In an address to rectors delivered on August 25, 2022, President Emmanuel Macron announced the creation of an educational innovation fund. Endowed with 500 million euros, its aim is to finance innovations at the initiative of establishments. In the general context of a centralized and top-down educational policy, with very limited autonomy and means for schools, this fund could be an exceptional opportunity to advance the entire educational community, by trusting teachers, by giving them the power to act and the means to do so, all for the benefit of the students.

However, members of the scientific council for national education (CSEN), while excited about the prospect, also voiced some concerns. And all the more so since the instructions given to the rectors mentioned the need to disburse this fund as quickly as possible, without selection criteria, without the imperative of evaluating the results, all while invoking “the right to make mistakes”. A strategy based on a first experiment launched in 2021 in Marseille schools, which no one knows if it produces the expected effects. And for good reason, no evaluation process has been undertaken.

The risk of projects without any benefit for the students

The problem of having no selection criteria is that we know in advance that some schools will engage in good faith in projects without any benefit for students or teachers. In fact, with or without the fund, some teachers and establishments are already enthusiastic about Brain Gym – physical activities supposed to facilitate communication between the hemispheres of the brain -, learning styles, multiple intelligences, cardiac coherence, reiki – a Japanese pseudo-medicine -, and many other concepts and practices without scientific validity and without any established effectiveness. How many such projects will the fund finance?

Of course, the right to make mistakes is a good principle. Researchers know better than anyone that not all experiments can produce the expected results, and that is part of the job. But that’s why when they consider a new experience, they start by relying on the results of past experiences, and more generally on all the knowledge accumulated up to that point. The right to make mistakes is not the right to repeat past mistakes. But in education, in pedagogy, we are not starting from scratch. There is much more knowledge in this area than most people realize.

The effectiveness of countless teaching practices already evaluated by science

In 2008, the New Zealand researcher John Hattie published the book Visible learning. Its ambition was to synthesize all the most solid research in the field of education. For this, it has identified more than 800 meta-analyses, that is to say studies that statistically compile the results of other studies on the same subject. These 800 meta-analyses brought together the results of more than 50,000 studies, covering more than 100 million students in several dozen countries. Since 2008, the volume of international research published in the field of education has doubled again. One can consult summaries extremely well done on the site of Education Endowment Foundation (in English).

In short, we already know a lot about education. Countless teaching practices have been tested, modified and retested by numerous research teams in various countries. Before getting excited about a new idea, it might be wise to check whether it has already been tested and whether it has not already been put away for a long time as false good ideas. And for institutions wondering, among the countless possibilities available to them, which projects would be likely to meet their needs with a good chance of success, it would be very useful to be able to consult a list of ideas. which research shows have worked well for other institutions before them.

13 good ideas validated by science

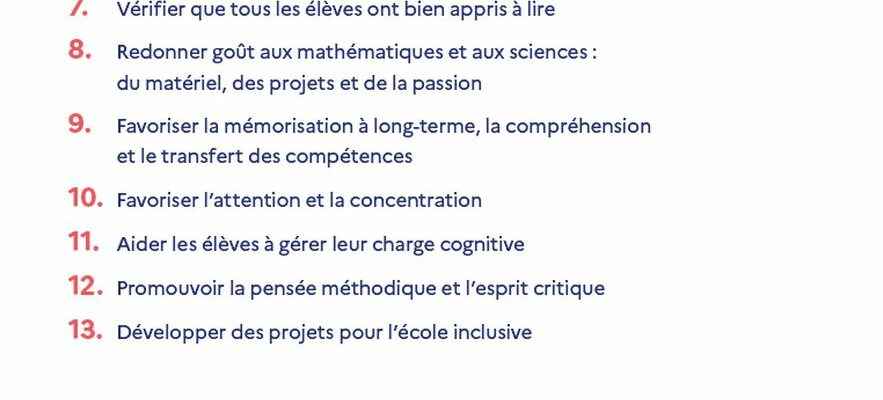

This is why the CSEN published, on Tuesday 13 December, a document entitled “Some good ideas for educational innovation”, which is based on international scientific research in education to extract 13 suggestions, pedagogical approaches or practices which have already largely proven their effectiveness in many countries, and which are just waiting to be adopted massively by French establishments. While preserving the freedom of establishments to take initiatives and engage in the projects they choose, the CSEN therefore pleads for this freedom to be informed and guided, to avoid that all the space of possibilities is (still ) explored as if it were a vast terra incognita.

The 13 good ideas of the CSEN.

© / CSEN

Beyond this a priori guidance, it would also be desirable to promote a rigorous evaluation of the results given by the various projects. Not all will work, it is inevitable and it is not necessarily serious. The main thing is to be able to learn from your failures. It is still necessary to be able to determine which project is a success and which project is a failure. It’s not as simple as it seems. We cannot just rely on the satisfaction of the various stakeholders, which may be completely out of step with the pupils’ academic results, or with other objective indicators relevant to the project.

A necessary evaluation method

It is therefore necessary to adopt an experimental methodology, comparing different projects aiming for the same goal but using different means, on common indicators chosen at the start. For example, establishments having projects financed by the pedagogical innovation fund aimed at improving the school climate could be supported in determining together the relevant indicators, adopted by all and measured at the beginning and at the end of the project. In this way, we would give ourselves the means to determine which projects will have worked better than others.

The right to make mistakes is a laudable step, but with it comes the imperative to learn from mistakes, which in turn requires a method to reliably distinguish between successes and failures. Without such an evaluation process, France runs the risk of spending 500 million euros without being able to learn anything from it, and of proving in the end incapable of saying which projects will have worked and would be likely to serve as inspiration for future investments.

Franck Ramus is a research director (CNRS), he works at the Laboratory of Cognitive Sciences and Psycholinguistics (ENS), and is also a member of the Scientific Council of National Education.