As a young journalist, I came to the Chancellery to interview Robert Badinter on a reform underway when he was Minister of Justice. It was our first meeting. Dazzled by this man who had fought so hard against the death penalty to end up abolishing it, I asked him my questions to which he responded with concentrated severity. The newspaper asked me to stick to the slimming diet: three pages, no more. When I submitted to the minister the remarks that I faithfully attributed to him, he sent them back to me on thirteen sheets, scratched with an annoyed pen. It was too long, the article was scrapped due to lack of space. I remembered that Robert Badinter had nothing but contempt for posturing, superficiality, approximations and… summaries.

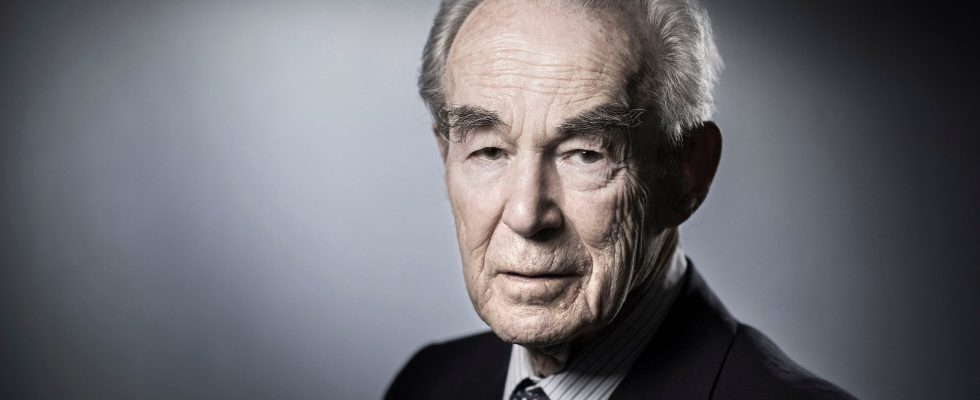

My last meeting with Robert Badinter was last summer. With the steps of an elegant old gentleman, he led me to his office, facing the Luxembourg Gardens. The tea was ready. Extremely courteous, he floated on his memories with mischievous pleasure. I was waiting for him to tell me how, as a young lawyer during the Algerian war, he had defended L’Express against the multiple attempts by those in power to muzzle him while the newspaper denounced exceptional legislation and the horrors of torture. , violations of freedoms. He was kind enough to mention the multiple seizures of which the newspaper had been the subject, the indignation which they aroused in the Mendès France camp, and the subtle game in which Françoise Giroud engaged in examining the articles before their publication and “extirpating” them. judicial venom while retaining political venom.”

But I felt that he didn’t really want to talk about himself or his achievements as a tenor of the bar. It wasn’t his subject. I didn’t wait long. He burned to talk about Servan-Schreiber, “this exceptional man, so courageous”, the founder of the newspaper. “Jean-Jacques was the biggest repeat offender I have known, knowing the number of convictions he incurred as a writer and boss of L’Express. » In his mouth, it was a compliment. I felt moved to resurrect this man who fascinated him with his audacity, his aplomb, his insatiable ambition. Suddenly, without losing the amused look he cast on the past, Robert Badinter sat back in his chair, then leaned over. And I understood then that he was having trouble forgiving his ex-friend Jean-Jacques, who had disappeared for a long time, for the mistake where hubris led him. Having become a deputy and president of the radical party, JJSS went on a political campaign at the risk of damaging their common ideal, support for Mendès France, for a rigorous left and right. It was a betrayal.

As day fell outside the window, Robert Badinter did not stoop to pronouncing this word, which was too loaded with aggression. With this way he had of wrapping himself in the law and the facts to judge the human comedy, he simply observed: “L’Express was born from the desire to bring Pierre Mendès France to power, and not to offer a tribune from the pen of a man. » Choosing oneself at the expense of the collective was at least a lack of taste in the eyes of Robert Badinter.

.