Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan’s film, has the merit of showing that, contrary to a widely held belief, Albert Einstein had no part in the design of the atomic bomb: he was unaware of the Manhattan Project! But then, why does the image of the father of relativity remain so strongly “entangled” with the specter of the atomic bomb? For two somewhat misleading reasons. The first is the famous letter of August 2, 1939, signed by Einstein and addressed to President Roosevelt. It was actually a question of warning him of the possibility that the Nazis were making an atomic bomb, and not of asking him to start building one (which the Americans did not decide until October 1941). The second reason is the systematic amalgam between atomic bomb and E = mc2. This confusion began a year after the first test of such a bomb, on July 16, 1945 in New Mexico. To commemorate him, the magazine Time dated July 1, 1946 featured a striking depiction of Einstein on the cover, baptized for the occasion cosmoclast, i.e. “the destroyer of order”. It shows the benevolent face of the scientist, mane in battle, marked features, the gaze carrying into the distance. In the background, a column of flames and smoke rises towards a cloud in the shape of a cobra’s head. Written on the cloud, the equation E = mc2 symbolizes the Faustian pact that the most theoretical physics would have concluded with the most concrete evil.

Yet, E = mc2 has neither more nor less connection with the atomic bomb than with the cracking of a match or the fall of a pencil. It is indeed a universal formula, which applies to all phenomena in which energy is exchanged or transformed, even if no light intervenes in the matter (allow me in passing to insist on this fact: the speed of light intervenes everywhere, including in the processes in which the light itself does not intervene!). Nothing in this formula suggests the process by which the energy contained in a piece of matter could be released, much less the energy contained in an atom…

An absolutely accidental discovery

In reality, the atomic bomb owes almost everything to the discovery absolutely fortuitous, in December 1938, by Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn, of a singular and amazing property of the nucleus of an isotope of uranium, uranium 235: struck by a neutron, this nucleus is capable, like a pear, of split in two releasing a large amount of energy. In the months that followed, other physicists will establish that following such a fission of a uranium 235 nucleus, two or three neutrons are emitted, which can then strike other uranium 235 nuclei. , which in turn fission, each emitting two or three other neutrons which will strike as many uranium 235 nuclei, and so on. There – and only there – it was understood that the fission of a nucleus of uranium surrounded by many other nuclei of the same nature could cause an explosive chain reaction.

On August 6, 1945, when he heard by the radio the dropping of Little Boy on Hiroshima, Einstein could only articulate these words: “Poor me!”. Very touched by the tragedy in Japan, which he had visited in 1922, he seemed to have pressed the button himself. He quickly understood the extent of the disaster: the explosion at six hundred meters altitude, accompanied by a lightning flash, followed by a ball of fire and an overpowering shock wave which made the bodies vibrate until rupture, burning the flesh, instantly killing thousands of people. But, three months later, he wrote: “I do not consider myself the father of the liberation of atomic energy. My role in this matter has been quite indirect. In fact, I had I didn’t think she would be released in my lifetime. It only became possible following the accidental discovery of the chain reaction, and it’s not something I could have foreseen.”

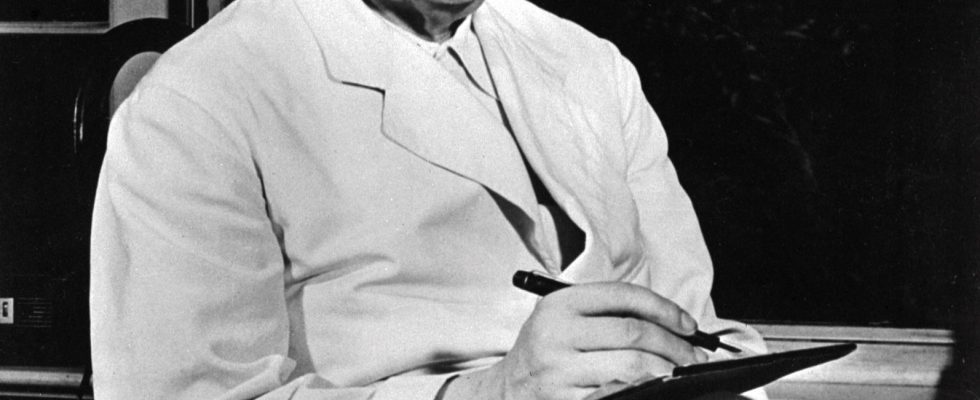

Robert Oppenheimer himself described Albert Einstein as a being of great kindness: “If I had to define in one word his attitude towards human problems, I would choose the Sanskrit word Ahinsawhich means “to do no harm”. Such is therefore the supreme and tragic paradox of the atomic bomb: it was the ultimate but very indirect result of the epistolary act of a gentle man.

* Etienne Klein is a physicist, director of research at the CEA and doctor of philosophy of science.