This April 25, Portugal commemorates the fifty years of the military coup which overthrew the longest dictatorship that Europe knew in the 20th century. Some resistance fighters who “ risk everything to improve your life and that of others » told us what the fight against the dictatorship was like, the tortures, the prisons, the escapes, the clandestinity and the exile until the “Carnation Revolution”.

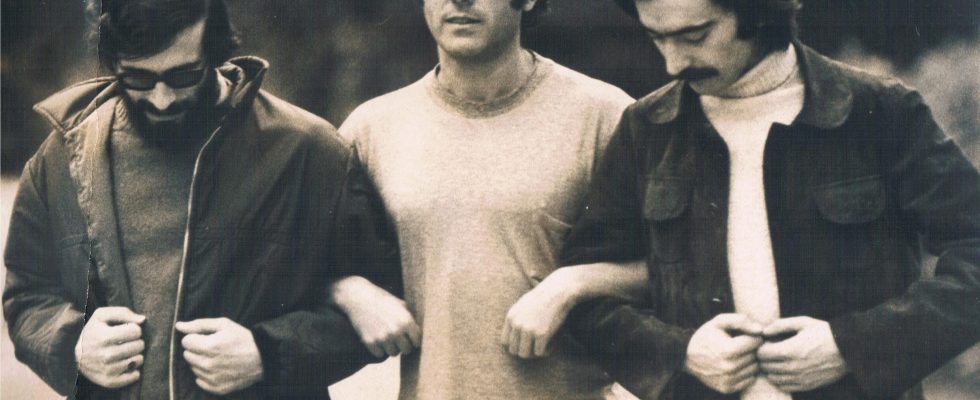

On April 25, 1974, at twenty past midnight, the song Grandola Vila Morena, by José Afonso, is broadcast on the radio and it is the signal that the military was waiting for to trigger the coup d’état which would overthrow, in 24 hours, a 48-year-old dictatorship. A few years before, in 1971, the song was recorded at the Château d’Hérouville, in the Paris region, for the album Cantigas do Maioby José Afonso, the master of Portuguese committed song, with José Mário Branco, the musical director of the record, Carlos Correia, the guitarist, and Francisco Fanhais, another musician friend.

Known as “the Fanhais priest”, the latter was forced into exile after being forbidden to sing, give lessons and hold masses at the Portugal because of his positions, particularly against the colonial war. In France, he joined LUAR, an organization of armed struggle against the Portuguese regime, and he continued to sing to Portuguese émigrés for, he says, “ awaken in them a political dimension and open their eyes to what was happening in Portugal because many wanted to forget the life of suffering that they had left “.

More than 50 years later, Francisco Fanhais does not hide the pride of having participated in the recording of the song which became the symbol of the “Carnation Revolution”. The music begins simply with the sound of footsteps on gravel which inevitably refers to the military march towards the fall of the dictatorship.

“ I have no credit for the military choosing this song, but I am happy and I have a certain pride in knowing that my steps are in this music and that my voice is there too, as well as that of my friends. Every time I hear it, many things come back to me and I remember the force with which we sang, the force we gave to “Grândola”, to the sound, to the steps. I can’t help but feel this joy of knowing that the steps we recorded were a musical and cultural contribution to ushering in the most important thing, namely, the overthrow of fascism. »

In the RFI archivesPortugal: the communist legacy of the Carnation Revolution

Torture, marriage behind bars and escape from prison with the dictator’s car

Domingos Abrantes and Conceição Matos were also in exile for just a few monthsin Paris, on April 25, 1974, after years, either behind bars or “ to flee the police or prison“, because of their role in the main opposition party then banned, the Portuguese Communist Party. They returned to Lisbon, five days after April 25, with the leader of the party, Álvaro Cunhal, on an Air France flight which remained known as ” freedom plane “.

“ It was an Air France flight with lots of exiles returning to Portugal. We were lucky to have been chosen to accompany Álvaro Cunhal. It was an immense joy. The musicians Luís Cília, José Mário Branco, the whole plane sang revolutionary songs! “,remembers Domingos Abrantes, 88, emphasizing that “the conquest of freedom is something that changed the Portuguese people “.

Freedom came after 48 years of oppression and clandestine struggles by people “ able to risk everything to improve their lives and those of others», adds the former resistance fighter. An activist in the Portuguese Communist Party since 1954 and a member of its central committee from 1963, Domingos Abrantes was a political prisoner between 1959 and 1961, then between 1965 and 1973. He even got married in Peniche prison, near Lisbon. , and participated in one of the most spectacular collective escapes from the prisons of the Portuguese dictatorship in December 1961. He and seven communist comrades broke down part of the main gate of the Caxias prison aboard an armored car which had been in the service of the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar.

“ It’s a film story. Escape in a prison car, in a prison that is closed, that has gates. This escape became historic. It was the last collective escape from fascism. This is a politically motivated escape, carried out from a private prison of the PIDE, the political police, and using a Salazar armored vehicle. It is said that Salazar never wanted to set foot in the car again, because the car had been dirtied by communists! »

The escape was “prepared for 19 months and it only lasted 60 seconds! », he adds. It was an inmate mechanic, who had won the trust of the guards, who took the wheel, while a dozen prisoners played football during “recess”. Everything under the eyes of the guards and under a hail of bullets, but the vehicle was armored, “ a monster, almost a tank, a 3,000 kilo car or something like that», Adds Domingos.

Four years later, the police found him and he suffered the torture of sleep and the statue for a fortnight, electric shocks and many blows, because“the only way to keep someone from sleeping is by kicking the knees, hitting the shins, punching the head, making noise“, he said. A month followed in total isolation in “a hole“, a tiny cell “where neither sound nor light came“.“I know what it’s like to be buried alive”he summarizes.

Conceição Matos has also become a symbol of resistance, to the point that the musician José Afonso wrote a song for him – “Na Rua António Maria” – in reference to the interrogations suffered in the terrible headquarters of the political police on Rue António Maria Cardoso, in Lisbon. During her two prisons, in 1965 and 1968, she was subjected to sleep torture, she was beaten, forbidden to go to the toilet, subjected to solitary confinement and humiliated to the extreme. The second time, in 1968, during interrogations, she said straight away: “Last time you destroyed my health, but I tell you again: you can kill me or tear me into pieces, but I won’t tell you anything“. Inspector Tinoco, one of the PIDE torturers, replied: “I am extremely flattered and proud to have ruined your health, but I regret not being done with your life.»

Also listenPortugal between past greatness and duty to remember

The book that had “a bombshell effect” on the dictatorship

Resistance was also taking place in editorial offices and in the world of publishing. One of the books considered by the regime to be subversive, “incredibly pornographic and offensive to public morals” has beenThe New Portuguese Letters, published in 1972 and immediately banned. Maria Isabel Barreno, Maria Teresa Horta and Maria Velho da Costa, the “three Marias”, denounce, among other things, the colonial war, mass emigration, violence, poverty, domestic, social and political oppression on the women. The authors had a trial following this book and were threatened with a sentence ranging from six months to two years in prison, sparking international solidarity joined by Delphine Seyrig, Marguerite Duras and Simone de Beauvoir.

At 86 years old, Maria Teresa Horta, welcomes us to her home in Lisbon, in a living room full of books and admits to us that her book had “a bomb effect» on the dictatorship.

“It is a political book, essentially political, written in a fascist country by three women. I think that at that time, in Portugal, it was not at all strange that this book had such a bomb effect. The book was a scandal. We only understood that this book could be dangerous for us when it was banned…»

The poet recalls that “women were seen as dangerous“if they did not follow the submissive role assigned to them and, therefore, it was “essentially a political book written in a fascist country“. She says that the book was born after an episode of violent attack that she suffered in the middle of the street, “beaten up by fascists» who were angry with him for having published another book,Minha Senhora de Mim, in 1971, which was also banned by the censors and was openly about female desire. “The more I’m banned, the more I do».A few days after the Carnation Revolution, “the three Marias” were acquitted and the judge considered theNew Portuguese Lettersas “a masterpiece”.

► You can listen to these testimonies and many others, in full and in Portuguese, on the RFI Portuguese web page and on podcast listening platforms under the title “Revolução dos Cravos – RFI Portuguese”.