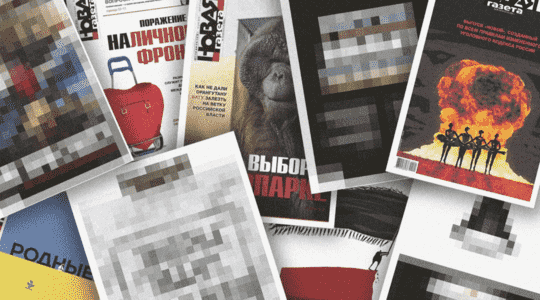

The prestigious Nobel Peace Prize awarded to its editor was not enough to protect the independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta. Faced with the Kremlin’s crackdown on the dissonant voices rising as Russia wages war on Ukraine, the newspaper took a heavy decision on Monday, March 28: to suspend publication until the end of the intervention in the neighboring country. It was the last bastion of the free and independent press in Russia.

“There is no other way. For us, and I know for you, this is a terrible and painful decision. But we must protect each other,” the editor wrote. in chief Dmitry Muratov, in a letter addressed to the readers of the newspaper. Novaya Gazeta announced that it had decided to suspend its publications on its site, on social networks and in paper format after receiving a second warning from the telecoms policeman, Roskomnadzor, for breaching a controversial law on “foreign agents”. According to the Nobel Prize, its editorial staff continued its work for 34 days “under the conditions of military censorship”, since the launch of the Russian offensive on February 24.

A pillar of investigative journalism

Pillar of investigative journalism, Novaya Gazeta has been publishing investigations into corruption and human rights abuses in Russia for almost 30 years. In 2021, this work, which cost the lives of several of its reporters, earned its editor, Dmitry Muratov, the Nobel Peace Prize. This award and the international aura of Novaya Gazeta seemed so far to have relatively preserved the pressures. But since the beginning of the Russian offensive in Ukraine, the authorities are still tightening their grip around the last independent media in the country.

He says his reporters have covered combat zones in Ukraine and estimated the extent of “losses and destruction”. “We tried to understand how our people allowed two wars to be waged at once: one, of conquest, in Ukraine, and another, almost civil, at home, in Russia.” On March 22, the journalist announced that he was selling his Nobel Prize medal for the benefit of Ukrainian refugees.

Founded in 1993, the newspaper Novaya Gazeta enjoys a high reputation for its investigations into corruption and human rights abuses, particularly in Chechnya. This commitment cost the lives of six of her collaborators, including the famous journalist Anna Politkovskaïa, assassinated in 2006. She was one of the rare Russian journalists to denounce human rights violations in Chechnya, and to openly criticize the abuses of the regime. of Vladimir Putin. “At least 80% of the information we publish is not treated by any other newspaper, underlined to L’Express Sergei Sokolov in 2009, the deputy editor at the time. We would like to write on other themes but the number people who turn to Novaya Gazeta to denounce an injustice is so high that our journalistic commitment ends up being confused with a fight for human rights.” By dipping their pen in the wounds of Russia, the journalists of Novaya Gazeta know that they are risking their necks at all times. And that they work without a net or protection.

Respected, Novaya Gazeta nevertheless remains relatively marginal in Russia. In February 2022, its single-issue circulation was around 100,000 copies, while the completely free site claimed 40 million visits in the same month.

A heavy repression

Specifically, it is blamed on Novaya Gazeta for not specifying that an NGO mentioned in one of its articles was qualified as a “foreign agent” by the Russian authorities, as required by law. The newspaper received a first warning on March 22, then a second on March 28. Since the start of the military operation, the sites of many Russian and foreign media have been blocked in Russia.

In March, the authorities also passed several laws punishing heavy prison sentences for what they consider to be “false information” about the conflict. The “foreign agents” law is another weapon used against organizations or individuals critical of the Kremlin. Those who are described as “foreign agent” are required to present themselves as such in each of their publications, including on social networks. And the media that mention them must also specify this each time.

The terms of the law are intentionally vague: almost everyone can thus be targeted and fall into the category of “foreign agent” according to the goodwill of the Russian authorities. This is the case, among others, of Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the detainees’ aid association OVD-Info as well as certain independent media such as TV Rain or Meduza. Prosecutions for breach of this law can have serious consequences. In December, Russia’s most respected NGO, Memorial, which was branded a “foreign agent”, was banned for failing to state that status in certain publications.

The head of European diplomacy Josep Borrell on Monday criticized the “systematic repression” which targets independent media in Russia, while Moscow has tightened reprisals against independent entities since the start of the conflict. Russia is implementing “censorship that comes with manipulation and disinformation” to control the narrative of the conflict in Ukraine that reaches Russian public opinion, he said in a statement.

On Twitter, the NGO Reporters Without Borders reacted by calling on the authorities to end their “censorship policies”.