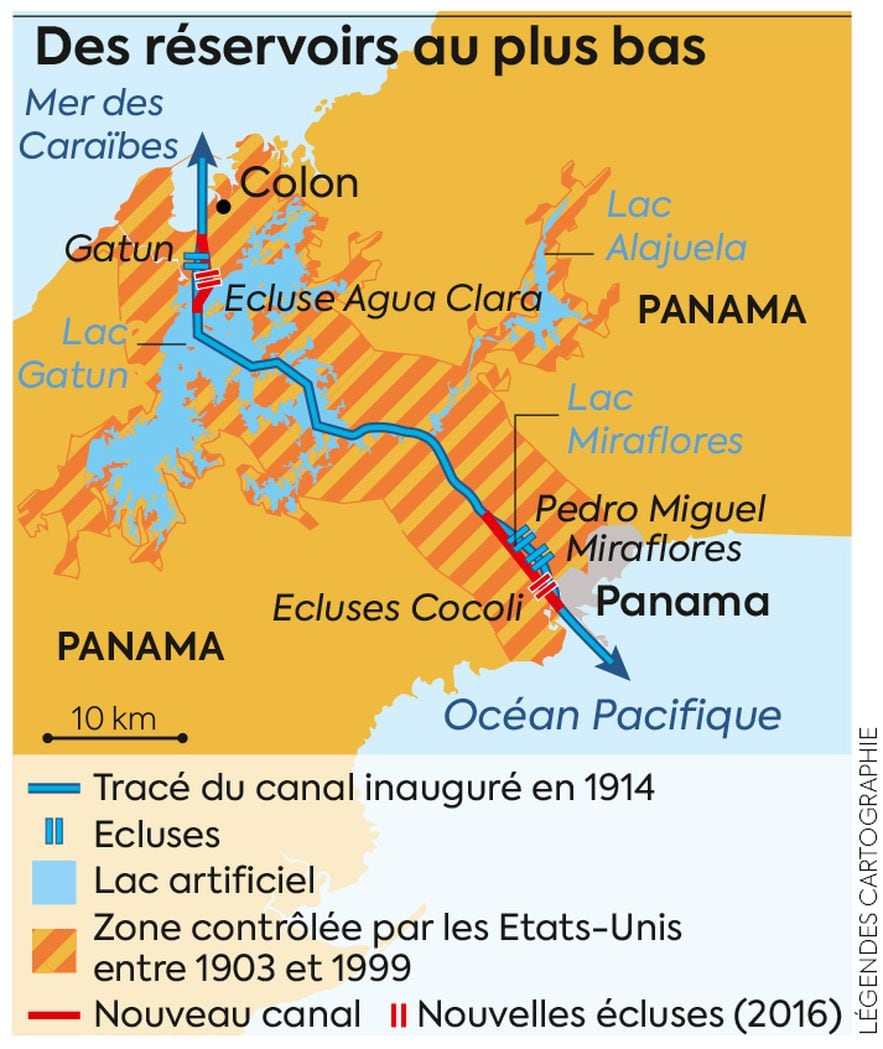

This is a threat that Ferdinand de Lesseps did not foresee. In 1882, the French entrepreneur began work on the Panama Canal, a decade after the inauguration of the Suez Canal. A titanic construction site in the middle of lush Panamanian landscapes damaged by yellow fever. Abandoned by the French who “drowned” in the “Panama scandal”, the work was completed by the Americans and inaugurated in 1914. A century later, the canal faced an unprecedented problem in its long and eventful history: the lack of water.

Panama, one of the five wettest countries on the planet, is facing one of the worst droughts in its history. “2023 will be the driest or second driest since we’ve been collecting data,” says Steve Paton, director of the monitoring program at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, which has a base on Gatun Lake, one of two reservoirs supplying the canal with fresh water.

The interoceanic route records a precipitation deficit of around 30% compared to normal. Each time a ship passes through the structure’s locks, 200 million liters of fresh water go into the ocean. The Panama Canal Authority (ACP) therefore made a historic decision: to reduce the number of transits. From 38 to 32 every day, then to 25 in November and 22 in December. “There is no other solution,” explains Ayax Murillo, head of the ACP meteorology office. “Because the priority is to meet the water needs of the population.”

Aerial view of cargo ships waiting to access the Panama Canal, August 23, 2023 in the Bay of Panama

© / afp.com/Luis ACOSTA

The canal, which connects 180 shipping routes between 1,920 ports in 170 countries, represents 6% of global trade. The impact of the slowdown in activity is not without consequences. Queues at the entrance to the canal are increasing (they exceeded 160 cargo ships last summer) and toll prices are exploding. Depending on the value of their cargoes, commercial ships take alternative routes. “Some container ships go around South America via Cape Horn,” explains consultant Jorge Quijano, former canal administrator. Others, coming from Asia, take the Suez Canal to reach the east coast of the United States. -United.”

© / Legends Cartography

“If we don’t adapt, we will disappear”

But the Suez route, which represents around 12% of world trade, also poses a problem. Blame it on Yemen’s Houthi rebels who attack merchant ships in the Red Sea. Maersk, the Danish freight giant, has suspended its passages through the Suez Canal and its ships are now circumventing the Cape of Good Hope.

Although we should not necessarily expect a sharp increase in the price of products in Europe – the cost of transport remains limited compared to the final price – the impact on supply chains is no less significant. . In December, Ikea warned of risks of delivery delays. Tesla suspended activity at its German production plant for two weeks due to parts shortages.

“Other constraints would have to be added to these complications to have a significant impact on the world economy,” however, believes Panamanian economist Felipe Chapman, who considers the situation still manageable. In Panama, the dry season is just beginning and will last until May, the prospects for an improvement in the situation are low. “Lake Gatun will probably reach a historic low level,” predicts Steve Paton. For his part, Ayax Murillo assures that “the crucial measures taken since July will make it possible to maintain a flow of 20 to 24 boats until the rains return”.

In the meantime, the ACP is concerned about the long-term viability of the canal. “We must find solutions to remain a major trade route. If we do not adapt, we will disappear,” canal administrator Ricaurte Vasquez Morales warned in mid-August. The concern is all the greater as Steve Paton’s hydrographic data, which goes back one hundred and forty-three years, prove that “the three driest years (1997, 2015 and 2023) occurred during the twenty-five last years”. Aware of the danger, the Canal Authority is studying the construction of new water reservoirs on the heights of Panama.

.