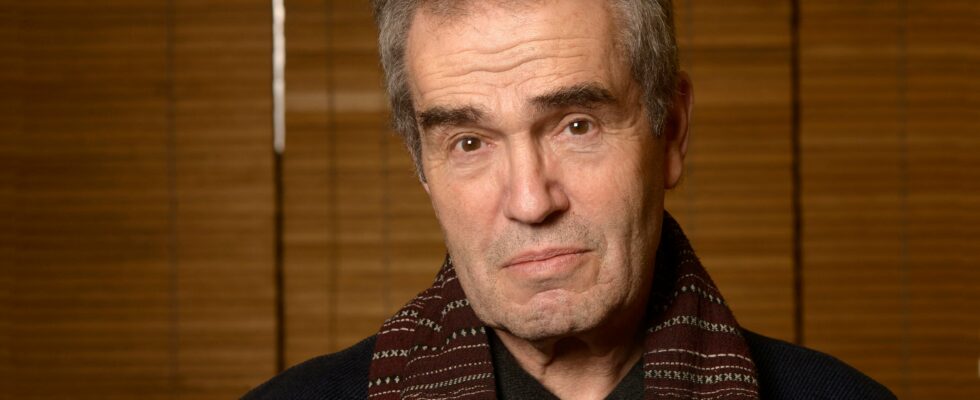

In highlight of Song of the books (Grasset), Gérard Guégan copied these two unstoppable sentences from La Fontaine: “Long works scare me. / Far from exhausting a material, / We must only take the flower.” While the boring cobbles of the next school year are already piling up on the desks of literary critics, this chiseled essay of only 135 pages provides real comfort: it can be sipped in an evening, like one savors an excellent whiskey with delight.

Born in Marseille in 1940, Gérard Guégan is nothing like an heir: a mother who was a home embroiderer, an unemployed communist father and an uncle, Marius, a “Leninist turfist”. We rarely slip a book into his hands. Self-taught, he developed a passion very early for the character of Julien Sorel, his “dream master of the moment”, as well as for Rimbaud. Does being from the same city as André Suarès and Antonin Artaud predispose you to being a hothead? The budding poet does not hesitate to “throw a fist” when the Jeune Nation activists come to “break some shit” at the end of his high school. Although brawling and insolent, he is detained by a teacher to go visit Giono in Manosque. Pipe au bec, the author of Hussar on the roof is amused by the young man’s “strong tongue”, gives him advice (lie as much as possible) and offers him a book (Refusal of obedience). Here is Guégan armed for a life where, both as an editor and as an author, he will never stop kicking in…

The Song of the Books is a sort of best of things seen and things heard by Guégan during his adventures in Paris and elsewhere – at 84, he is now based in Nîmes, the birthplace of Jean Paulhan, who, in 1964, had invited us not to think too much like Rimbaud. “Only imitate what you think you hate,” the master of The NRF. Here, Guégan does not act showy: he is content to transcribe, sometimes with playfulness, sometimes with melancholy, a few striking scenes. Here he is with his Marseille friend Jean-Jacques Schuhl making fun of Grand Meaulnes. Here he is facing Henry Miller who declares to him: “In short, you are trying to make me say what a novelist is? Well, he is a garbage collector. And, if he is not, it is a crook… Why a garbage collector? But because the novelist, the real one, goes looking for his subjects in the trash. Think about it, it’s in what humanity throws away and rejects that the secret of life is hidden. what we call life and it is this music of repression and fear that the writer-garbage collector makes visible.

“If you want to survive, you have to hide.”

A few pages later, we are in 1976, and Guégan breaks bread with someone who rarely thought of himself as a garbage collector: Philippe Sollers. At the time of Armagnac, Guégan urged Sollers to discover Bukowski and reread Hemingway. These two didn’t go together. Guégan then reports these juicy comments from “Buk”: “Hemingway, he cheated on everything. When he went for a walk to the front, he stayed there just long enough to pose for the photographer. Then, screw it, he came back hide in his palace. Wherever he went, a crate of champagne bottles followed him. Perhaps he had shot animals in Africa, but in Spain or the Ardennes, he must not have pressed the button. relaxation only by mistake… It relaxes you, eh, the Frenchie? But writers who talk about courage are cowards. Think about it, you have to survive to be able to type on the keyboard of your machine. You have to hide.”

American authors obviously liked to tell Guégan to “think”… He spent a large part of his days having fun, chatting with ex-con Alphonse Boudard, and even interviewing Florence Delay. Page 100, we learn that Jean-Pierre Martinet wanted to adapt The Idiot, with Georges Perec in the role of Prince Mychkine. Martinet whose novel Guégan had published Jerome in 1978: “The established literary critics mostly turned away from this book. Insults were exchanged, bad manners abounded, slaps too, but we lost the battle.” When he toasted with Michel Mohrt, the latter mocked the painful Faulkner and praised Kerouac, who “laughed at everything, didn’t pontificate.” Perhaps everything wasn’t better before, but the world of letters was certainly more fun in Gérard Guégan’s time.

The Song of the Books, by Gérard Guégan. Grasset, 135 p., €16.

.