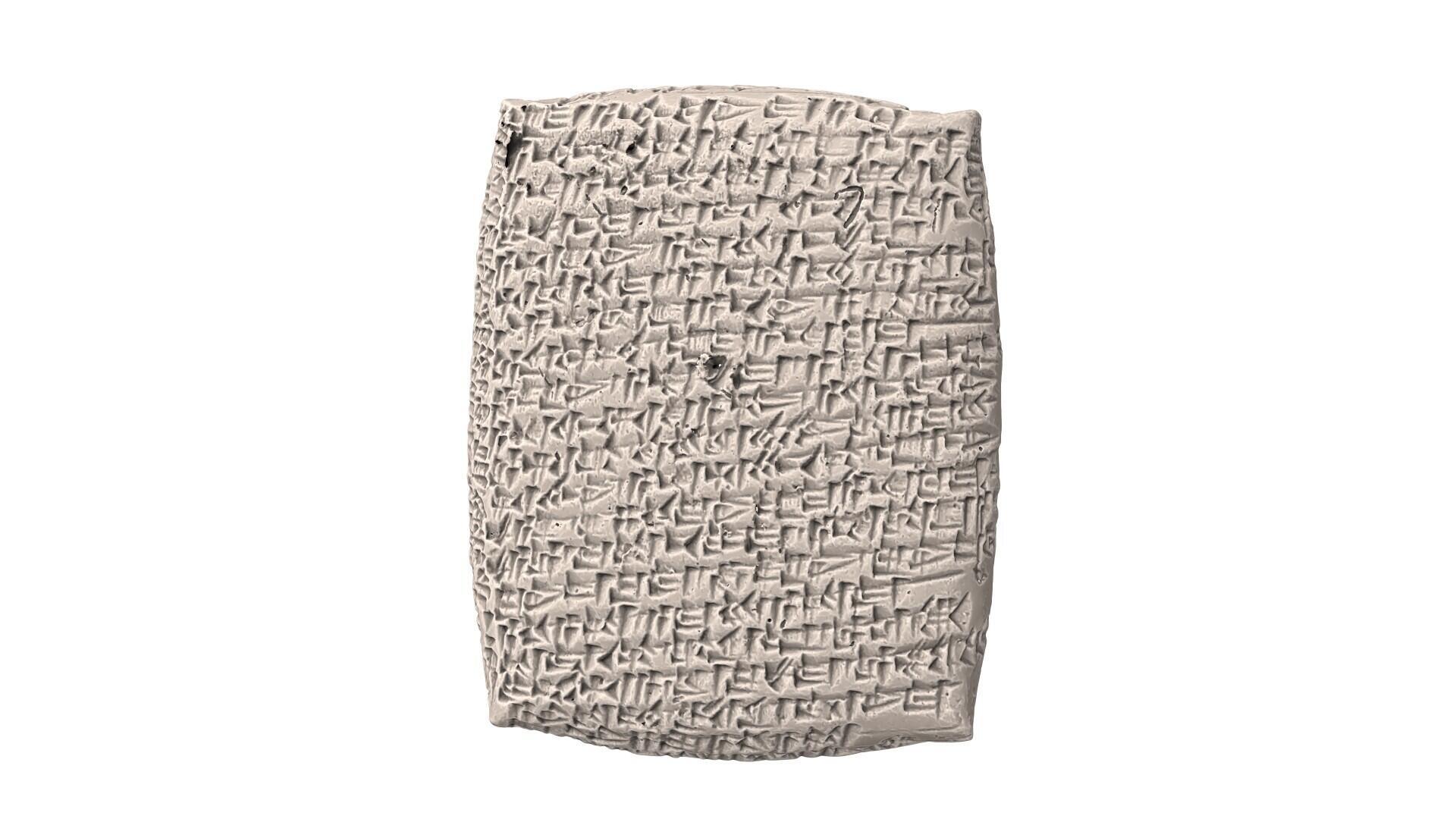

To study the history of the civilizations of Mesopotamia, Assyriologists have a particularly well-preserved first-hand source: hundreds of thousands of clay tablets, found by archaeologists on sites ranging from Anatolia to Near and Middle East. Written in cuneiform writing and in different languages (Assyrian, Babylonian, Sumerian, etc.), they cover three and a half millennia of human history, and provide precious details on the life of the people of Mesopotamia. However, part of the exhumed tablets remained inaccessible to researchers, enclosed in a clay envelope. But a new machine allows them to unravel their mysteries. Meeting with Cécile Michel, Assyriologist and research director at the CNRS, during a stay at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, Turkey.

6 mins

From our correspondent in Istanbul,

RFI: Why were certain cuneiform tablets put in envelopes?

Cécile Michel: In fact, in ancient times, many of these texts were enveloped in clay. This mainly concerns two types of documents. On the one hand, documents with legal value, where one could write on the envelope a summary of the contract or the current affair, as well as seals – that is to say the signatures of the parties and witnesses. On the other hand, letters like the ones we are writing today, put in an envelope to keep the text of the letter confidential and to protect the tablet that was sent. In this case, on the envelope there was only the name of the sender, the name of the recipient or recipients, and the seal of the sender. The seals are representations of small, magnificent miniature scenes, which should not be destroyed. So in museums, we don’t open envelopes.

Why are some tablets still in their envelopes?

We assume that this is either because they arrived too late – the recipients had left, or they were dead – or because there were copies. Contracts had legal value as long as they were in their envelopes, with the signatures of witnesses and parties on them. When the contract was finished, we broke the envelope. Most of the tablets are no longer in the envelope, but there are still many that remain in the envelope. So I had some frustration as an Assyriologist at not having access to the hidden texts. I expressed my frustration to my colleague Christian Schroer [professeur de nanosciences et d’optique des rayons X à l’Université de Hambourg, ndlr]who replied: “ We must be able to do something! »

Christian Schroer designed a scanner, ENCI, which now allows you to read hidden texts. What new does it bring?

Christian and his team have designed a very high definition tomographic scanner which has the particularity of being transportable. As the tablets, which are too fragile, cannot leave the museums where they are kept, the device must go to the museum, which was not possible until now because the scanners usually weigh several tons. [contre seulement 400 kg pour ENCI, ndlr]. We carried out a mission to the Louvre Museum in February. This was our first travel experience with ENCI. We worked in the reserves, in the second basement, and the day the machine arrived – proof that the problem of transport and weight is important – the elevator broke down! So we had to go down everything on foot. This demonstrated the fact that we indeed had a transportable machine. ENCI is held in eight boxes, the heaviest weighing 100 kilos.

After the Louvre, you complete a three-week mission at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara. Why this museum?

There is a site in Anatolia called Kültepe by its modern name, Kanesh by its ancient name, where Assyrians coming from Northern Iraq came to settle in the 19th century BC to organize commercial exchanges in long distance. They imported tin and fabrics into Anatolia, and in exchange brought gold and silver to northern Iraq. And on this site, for more than a century, they left records written in Old Assyrian – a dialect of Akkadian – and written on clay in cuneiform. It is the first trace of writing in Anatolia. This site, which has been excavated continuously since 1948, has produced to date some 23,000 tablets, of which approximately 10% are still in envelopes. Around 17,000 are kept in this museum.

During your stay, thanks to the machine, you were able to decipher texts that no one had read for around four millennia…

It’s quite extraordinary! For example, I was finally able to read a very long tablet, 60 lines long, which was enclosed in its envelope and whose envelope I had published in 1997. It is a fascinating text: a letter which traces the fact that There has been a trial between several people and they are trying to untangle the matter to see if we can find a solution. In 1997, when I published the envelope, I only had the three lines of the letter’s correspondents! At the moment I am working on an archive that was exhumed in 1993 and which belongs to two and a half generations of Assyrian merchants based in a house in Kültepe. The idea is to reconstruct the history of their lives, their business practices, the relationships with their wives, their wives, their sisters, who remained in Northern Iraq… There is an extraordinary mine here on the condition of women. It is very rare to have so much data on women at this early time. With a colleague from the CNRS, we also made a documentary film (“Thus speaks Tarām-Kūbi, Assyrian correspondences”), in which we gave voice to one of these women, who wrote from northern Iraq to her brother and her husband who had gone to Kültepe.