“We are at war”. On March 16, 2020, Emmanuel Macron announced the first confinement. Faced with Covid-19, France is barricading itself. The streets empty. Nature even takes back its rights, here and there. Two months pass before the French taste their freedoms again. They will be forced to lock themselves in their homes twice more. A torment.

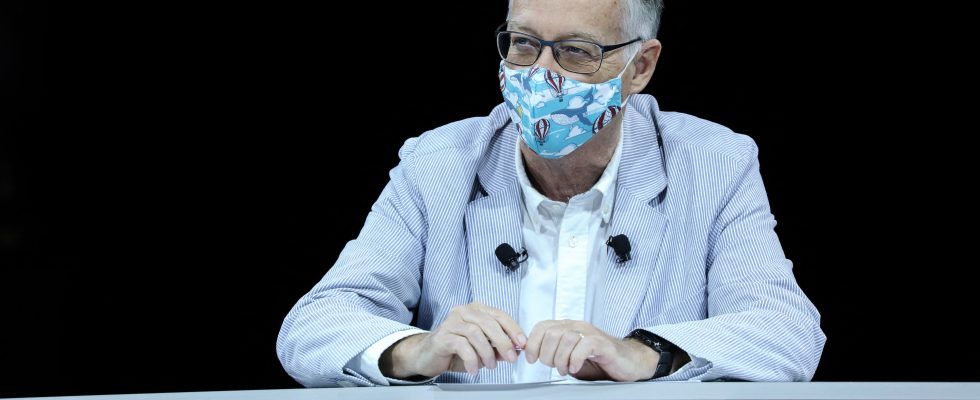

Three years later, what remains of the health crisis? Despite a difficult winter, confining seems surreal again. “We have left the emergency, believes Antoine Flahault, but significant challenges remain”. Seasonal epidemic, long Covid, mutations, disease X… The epidemiologist at the Geneva Institute of Global Health delivers his vision of the post-coronavirus period.

You, and your institution, have been one of the main players in the world of monitoring the Covid-19 epidemic. In France, three years ago, we confined. From now on, we say that the Covid is over, that we have to move on. Have you moved on?

We’re all moving on! The institutions, the governments, the peoples are no longer in this permanent state of alert, where the information was always more worrying, where we had the feeling that the situation was not under control, where we had not enough vaccines or vaccinated people.

The virus could come back in force, it is possible, nothing is to be excluded, but the paradigm has changed. We left the ER. Public health officials are therefore less solicited. I can finally devote myself to other subjects, even if the Covid and the post-Covid still take up a lot of my time. Significant challenges remain.

Can we say that the epidemic is over?

Not officially, anyway. The WHO has still not spoken. How and when will she do it? To understand how the end of a pandemic is decreed, let’s go back. It is August 10, 2010. Margaret Chan, then Director General of the WHO in Geneva, declares the end of the H1N1 flu epidemic.

On what basis? The WHO health emergency committee had, a few hours earlier, reduced the alert level for this disease. We must therefore wait for this to be done in the same way for the Covid-19. The health emergency committee led by a Frenchman, Didier Houssin, met in January 2023. This could have been the announcement of the end. But at the time, the epidemic was blazing in China. In order not to have to back down, the WHO preferred to wait. The committee is due to meet again in April… Make an appointment.

We can expect that, as in 2010, the WHO recalls that the virus has not been eliminated, that there are still ongoing epidemics of Covid-19 in the world, serious forms, death. That we are not immune to a new mutation, of course. But that, despite everything, health systems have entered a post-epidemic phase.

After that ? Caregivers throw off their coats and epidemiologists drop the numbers?

Not really, no. In France, in 2022, there were still 40,000 deaths from Covid-19, and several million French people are suffering from a long Covid, for which there is no cure. We must therefore continue to vaccinate people at risk, ensure that we are in a position to properly take care of the patients who continue to arrive, and not cut funding for research and health monitoring – which , by the way, was disastrous in France. The French way of quantifying the circulation of the disease is light years away from what the United Kingdom has done, for example, with tests carried out on volunteers, in representative samples. A form of survey, in short, much more precise.

We are entering into a long management of the Covid-19. It’s good news ?

Not really, no. Politicians have shown great ingenuity during the acute phase of Covid-19. Realize that in Switzerland, where I work, the leaders have transformed the country into a centralized nation, by temporarily conferring on Bern the central political powers. They have francized their way of governing. Isn’t that remarkable? [Rires] Urgency is a formidable political lever.

The long time, much less. The French president is not at war against tobacco, obesity, alcoholism, air pollution… I am not very optimistic about the post-pandemic phase that is coming. Because it would be necessary to introduce preventive measures which have never been appetizing for politicians and citizens.

In other words, we are much better able to treat ourselves once bedridden than to avoid getting sick. Thinking about the end and after Covid-19 in terms of public health will therefore be a challenge at least as important as it has been for the past three years. If the Covid-19 kills at the current rate, we will reach a balance sheet similar to the acute phase of the pandemic in about five years. And to manage this balance sheet, there will be no Defense Council.

Is long-term management the most difficult thing in a pandemic?

Take the example of Cholera. In 1854, John Snow, a British doctor demonstrated the role of drinking water in the transmission of the disease, which is terribly rampant in Paris, Berlin, and London. This doctor, one of the first “epidemiologists” in the world, goes door to door and identifies that all the cases are connected to a pump, itself fed with water from the Thames. He has the crank removed. The epidemic stops. A flamboyant demonstration, isn’t it? Well, it will take more than 50 years for cities to rethink their water management. The time that we understand that the development effort was going to be profitable in the very long term.

In the 20th century, cholera taught us to evacuate waste water. What is the lesson to be learned this time around?

The Covid-19 teaches us the importance of air purification, ventilation of our places of life and work, of our transport. For me, it’s a bit like the sewage of the 21st century. Influenza, Covid, measles, chickenpox, whooping cough, tuberculosis share this mode of transmission by aerosols. All these diseases could benefit from the same measures, and many people could be saved. But few governments have tackled it. It is one of my hobbyhorses, in the WHO expert group that I chair for the Europe region, and within the collective that I founded to inform science about this new public health issue.

Let’s look longer term, again. Where could the next pandemic come from?

The WHO has made a list of about ten infectious agents that could generate a pandemic. They include: Ebola, the coronavirus, the flu and at the end, disease X, the one that no one foresees, but which could occur. What could it be? Mystery. Global changes, climate change, deforestation, increased mobility and population favor epidemics. Unfortunately, we should have new alerts. We must not let our guard down. What to avoid are the Maginot lines. Telling ourselves that we are going to prevent all diseases, by modeling on what we have learned from the Covid. If ever the next pandemic is a disease that is transmitted by a mosquito, or by water, it will not have much effect.