submit to Parliament, which will open its ordinary session on that date, a draft finance law (PLF) for 2025.

© / The Express

To raise the tax, the agreement of Parliament is essential

Once the first obstacle has been overcome, the next ones will not be lacking. This PLF may well be announced as a rump text, purged of any expenditure with political connotations to avoid a coagulation of oppositions, it remains essential to the functioning of the country. And for good reason: it is through it that the executive receives the authorization of the representatives of the people to collect taxes. “We have somewhat forgotten it, but in 1789, we made the Revolution for that,” recalls Martin Collet, professor of public law at the Panthéon-Assas University. Consent to taxation is an essential element of our democracy, enshrined in Article 14 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The government cannot do without parliamentary agreement here.”

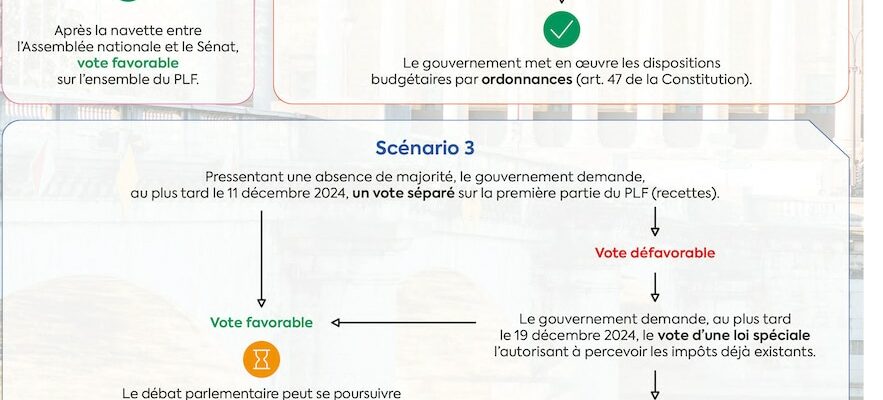

Unless the shuttle between the Assembly and the Senate drags on and exceeds 70 days. In this case, the executive takes back control and, by authority, implements the PLF by ordinances. “We can imagine a blockage in the joint committee, bringing together the parliamentary protagonists of the text, and a bogging down of the debates. Since 1959, there have already been times when this deadline has been exceeded by one or two days, but the government has never used the option offered by Article 47 of the Constitution, point out Aurélien Baudu and Xavier Cabannes. Let us also not forget that the Constitutional Council must be given a reasonable period of time to rule on the text at the end of the year… Parliament would have no interest in depriving itself of its budgetary competence.”

The government’s two jokers

To obtain the approval of the national representation on the essential question of taxes, the government has two cards up its sleeve: request a separate vote on the first part of the PLF – revenues – or, failing agreement from the deputies on this point, return to the charge by putting to the vote a special finance law that authorizes it to raise existing taxes. The maneuver would have the advantage of postponing the examination of the second part of the PLF, the most stinging, that dedicated to expenses. It would also allow the Prime Minister to sign decrees of “voted services”, i.e. the minimum credits that the government deems essential to continue the execution of public services – such as paying civil servants’ salaries – under the conditions approved the previous year by the two chambers.

“Is it in the interest of Parliament to go so far as to deprive the State of any means of action?”, ask Aurélien Baudu and Xavier Cabannes. Especially since the finance law, they point out, also sets and stops the operating credits… of the Palais Bourbon. If it were to happen, this double blockage, unprecedented under the Fifth Republic, would lead the country into an impasse. “Rejecting the budget would have the equivalent effect of voting on a motion of censure,” the two specialists believe. With the immediate consequence of the resignation of the government. A fiscal chaos coupled with an institutional crisis. A disastrous cocktail.

Article 16, the object of fantasies

The worst being “not always certain”, as Paul Claudel wrote, some jurists have mentioned in recent days the possible recourse by the President of the Republic to Article 16 of the Constitution which gives him “exceptional powers” in the event of serious and immediate threats to “the institutions of the Republic, the independence of the nation, the integrity of its territory or the execution of its international commitments.”

A hypothesis dismissed by Denys de Béchillon, professor of public law at the University of Pau and columnist at L’Express: “We speak too lightly of Article 16. First, it is not designed to respond to a budgetary hiccup but to a coup d’état or a war. Then, before it can be implemented, it must be the subject of an opinion from the Constitutional Council, immediately made public, which would then have colossal political magnitude. If the Sages said no to the president, the latter would very seriously expose himself to impeachment.” His colleague Martin Collet agrees: “The Constitutional Council would make a fool of itself if it admitted that the president could go through this to have a simple budget adopted. The flexibility of the Council and its sense of the State are well known. But in this case, this position would be really difficult to maintain…”

A 49.3 emptied of its substance

The legislative route therefore remains the only one that is worthwhile for France to equip itself with a finance law. With one last handicap, one more, compared to the usual procedures: the use of article 49.3 of the Constitution is now emptied of its substance. Thanks to it, the Prime Minister can pass a text without a vote by engaging the responsibility of his government. “In normal times, it is a useful mechanism for welding together a heterogeneous parliamentary coalition, explains Denys de Béchillon. Because there is a downside: in the event of a motion of censure, the Assembly can be dissolved by the President of the Republic, which forces the deputies to think twice since they take the risk of having to go back before the voters.”

Not this time. Emmanuel Macron having blown his cartridge, the censors have the red carpet: no new dissolution being possible before a year, that is to say in June 2025, they would be assured of not losing their seat if they felt like bringing down the government this autumn. A budget of all dangers: rarely has a hackneyed formula rung so true.

.