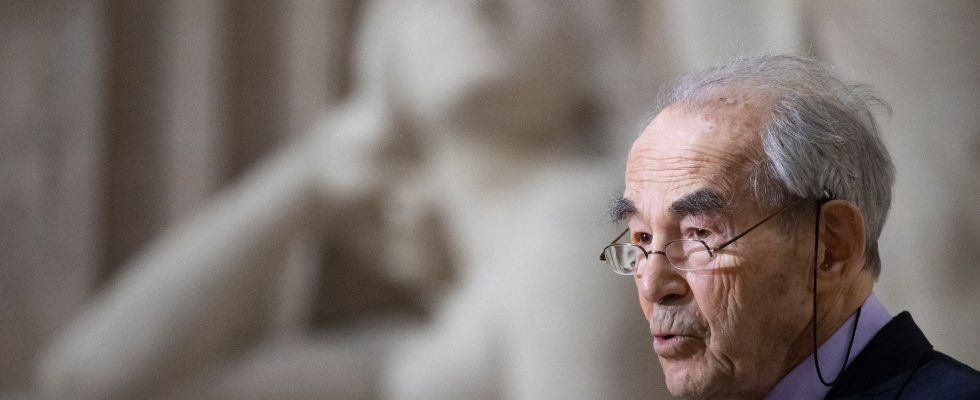

A “hard worker”, who saw “the full potential” of the people he worked with. Jean-Louis Nadal, former magistrate, ex-president of the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life and Attorney General of the Court of Cassation, is inexhaustible on Robert Badinter. An architect of the abolition of the death penalty, former Minister of Justice emblematic of the Fifth Republic, the lawyer died on the night of February 8 to 9. His voice tight with emotion, the man who was his technical advisor at the Chancellery from 1983 to 1985, tells us about “his” Robert Badinter.

L’Express: How would you describe Robert Badinter?

Jean-Louis Nadal: On a human level, he is extraordinary. In terms of justice, he is a giant of justice. He is a man who took his responsibilities with conviction and was a tireless worker. A hard worker, demanding, rigorous, human. He was a man who knew how to listen and feel. Through the responsibilities he entrusted to me, I was able to attest that he left his mark on the history of the legal world.

He knew how to establish a working method. A methodology of responsibilities. He knew how to motivate, coordinate and evaluate. He commanded respect, everywhere, whatever the sensitivities of each person. He had a sense of justice, which shone through, not only through his words, but also through his actions, his decisions. He was a man of action, who knew how to seed the judiciary of tomorrow. At the National School of the Judiciary, he brought pedagogy, an opening of the institution to society, to major public decision-makers… He gave breathing room and responsibility. When you meet a man of this dimension, there is a bond other than friendship that is formed, there is affection. He was someone sensitive, very attentive to others, always, always, always knowing how to listen. Working with him was a pleasure.

The general public knows him above all for his fight for the abolition of the death penalty. But you insist on his “substantial” work within the judicial institution…

He was the man responsible for the recovery of the institution. When he arrived at Place Vendôme, there were considerable delays. I remember traveling alongside him to the Montpellier Court of Appeal, or to the Social Chamber, where we heard at four or five years old. For him, this was unacceptable. To use an expression that was familiar to him when he was not happy with certain things in the courts, he said to me: “Nadal, you have to take matters into your own hands! Look what’s happening there. I’m drunk with rage!”

He was a man of contact. Place Vendôme? Of course ! But he told me: “The moment of truth, Nadal, is the court. It’s there, and we’re going there!”. We have worked in all the courts of appeal. Our movements were constant. He was an educator. We brought together the magistrates function by function and he took stock of the difficulties and issues.

Robert Badinter innovated while respecting tradition. He succeeded in removing the surplus of uselessness so that justice goes to the essentials. He had an eye on its operations everywhere: the penitentiary, the judicial protection of youth, the judiciary… In all the jurisdictions he passed through – and god we crossed them! – he was everywhere attentive to what could be lights. He saw the potential in people. Each time we left the jurisdiction, already on the train, we took stock. He saw the heart of where we had to go: what we had to reduce, what we had to do. He was a magician. A conductor of justice.

How did you meet him?

I had been chosen by Robert Badinter for my knowledge of all the young magistracy. I had been a member of the ENM management team [NDLR, Ecole de la magistrature] alongside magistrate Pierre Truche. At the time, I was in the judicial services inspectorate and I then went to join him. He had managed to put together an extraordinary cabinet. A united team, a pack. He was at the heart of the reactor of action, at the head of a cabinet of great creativity. Afterwards, I kept in permanent contact with him. When you have worked with a man of such human stature, you cannot cut ties. He followed me throughout my career and was always very good and attentive. He is a great believer who has always been by my side. I knew all the Ministers of Justice. I served him. What a magnificent adventure! It’s an experience that can only mark you forever, thanks to him. The man scores.

You mention the ENM. What was Robert Badinter’s influence on the school?

He supported his action. He had this terrible strength: with him, everything went through ethics. It was his backbone. He was a man of total exemplary character. My professional life has allowed me to see the mysteries of the Republic. Often, in my actions, in the positions I have held, I have been able to measure the importance of this righteousness, and of his work ethic. I still see him, today, telling the listeners of Justice, in the large amphitheater of the ENM: “The rule of law, dear listeners, is everyone’s business!” He put this advice into practice and worked with everyone: lawyers, customs officers, police officers… He was the man who brought an essential dimension to the magistrates: he knew how to lead a policy. He knew how to distinguish between what is a judicial policy set in motion by the government, and the politics of setting judicial policy in motion. He was very methodological. For example, we have put in place procedural contracts. When procedural times had reached four or five years, we managed to reduce them to 18 months!

With his methodology, he elevated the greatness of the magistrate not only to the rank of technician of knowledge, but of know-how, of responsibility. This profession is an inexhaustible source of wealth. He said it, while showing the difficulty linked to his functions. That justice is an act of violence. You have to take responsibility. He embodied and he wanted justice to embody. He succeeded in this area: competence, responsibility, courage, and independence, which he had built into his body. All of this was exceptional. He was a god. It was Robert Badinter.

You were in the cabinet after his fight for the abolition of the death penalty. Did you still feel the stirrings of this battle when you arrived?

He had enemies. He was a target. But if you want, his dimension, his charisma, his way of being… Despite all the opposition, he ended up becoming consensual. This he owed to his ability to transcend divisions. I have a vivid memory, where we were returning from a trip to an important prosecutor’s office. At the time, we were not on a TGV – we were rather frequenting the Corail trains – and we were talking about the public prosecutor in question, who had the reputation of being supposedly rather right-wing. I see him, still today, in front of me, separated by the tablet. He told me: “Nadal! We’re making him a PG. A public prosecutor. He’s loyal, he has the sense of state.” Whatever the label. Badinter knew how to put things into perspective.

He also owed this general approval to his ability to make decisions. This man knew how to decide, but always after consulting and listening deeply. When we chose to take Pierre Truche as prosecutor general for the trial of Klaus Barbie, I experienced one of the most moving moments of my career. At that time, we had put in place a method in the management of the judiciary. A magistrate had to remain in office for a specific time before changing position. When the Barbie affair happened, Pierre Truche, whose right-hand man I was at the ENM, did not have the time necessary to change positions. But he was a magistrate with a formidable human, educational and charismatic dimension. I remember that Badinter said “In great circumstances, great men. It will be Pierre Truche. No offense to anyone.” And it was extraordinary. Badinter had a deep admiration for Truche.

How do you perceive Robert Badinter’s legacy today?

Humility, which he embodied; wisdom, which he exuded; the love of justice, which transfixed him, should allow us to look today at what he did, how he did it and why he succeeded. By drawing on the work of Robert Badinter, we should certainly find the real remedies so that the judicial institution truly finds its true place at the heart of the Republic. We must dig into everything he did, in this spirit of quality and respect to perhaps find the paths so that Justice can find those that he had traced: a Justice respected, everywhere, recognized, independent. This passion for Justice, which, I am sure, carried him until his last breath, commanded respect.

From the situation we found, until his departure from the Constitutional Council, he had not left any of the objectives we had set aside. He left for the Constitutional Council having established new foundations and a functioning of the judicial institution which commanded respect. He had accomplished his task. Today, given developments, he would take things differently, I think. The last time I saw him, we talked about what he considered to be the crisis of the institution. He was very worried and concerned in particular about a weakening of the rule of law in the country, as well as the sense of probity and the exemplary nature of public officials.

.