On October 9, 2014, learning that the Nobel Prize for Literature had gone to Patrick Modiano, we went with François-Henri Désérable to experience the event live, at Gallimard. In the street, it was the hustle and bustle of a big day: lots of journalists were crowding around, waiting for the arrival of the lucky winner. At one point, a black car with tinted windows appeared at the end of the street. She had driven very slowly, before parking right in front of Gallimard. Finally Modiano arrived! Except that it wasn’t him who got out of the taxi, it was Philippe Sollers. Disappointed, the journalists turned their backs as if it were just an ordinary person.

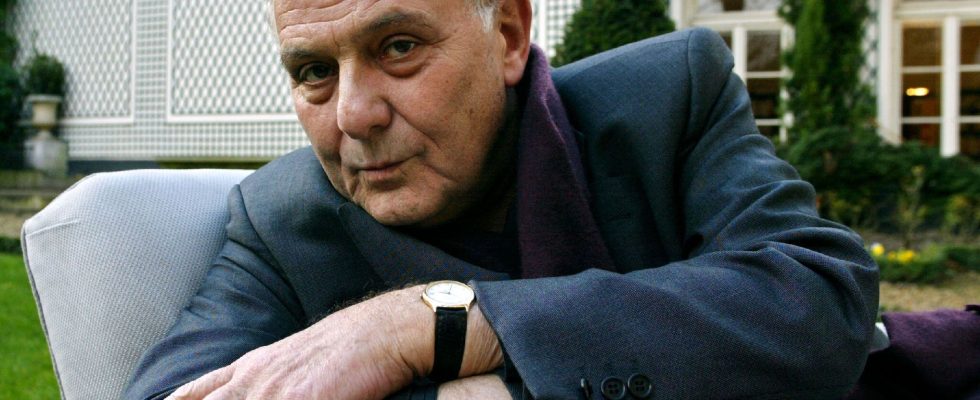

The scene had something twilight about it. Sollers will have seen Jean d’Ormesson enter the Pléiade; and Le Clézio, Modiano and Annie Ernaux receive the Nobel. After having reigned for a long time over the republic of letters (columnist at World and to The Obs, influential editor at Gallimard), he ended up being gradually obscured. In recent years, no one read his new works anymore, with the possible exception ofSecret agent (2021), for which he enjoyed renewed interest in the micro-community of writers. His death on May 5 provoked relatively few reactions. Gallimard is today devoting a tribute book to him where we find all his faithful allies and heirs (Bernard-Henri Lévy, Josyane Savigneau, Yannick Haenel). If he gives Sollers the image of a free, amusing and warm man, he reinforces us in this idea: did he not put his talent into his life more than into his work?

Let us recall in a few words what the golden legend of Sollers was. Born in 1936, he made his breakthrough in 1958 with A curious solitude, a first novel praised by both Mauriac and Aragon. Medici Prize at 25 years old for The park, he then lost himself intellectually in Maoism and literaryly in a vague experiment – which did not prevent Roland Barthes from celebrating him in 1979 via his essay Sollers writer. The enfant terrible of letters became institutionalized in 1983: he joined Gallimard (which he nicknamed the “central bank”), both as collection director (L’Infini) and as an author (Women).

An elusive man, both provocative and cautious, refined and Florentine, he published numerous dandies (Bernard Lamarche-Vadel, Frédéric Berthet, Jean-Jacques Schuhl) and two now cursed writers (Gabriel Matzneff, Marc-Edouard Nabe). His career as a publisher was not without quarrels, the most shattering being his breakup with Philippe Muray. As a writer, if his Nietzschean esthete novels are repetitive, complacent and hollow, he shines through the accuracy of his admirations and his erudition, as his collections of articles prove. The War of Taste, In Praise of the Infinite And Perfect speech (less Runaways…). Let us add that this media animal burst onto the screen, which undoubtedly did as much harm as it helped him – Sollers may have adored Guy Debord, but the guru of situationism considered him in return as an “arriviste”, a “peacock” and even a “shit” (words used in a letter to François Bott dated February 4, 1991)…

“To live hidden, let’s live happily”

In Tribute to Philippe Sollers, several of his relatives, including Jean-Paul Enthoven, quote his motto (forged by a slight diversion as he appreciated them): “To live hidden, let’s live happily.” The young Sollers met Dominique Rolin in 1958, before marrying Julia Kristeva in 1967. A clandestine love, an official marriage: for decades, this man of fixed passions led a double life, going to the island every year de Ré with Kristeva and in Venice with Rolin. This gave him a serious point in common with François Mitterrand, his double in politics.

Another similarity between these two strategists is that it was not known whether Sollers was right or left. False socialite, true solitary, this great dissembler moved forward masked, illuminating his writings with his cheerful knowledge and his daily life with his joy, remaining silent about the rest, and in particular about his moments of melancholy. We find in Tribute to Philippe Sollers a text by Frédéric Beigbeder which ends with these words: “Philippe Sollers tells the story of a man who takes his apocalypse for a generality; and the worst is that he is perhaps not wrong: the death of Sollers may coincide with the end of the world.” A bit excessive, certainly; let us rather say that with his disappearance a certain idea of literary life is erased.

Tribute to Philippe Sollers, collective work. Gallimard, 144 p., €12.

.