He remains a master of abstract expressionism across the Atlantic, the one who makes hairs stand on end with his rectangular canvases with intense colors and delicate contours. As much an artist as an intellectual brewer of ideas and emotions, Mark Rothko, born Rotkovics in Dvinsk, in the Russian Empire – today Daugavpils in Latvia -, is on display this fall and until April 2 in the Louis Vuitton Foundation, which is dedicating the first retrospective to him in France since that of 1999 at the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris. In other words, one of the events of the artistic season, with 115 works from the largest institutional or private collections on the planet. Christopher Rothko was only six and a half years old when his father killed himself on February 25, 1970 in his New York studio. Psychologist, author of around twenty essays on his father’s work, he is also at the origin of the posthumous edition of Mark Rothko’s unfinished work, The Reality of the artist, written during the 1940s. Curator of the exhibition alongside Suzanne Pagé, artistic director of the Foundation, he gives us his insight into the creative process of the emblematic painter.

L’Express: Mark Rothko’s only self-portrait, dated 1936, remains enigmatic. What does this painting tell us about the artist?

Christopher Rothko: He tells us as little as possible. Except he wants to be taken seriously. He hides behind dark glasses, doesn’t look at us or consider us at all. Even at this stage of his career – the figurative period of his beginnings – he doesn’t want people to look at him, he wants people to look at his paintings. It should be noted, however, that in the choice of colors and posture, Rothko clearly intends to recall his dear Rembrandt, the greatest master of self-portraiture.

In the 1940s, Rothko went through several aesthetic phases in less than ten years: mythological, surrealist, then the turn towards abstraction with the “multiforms”. Would you say that it is an intense period of search for meaning?

Absolutely ! In fact, we have the last vestiges of his figurative period at the beginning of the decade and the realization of his signature at its end. So this is truly a decade of change, punctuated by his book of philosophical writings, which also moved his process forward. My father’s entire career was marked by the search for an artistic language that would speak universally and directly to our inner self. What we see in the 1940s is the continued development of this language – and some fabulous paintings that demonstrate its progress.

Mark Rothko, “Slow Swirl and the Edge of the Sea”, 1944.

/ © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko – Adagp, Paris, 2023

From 1949, he shifted into absolute abstraction with his Color Fields rectangular in shape with ocher, yellow, red, blue tones… What was he expressing by his refusal to be seen as a “colorist”? The search, above all, for an emotional impact on the spectator?

We can see that when Rothko moves from his totally abstract multiform phase to his Color Fields so-called classics, it is not its chromatic palette that changes. These rich, saturated colors are already there. What changes is the simplification and clarification of the form, and with it the amplification of its message. Of course, the artist was not a formalist either. For him, the medium was not the message. It was a way of expressing, as directly as possible, his understanding of the human condition, with all its emotional complexity.

Mark Rothko, “The Ocher (Ochre, Red on Red)”, 1954.

/ © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko – Adagp, Paris, 2023

Your father said that he wanted to “elevate painting to the same level of intensity as music and poetry”. As a child, you shared great moments with him around Mozart and Schubert. What was his relationship to music?

I believe my father saw music as the most direct way to access our emotions, as the ultimate way to express the inexpressible. He sought this same type of fully experiential interaction with the viewers of his work – a type of painting that would, at least initially, bypass our intellectual processes and enter directly into our emotional world. Is there something that makes you cry, that pulls on the memory, that moves the mind to the same degree as music? My father hopes we will answer: “A painting by Rothko.”

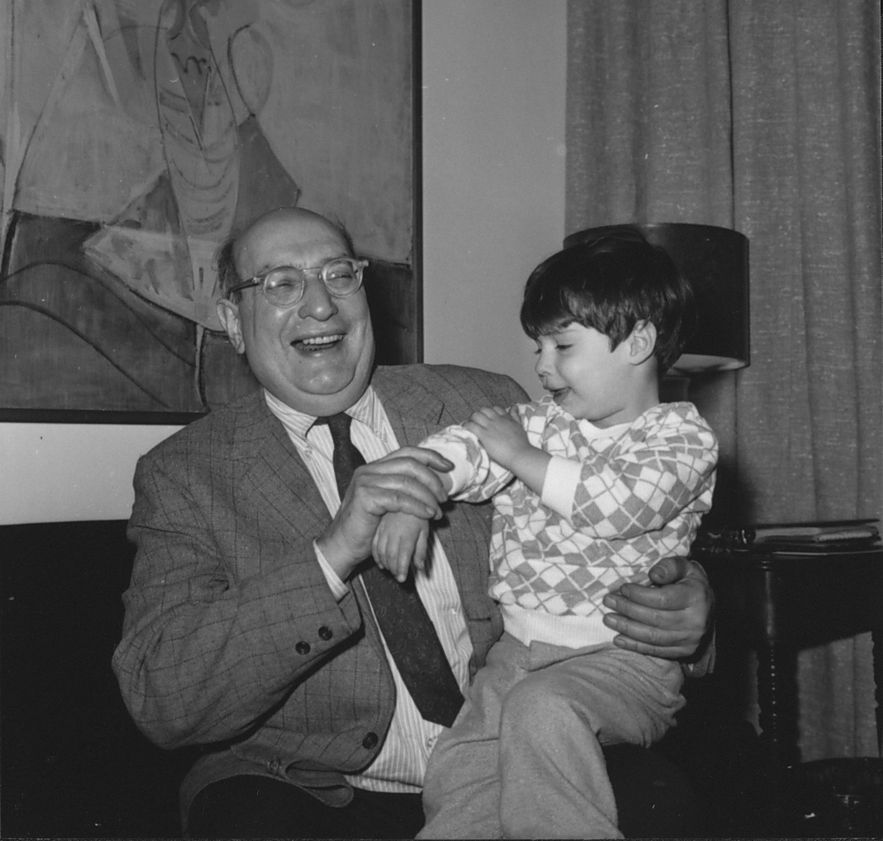

Mark Rothko and his son Christopher in 1966.

/ © Courtesy The Rothko Family Archive

“His painting has always been and always had to remain a matter of ideas,” you said yourself. How was this intellectual posture, this permanent questioning, expressed?

I’ve talked a lot about emotion, but I believe that even emotion was not the goal my father had in mind. It was a path to an exchange of ideas between art and viewer, or even between artist and viewer. These ideas are not always conscious, they are part of our deeper sense of what it means to be human. For Rothko, it was imperative to divert our attention from everyday life to the most essential and perpetual questions of our existence.

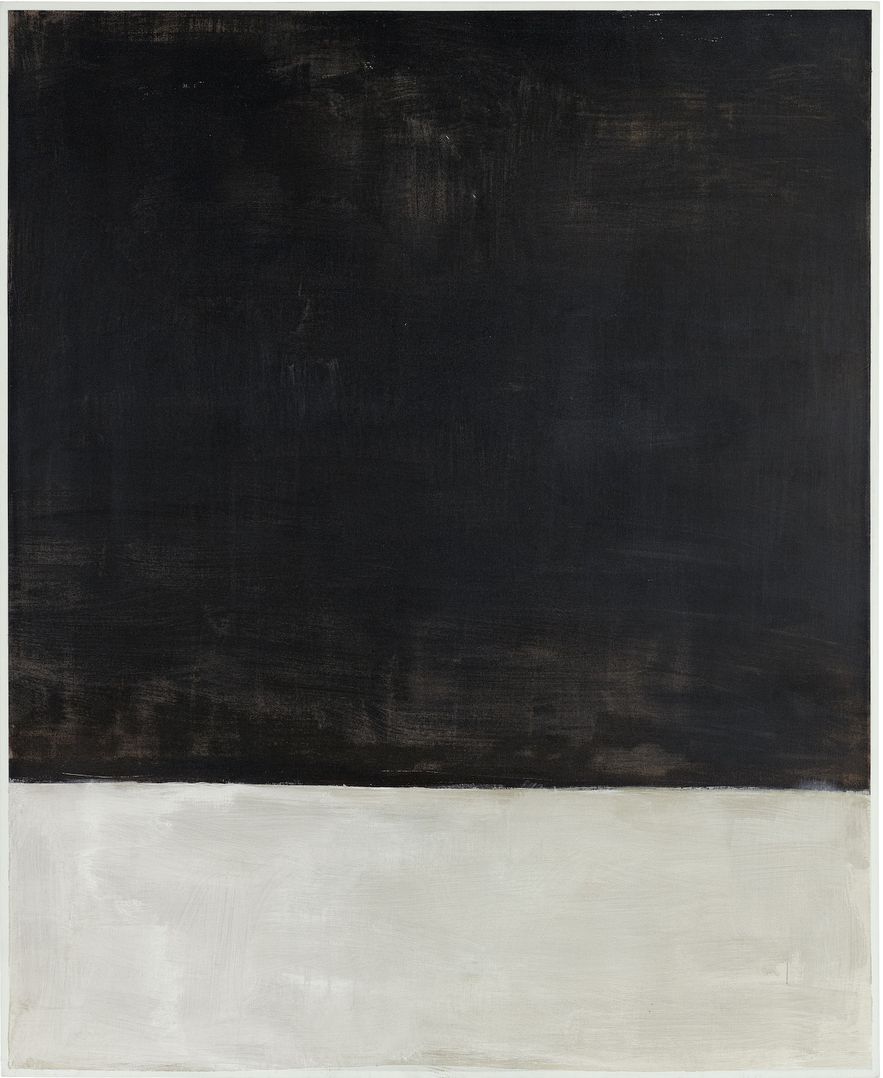

Mark Rothko, “Untiled (Black on Gray)”, 1969.

/ © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko – Adagp, Paris, 2023

The series of Black on Gray of the artist’s last years to the idea of depression, in some way announcing his suicide. A theory that this retrospective, in particular, calls into question. What is your feeling on this?

In fact, my father’s color palette darkened more than ten years before the black and gray series. Rather than an indicator of mood, this change in color is a shift in Rothko’s strategy to attract the attention of those viewing his paintings. Instead of capturing their attention, he slows down the process of interaction, using colors and a simplified formal structure that envelop the viewer and slowly seep into their consciousness. He knew he risked losing some of those who were drawn to his brighter colors, but he was willing to make that sacrifice knowing he would have a longer, deeper conversation with those who remained. The series of Black on Gray from 1969 was painted when he was very depressed, but it was also the period when he produced the greatest number of paintings of his entire career. These works are in no way a sign of resignation: they constitute a new beginning and are filled with tremendous energy.