Autobiography

Nathalie Sarraute

“Before the image fades”

Over. CG Bjurström

Lind & Co, 253 pages

Show more

Biography

Ann Jefferson

Nathalie Sarraute. A Life Between ”

Princeton University Press, 425 pages

Show more

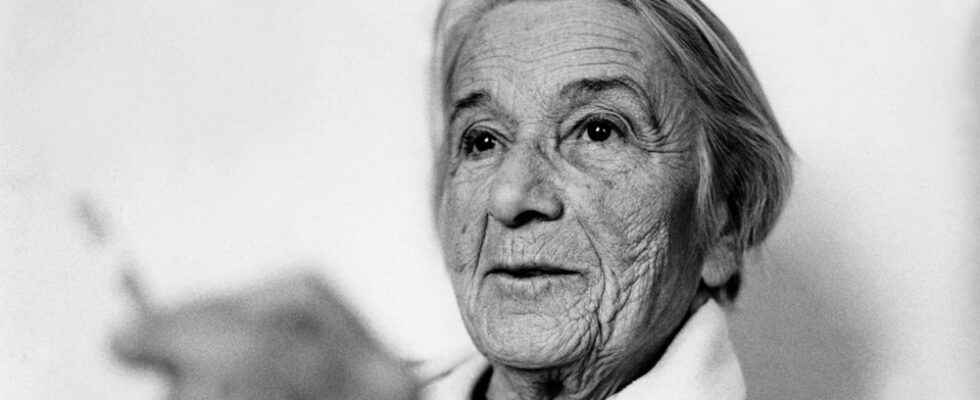

The year is 1958. Outside the premises of the publishing house Éditions de Minuit in Paris, there are representatives of the literary direction that has just been lumped together under the name “the new novel”. Seven authors and their publishers. Of the seven, only one is a woman, Nathalie Sarraute. In the photograph, she stands out clearly with her hands in her coat pockets and her legs crossed. She was older than the others in the picture and had already made her debut two decades earlier. Did she ever belong to the group whose predecessor and role model she was appointed to? The more of her more than a dozen books I read about, the more hesitant I become. Her childhood portrayal from 1983, “Enfance”, which has just been published in a Swedish new edition under its old title “Before the picture faded”, defends its position as one of the last century’s great autobiographies.

Nathalie Sarraute was born Natalia Iljinichna Cherniak in Ivanovo, Russia on July 18, 1900. Her father, Ilija Cherniak, was a chemist and ran a fabric dyeing factory. However, the marriage with mother Polina was not happy and the parents divorced early. A few years after the divorce, the mother does something currently so unusual as to hand over custody to the father, who has meanwhile moved to Paris and remarried. In “Before the Picture Faded”, Sarraute describes the trauma of divorce from her mother. On the train, Polina only follows her to Berlin. From there, the eight-year-old Natasha is accompanied by a “friend” of the family whom she is asked to call uncle. The father’s new wife, Vera, is pregnant at the time and considers the stranger girl to be an intruder. When Natasha during a joint walk asks Vera when they are going home, she answers with unimaginable cruelty: “This is not your home!”

Growing up she is plagued by anxiety attacks and obsessions. She has her “ideas”, as she euphemistically puts it. Already in the opening scene, she is alone in a boarding house with a German nanny. The nanny asks her to hand over a pair of scissors, Natasha does, but with her legs outstretched, and when the nanny points out the mistake, Natasha says that she should tear the upholstery with the scissors. “No, you are not silent” – you do not, says the nanny. “Yet. I will do it “, Natascha answers. And do it.

Already at a very young age, Sarraute develops an almost eerie susceptibility to shifts in other people’s emotional reactions. It is the unspoken in and between people that fascinates her: feelings of disgust, mistrust or envy that flicker past so quickly that it barely attaches to the consciousness. She calls these emotions movements tropicalisms, and it is also the title of the collection of fourteen short prose texts that she debuted with in 1939.

The book did not attract much attention when it came out, it was only printed in an edition of 650 copies, of which Sarraute some time later was offered to buy back just over a third. It was only long after the war when the publisher Éditions de Minuit republished it, with a preface by Jean-Paul Sartre, that Sarraute’s name began to resonate. A younger generation of writers saw in her prose an attempt to reach beyond the character templates of the realistic novel. But it is only when “Tropisms” is reviewed in a daily newspaper together with Alain Robbe-Grillet’s then new novel “Jealousy” that the expression “the new novel” becomes a concept. A year later, the famous group photo is taken, and Sarraute and her more than twenty years younger colleague Robbe-Grillet (far left in the photo) are suddenly guiding stars in a new literary movement.

The British literary scholar Ann Jefferson has in her biography, “Nathalie Sarraute. A Life Between ”(2020) has closely followed Sarraute’s literary career during these years and one can rightly ask from her how“ new ”Sarraute’s new novel really is. According to the manifesto published by Robbe-Grillet a couple of years later (“Pour un noveau roman”, 1963), the new novel is characterized by objectivity and objectivity. Objects, reads a quote from Roland Barthes from this time, are basically just “an optical resistor”. Therefore, they can also not be attributed properties or symbol values.

Nathalie Sarraute meets few of these criteria. In her collection of essays “L’ère du soupçon” (Epistle of Mistron, 1956), she instead highlights Dostoevsky as an exemplary example because he never, unlike Balzac and several other 19th century realists, reduces the individual to a few distinctive characteristics. In Dostoevsky’s, man is instead drawn as a fluid of varying emotional outbursts: stolen invitations, pretenses, condemnations, often contradictory: hatred mixed with tenderness, obedience with contempt. In addition, most of these exchanges take place unknowingly. As one of the first, Dostoevsky realizes, Sarraute writes, that “consciousness is an activity, not a static entity.” It is this activity that should make us read attentively, not silly intrigues, grossly drawn characters or stylish lines.

Much more than that is not “new” in Sarraute’s novel art. An experienced reader recognizes similar literary strategies in Marcel Proust or Virginia Woolf, though not as pointed. It is also not true that Sarraute’s novels lack action. In the breakthrough novel “The Planetarium” (1959), the rudiment to an almost classic plot is found when it follows the couple Alain and Gisèle’s attempt to take over the beautiful five-room apartment that Alain’s aunt lives in and (it is claimed) “does not need”. But the important thing does not occur in or during the conversations that the family members have in different rooms and salons, but at a level below, in the form of what Sartre in the preface to the new edition of “Tropismer” called a “sous-conversation”. Literally in silence, at this level an orgy of hatred and lust, self-flattery and envy is revealed. In particular, the portrait of Alain is skilfully drawn. On the surface, he is portrayed as a sympathetic, listening and compassionate son and real husband, but underneath it hides a striving who, with falsehood and deceit, is prepared to go over corpses in order to cure his feelings of inferiority. Alain is one of many figures in Sarraute’s writing who illustrate what Katherine Mansfield called “this terrible desire to establish contact”, a drive stronger than the sexual drive and which Sarraute believed was behind even the most innocent human acts.

Sarraute was secretive about his private life. Jefferson has only managed to trace a very few passages in her novels or plays that can be traced back to her own experiences or memories. It therefore came as a surprise when, at the age of 83, she published her childhood memories, also in a form that, unlike her previous books, was more immediately available. But Sarraute would not be Sarraute if she did not also introduce to the narrative self a counter-voice, an alternative self, which already on the first page of the book questions not only her motives but also the “authenticity” of the experiences that are reproduced. From this interplay of voices emerges the image of a young, strong-willed woman who is forced to harden herself on the verge of self-violence. For the young Nathalie, school becomes a refuge from the chaos of home. “I loved what was established, boundable, unshakable,” she writes. She also turned out to be a very talented student, which does not stop the stepmother from trying to humiliate her. She hires two British nannies to teach Nathalie’s half-sister English, but forbids the older sister to spend time with them “because she’s already got everything”. Nathalie instead sneaks in to the nannies after the family goes to bed and keeps them awake all night with their talk. She will soon excel in English as well.

In his review of the original edition of “Enfance” (SvD 15/8 1983) Gunnel Vallquist wrote that it must have required great courage on the part of Sarraute to, after a upbringing during which every trust was broken and every act of trust was met with betrayal, re-enter these states where “Everything flows, transforms and escapes”. But Sarraute’s aesthetics were at the same time characterized by an incredible austerity. She protected simple psychological explanatory models. In a time marked by political awakening, she was, she admitted, ideologically blind. She believed that the consciousness movements she listened to were not tied to social status, age or even gender, but impersonal. Or as she writes: “Inside us there is neither an ‘I’ nor a ‘you’, just a ‘here’, where everything happens.” These are the words that also sum up many of the episodes in “Before the picture faded”. Less of a story about an ego in the making, these memoirs are the description of a place and a series of moments, of the “here” where Sarraute’s advanced, sublime novel art would later take place.

Read more texts by Steve Sem-Sandberg and more reviews of current books.