The footage of the police killing of Tire Nichols in Memphis is unbearable. The relentlessness is as palpable there as the insensitivity for human life. The police officers of the Scorpion group, supposed to fight the rampant insecurity, left him to die, and the helpers who arrived late on the scene did no better. Three days later, the 29-year-old who just wanted to go to his mother died of hemorrhage, kidney failure and cerebral edema. According to CCTV footage, he hadn’t even committed a traffic violation. Violence was deployed against him without convincing reason.

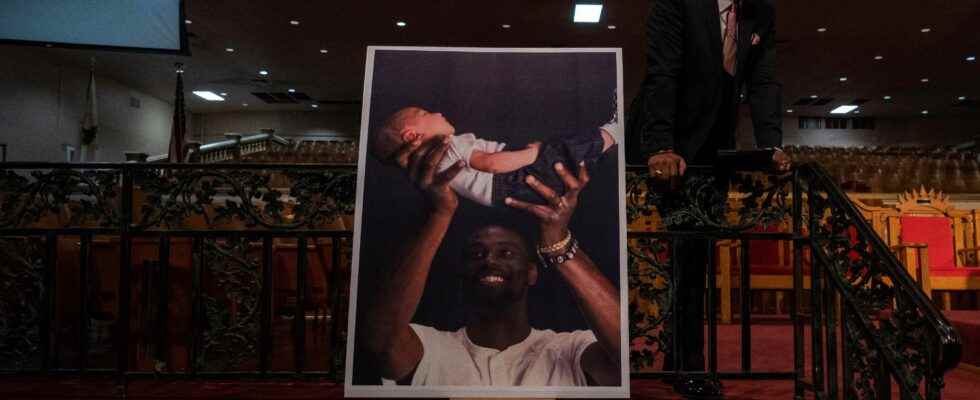

Tire Nichols was African American, as were the five police officers who knowingly killed him. In a city where 58% of the police are made up of African-Americans, the young father of the family had every chance of dying under the blows of African-American police forces. Could this tragic event be an opportunity to reflect on violence in the United States instead of hiding behind the question of race, which is much more sold?

Several days after the indictment of the five police officers guilty of murder, we learned of the dismissal of a white policeman who had participated in the massacre. Quickly, the family of Tire Nichols and many commentators implied that the white policeman had been protected, because white. The Memphis police commissioner, who is black, had however quickly reacted: “This case contradicts the idea that the issues and problems of policing are linked to race. It is about human dignity and integrity, responsibility and duty to protect our community. So that takes race out of the conversation.” Nothing to do, the debates continue to rage in the United States: are black police officers racist, or not?

In a country where the question of race is omnipresent, it is logical to wonder to what extent racism slips on at the same time as the uniform. But, on the one hand, this implies that blacks are incapable of thinking for themselves, that they are under the infusion of dominant racist thought, under white control in a way. This is thus to deny them the possibility of their responsibility, which amounts to infantilizing them and recalls the dominant discourse of the time of slavery: Blacks are big children. What never ceases to amaze me in the new anti-racism remains this blind stubbornness in mirroring racist discourse. On the other hand, blaming everything on race obliterates the much-needed debate about police training and arms proliferation.

Disarm not the police, but the Americans

In the United States, 15,000 police departments form an incoherent layer cake, especially since the training is provided by the military without learning de-escalation doctrines. And even if the police were completely reformed, trained to avoid pulling out a weapon all the time, the proliferation of weapons makes each arrest potentially deadly. According to the Washington Post, between 2015 and 2022, US police killed 8,079 people (including 1,895 black people), an average of 1,150 per year. But there are, on average, 8,500 victims of homicide per year (excluding those killed by the police) and more than 20,000 injured.

In a country where 265 to 350 million firearms are said to be in circulation, it seems logical that 83% of those killed by the police were armed. These numbers are staggering. Add to this already gloomy picture the bad reputation of the police, largely maintained by activists and the media, who struggle to recruit and who end up accepting candidates who do not have the shoulders to manage situations where human life is at stake. Summarizing heinous murders like that of Tire Nichols to the question of race further removes the possibility of decisive political choices to disarm not the police, but the Americans.

To reduce everything to race amounts to erasing the singularity of each and to proposing a simplistic reading grid that does not solve any problem but maintains artificial borders between men. In white dog, as students throw cobblestones in 1968, Romain Gary comes across a black student writing a novel about Petrarch and Laure. “No, not a Laura and Petrarch black : the real ones, the historical ones… I guess I’m a reactionary,” he says to Gary, who sighs with relief. “A brother, I tell you. A brother of race. I recognize in him that sacred spark of terrorism that excludes no one.”