We know that the balance of the intestinal microbiota is a key element for the good health of the organism. On the other hand, the links between genetics and the composition of the microbiota are in the process of being understood.

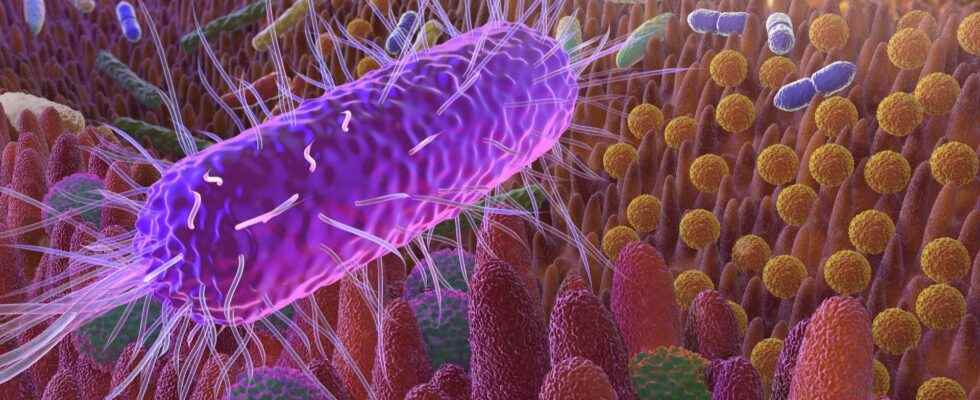

Our digestive tract inhabits billions of microorganisms : bacteria, virusesand mushrooms. These line the walls of the intestines, particularly those of the large intestine (colon). This is called the gut microbiota or intestinal flora. These micro-organisms live in symbiosis with our body, which is their host. An imbalance of the microbiota can trigger many pathologiesincluding autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

Our microbiota is gradually formed from birth until adulthood depending on diet, level of hygiene, medication received, environment but also depending on the genetics of the individual. It is the link between human genetics and intestinal microbiota that a team wanted to explore further. Their work was published on March 9, 2022 in the journal Scientific Reports from the Nature group.

Analyze multiple mutations at the same time

When a disease is the consequence of a single genetic mutation, it is relatively easy to identify it. If it is the substitution of a single nucleotideit is called a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP Where Single Nucleotide Polymorphism, in English). Most of the existing studies on the relationship between human genetics and microbiota composition have looked at the influence of a single SNP at a time. The authors of this study wanted to identify the role of several SNPs at the same time thanks to a particular statistical process: extended canonical correlation analysis. It is a multidimensional descriptive statistical method. Thus, the links between SNP and occurrence of certain diseases (diabetes type 2, neurological disorders, cancer) were tested in 250 individuals, 35 pairs of monozygotic twins (n=70) and 90 pairs of twins dizygotic (n=180).

New associations between genetics and microbiota

Thanks to this new method of analysis, the authors were able to demonstrate that certain functions, such as antibiotic resistance, were directly related to the patient’s genetics. Known associations between genetics and microbiota composition could be confirmed and new correlations could be identified. The authors acknowledge that their cohort is small in size and lacks diversity (only UK participants). They would like to continue their work with a greater number of subjects, from various geographical and cultural areas. Similarly, everyone in the cohort was in good health. It would be interesting to carry out the same work in people with diseases. There is no doubt that a better understanding of the microbiota will allow better management of diseases caused by its imbalance.

Interested in what you just read?