Footnotes are what you don’t read. And even less when they are relegated to the end of the volume. They are meant to be addressed only to researchers.

It comes back to us that an essayist once devoted a whole study to them and that a novelist even concocted a whole book whose pages are exclusively made up of duly numbered footnotes without our knowing the text of which it stemmed. Of all the collections, the Pléiade is without a doubt the one that consumes the most. In some cases, they are so numerous that they impose a chaotic reading. We are not going to verify the veracity of the famous “Long time* I went to bed¹ early! Critics do not hesitate to mock their publishers, most often academic specialists in the work in question, suspected of wanting to rewrite it by extending it into endless variants discovered, oh joy! progress in literary genetics. In many cases this only ends up killing the grace of writing and, consequently, even the pleasure of reading. But when exceptions arise, we make a point of pointing them out. Thus the new two-volume edition of Novels by Louis-Ferdinand Céline published between 1932 and 1947. In all, 3,500 pages on Bible paper.

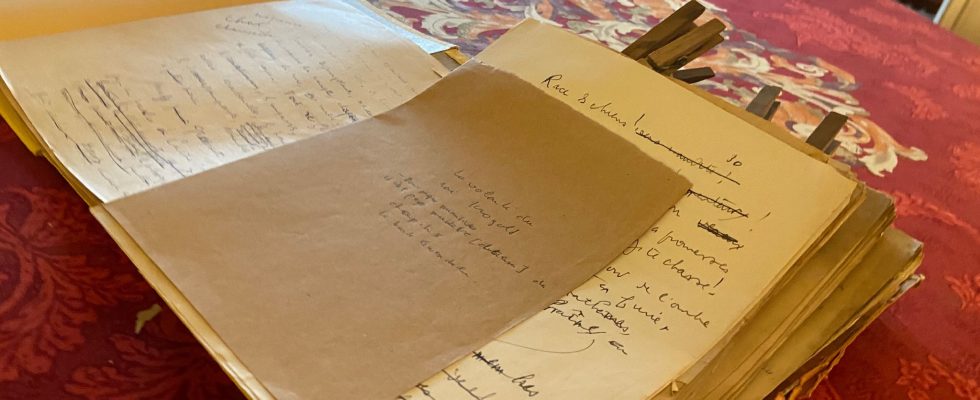

With unaccustomed celerity for a collection that borders on eternity, an infernal trio of eminent Celinians, Henri Godard in the lead with Pascal Fouché and Régis Tettamanzi, have worked hard to restore this block of fallen literature from the planet. Bardamu. There was urgency since the incredible exhumation in the summer of 2021 of thousands of unpublished pages, hoped for but not found since the Liberation. Not enough to reveal another Céline or enough to convince those who condemn him and refuse to read him, but ample enough to enrich our knowledge of his romantic genius and the Copernican revolution he wrought on the French language. In particular, it confirms the explicitly autobiographical dimension of the projected work, pushed to its climax by a mythomania and a paranoia that have not failed it. And this is where the famous footnotes, comments, prefaces and presentations, partly relegated to the end of the volume in view of their abundance, take on their full value. They are so finely detailed without drawing a line, so discreetly erudite without lapsing into scholarly cunning, that they form a novel within novels without overwhelming the reader already struck by the eruption of the Celinian volcano.

The pleasure of the text

All this paratext has the primary effect of taking us into the laboratory of the work in progress, among the test tubes of the mad scientist working out the improbable formulas which were to give, among other things, his masterpiece. Death on credit. We are immersed in the work of the language, the twists of the writing to make popular orality heard, the efforts to make the effort disappear towards an illusion of spontaneity. First drafts, trial and error, rewrites, erasures, remorse, come back to it. The author may be hostile to him, the reader does not get tired of it, the flavor of the comic compensating for the violence of the tone. Everything for style! And below, inside, behind, nothing less than a vision of the world.

To top it off, theAlbum Louis-Ferdinand Celine which follows this double is remarkable, certain documents and several photos, unpublished or little known, being strikingly true. We have rarely read/seen such a lively writer’s biography concentrate. The iconography is obviously no stranger to this, any more than the touch of Frédéric Vitoux (it is rare that a Album Pléiade demonstrates such writing skills). And even more, the proximity, the familiarity, the very intimacy with his universe. It is true that, from the beginning of the 1970s, he successively devoted a 3rd cycle thesis to the work, an essay on the cat and finally a biography on the life of Louis-Ferdinand Céline, in a time when this was hardly done. Enough to create lasting and fruitful links.

All this for what? For the pleasure of the text. Granted, but again when it reappears full of new trees? wonders ultimately Henri Godard, the architect of these two volumes of novels, to whom nothing that touches Celine is foreign. To reflect on the nature of literature and question its value. No more no less.

* Pierre Assouline is a writer and journalist, member of the Goncourt Academy