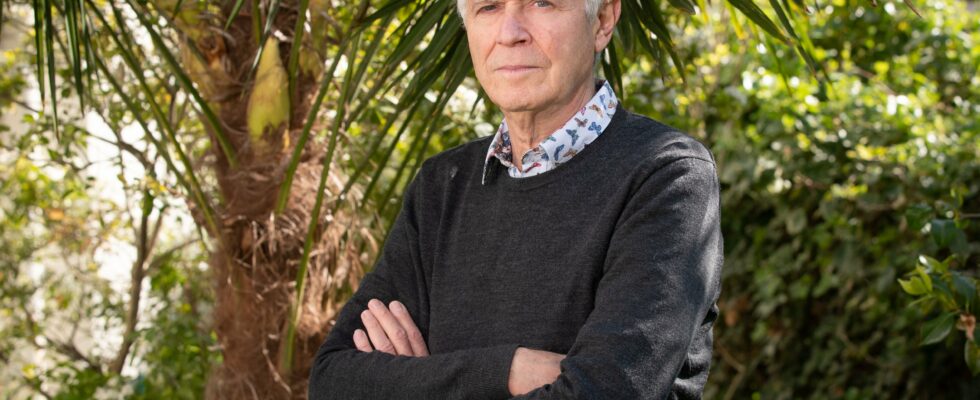

An anonymous Parisian neighborhood. A street of Alcyonian calm. A restaurant like any other, not really plush or fancy either. A back room closed with a thick curtain, far from curious eyes and wandering ears. One table, ten guests. The rebellious “rebels” François Ruffin, Clémentine Autain and Alexis Corbière, the socialists Boris Vallaud and Johanna Rolland, the ecologists Eric Piolle and Cyrielle Chatelain, and the communists Elsa Faucillon and Sébastien Jumel. Between two strokes of the fork, the band understates “the path of the left towards 2027”. Everyone has taken a vow of silence regarding these secret feasts which have been held for a little less than a year. Sitting at the end is the host of these dinners where everyone pays their share of the bill. Olivier Legrain, slender and graying amphitryon, smiling and 71 years old. At this age, we have had “several lives”, says this former industrialist who made his fortune before becoming a psychotherapist late in life and now a millionaire in the service of the left.

His first life was communist. His polytechnic father thought he was a Gaullist, like him, but the revolutionary speeches that resounded in the courtyard of the Buffon high school in the 15th arrondissement of Paris in 1968 captivated him. His second life as a boss occupied three quarters of his existence, first with the chemist Rhône-Poulenc, then Lafarge and its subsidiary Materis, a specialist in construction and painting materials which he removed from the fold of the French cement manufacturer in 2000. “That’s how he became rich,” recalls one of his traveling companions. “Multimillionaire”, he corrects immediately, smiling a little ashamed: “I don’t really like talking about my money” If Olivier Legrain makes his money so well, it’s because he has become a master of LBO (leveraging). buy-out). A financial operation as juicy as it is risky where an investment fund is called upon to buy the company with large amounts of debt. A practice that the left reviles but which has made Legrain famous, who even chairs a pro LBO lobby, Clover.

“He is one of those people who worries about the political future”

Materis initially grew with its 2 billion euros in turnover and its 10,000 employees, before taking the full brunt of the 2007 crisis. Debts spiraled out of control, and the company was sold to the cut eight years later. Legrain was then 62 years old, young enough to begin a third life as a psychologist, and rich enough for a fourth as a patron. He gave life to Riace in 2020, an endowment fund which helps refugees into which he injected 3 million euros in hard cash, to the aid of the anti-liberal and environmentalist left-wing weekly. Politisoffers a few crowns to Regardsanother left-wing newspaper, and is still fighting today for a “house of free media” in Paris and that these newspapers but also Mediapart, Basta, Economic alternatives and the magazine Spirit. In 2022, he signed a check for 400,000 euros for the Popular Primary, this process of left-wing activists supposed to nominate a common candidate during the last presidential election and which turned into a fiasco.

“If you want it to work, avoid calling them primary”

A thousand lives are so many contradictions, except for Olivier Legrain. In the world of employers, as quiet as it is fierce, where we don’t talk about politics, left or right, we describe him as “atypical”, if not sometimes “heterodox”. “Olivier has political and philosophical convictions anchored on the left and which he has never hidden,” sketches his friend of thirty years Jean-Pierre Clamadieu, the chairman of the board of directors of Engie. Another of his friends, a great industrialist, again: “He is one of those people who are worried about the political future. It’s sincere, but he has a lot of illusions.” Legrain looks at politics with as much hope as despair. “He has no political ambition but he is a tireless activist for the union of the left. He tries to get people to talk to each other, and that is already a lot,” defends the former president of the National Council of digital Benoît Thieulin who was part of the adventure Ségolène Royal 2007 and François Hollande 2012.

In the clandestine dinners that he organizes with the “gang of nine”, Olivier Legrain speaks little, listens and questions like a maieutician. François Ruffin and his friend Sébastien Jumel, Boris Vallaud and Johanna Rolland, Éric Piolle and Cyrielle Chatelain, Elsa Faucillon, Clémentine Autain and Alexis Corbière, these deputies or mayors of big cities, elected left-wing personalities, what is so special about them to his eyes ? “Everyone knows that no one can win alone, everyone is driven by this desire for union,” a guest simply admits. The table includes three aspiring candidates – Autain, Ruffin and Vallaud – who would happily participate in a left-wing primary. We are thinking about the conditions for the success of such a process while Jean-Luc Mélenchon and his rebellious France categorically refuse it. The subject was raised one evening with political science professor Rémi Lefebvre, a specialist in primaries. “If you want it to work, you have to start by avoiding calling them primary,” recommended the academic.

A competition, but with what means? How many voters? A few hundred thousand or millions like that of the PS in 2011? François Ruffin and Clémentine Autain have warned that they will not embark on a little dip with only 400,000 registered as during the popular primary in 2022. The method of designation must be a launching pad for whoever emerges victorious. Is this why François Ruffin is hardly enthusiastic about the idea of a council of wise men mentioned by the socialists? The polls, in which he is leading on the left, suit him well. The rebellious rebels doubt. Have they come all this way with Mélenchon and today against him to find themselves behind a socialist?

“I need your money”

The nine talk about the common program of the left. A moment when the discussions rub the most. Legrain dares to interfere a little more with his former boss’ hat. “We need a serious program, which comes to fruition financially,” he repeats, raising communist and rebellious eyebrows. In front of L’Express, the person concerned moderates: “We must imagine a credible project but which must be something more radical than François Hollande’s five-year term.” Mélenchon, at the center of conversations too. No one around the table is fooled by the rebellious leader’s desire to run for a fourth presidential candidacy. Legrain considers that an alternative must be found for him, others say that he must be sidelined, and the city councilor of Grenoble Eric Piolle gets annoyed, demands that we stop saying “that we must do without Mélenchon”. “He’ll be there one way or another.”

“The left must also have powerful people who carry its program”

There is one who was more surprised than the others to find himself at Olivier Legrain’s table. François Ruffin, famous for his harsh criticism of employers, initially hesitated, wondering about the motivations of the multimillionaire. The two men first had to get to know each other, money did the rest. When the rebellious deputy from the Somme launched a call for donations on his YouTube channel in March 2023, proclaiming “I need you, I need your money […] to take a step forward”, Legrain does not hesitate. “I, at one point, helped François Ruffin, Clémentine Autain and Éric Piolle”, he confirms without saying more about the amount of a check which did not exceed 7,500 euros, the ceiling set by law “We are not in the United States… It is not the money that I am going to give that will help the candidates”, puts Crésus into perspective. left Ruffin and Autain would not say so much. They know that at La France insoumise, the safe is well guarded, and that Jean-Luc Mélenchon – this squirrel “who never pays for a coffee”, say his friends. – will not give so easily the 8 million euros of public funding collected annually since the last legislative elections Money does not buy happiness but in politics, it helps to emancipate oneself “François is looking for his war chest. financial freedom so as not to be too dependent on political groups”, explains a former member of Fakir, the newspaper founded by Ruffin.

A rich address book

If Olivier Legrain never pays the bill, it’s because he has many other things to offer than his wallet. “The left must also have powerful people who carry its program,” he confided to a visitor. He allows himself some advice on how to speak to leaders without frightening or denying himself. François Ruffin learned his lesson well and tried to put it into practice on September 7, 2023, in a private hotel in the chic 8th arrondissement of Paris made available to Ethic, the employers’ organization headed by Sophie de Menthon. In front of him, around forty entrepreneurs whom he jostles as much as he tries to lure: “Tomorrow we will have to build the country together, I am curious to see what is happening in France from above.” Legrain provides its extensive address book. There we find a host of leaders, glories of French industry yesterday and today, his friends Jean-Pierre Clamadieu, Henri Seydoux (Parrot) and Benoît Bazin (Saint-Gobain). To one of them, he whispered at the beginning of the year: “It would be good for you to meet François Ruffin but it is still too early. He has not yet matured his speech.”

In the bar in Neuilly-sur-Seine where he welcomes us, a stone’s throw from his home, Olivier Legrain sometimes smiles, sometimes grimaces. The next planned dinner with the nine oils of the left has been canceled. Some became angry upon learning of L’Express’s investigation, and feared reprisals from Jean-Luc Mélenchon and his Red Guards, who were increasingly brutal in their words against his rebels. The millionaire psychologist has never understood the violence of politics, helpless in the face of the banderillas constantly sent by rebels, socialists, ecologists and communists. The founder of Mediapart Edwy Plenel, who is one of his friends, had nevertheless warned him: “Stop wanting to save all the misery in the world, you cannot.”

.