Mohamed Ibrahim Moalimu, who had survived four suicide attacks before, was targeted in a suicide attack on Sunday in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia.

BBC World Service Africa Editor Mary Harper wrote about why Moalimu, the Government Spokesperson and former BBC Somali Correspondent, continues to live in a city ravaged by violence.

On my phone, I have a list of required information. At the top, over my passport number and bank account details, is Moalimu’s name, number 16.5, and the words “She loves blue patterns and white.”

These are the shirt size and preferred colors of my dear friend Mohamed Ibrahim Moalimu, who previously worked as a BBC Somali Correspondent.

Whenever I go to Mogadishu, I buy shirts for Moalimu.

I like to go to Jermyn Street in London, where the high society men buy their suits. I scrutinize dozens of colors, patterns and designs to find the exact one.

In fact, on my next trip to Somalia, I also had two shirts waiting in my luggage.

The problem was that Moalimu was not in Mogadishu. He is being treated in a hospital in Turkey.

A small ambulance was transported by plane. It was not easy to lift the stretcher on which he was lying on the small plane and place it on the plane.

Moalimu was caught in the fifth suicide attack on Sunday. This time the target was directly himself.

When a suicide bomber reached Moalimu’s seat, he rushed to his car and detonated the explosives on him.

Little was left of the attacker. His car had been wrecked.

I couldn’t understand how Moalimu survived. His leg was broken and he had injuries to his chest and elsewhere, but he was conscious and understandable.

refused to go

If you meet Moalimu, the first thing you will probably notice is the terrible scars on his face. These are from the second suicide attack in 2016.

He was at his favorite restaurant by the sea. The militants of the radical Islamist organization Al-Shabab attacked the restaurant from the beach and besieged it for hours.

Moalimu was saved by lying down and pretending to be dead.

He described how militants kicked people’s corpses and shot the scared to make sure they were dead.

He was treated for months in Somalia, Kenya and England. Mainly, there was concern in his eyes.

It is difficult to identify Moalimu’s character with this dangerous world in which he lived and refused to leave.

He is a kind, soft-spoken and calm man.

Mogadishu and most people living in the city are hectic, loud and nervous. This is hardly surprising, as the city has been at war for more than 30 years.

I was in Mogadishu when Moalimu was not caught in his first suicide attack.

In June 2013, when al-Shabaab militants entered the United Nations building and spent an hour inside, killing as many people as possible.

Coincidentally, Moalimu was passing by in his vehicle at the time of the attack. The remnants of the suicide attacker fell on his car and broke its windshield.

He showed me his shattered windshield with his familiar, gentle and unpretentious demeanor. He took out a terrifying photo of his vehicle, taken right after the attack.

He asked me if the BBC would pay for the windshield.

After all, he was on duty when it happened. As he often did, he covered the violence in his hometown.

It would not have been possible for the BBC to process Somalia in this way without people like Moalimu.

He is now the spokesman for the government. But while working at the BBC and passing his news, Moalimu was always ready to tell people exactly what had happened.

Even today, whenever I call, he starts with a list of what happened that day. Assassinations, explosions and political struggle.

He even does this when I call to ask him what shirts he wants me to bring.

Unsung heroes of journalism

When Moalimu was a colleague at the BBC, he was the first of two people I called before I went to Somalia.

If Moalimu said, “Don’t come,” I wouldn’t go, even if things seemed calm. If Moalimu said “Come”, I would go even though the security situation seemed risky.

To Moalimu I entrusted my life. He was one of the unsung heroes of my profession.

With so many contributors, I find it hard to understand why journalism is associated with a famous and brave reporter.

Producers, cameramen, sound actors, and perhaps most importantly, local journalists, sometimes described as “the host”, who know everything and on whom the team is completely dependent.

Moalimu was one of these people, as was many other Somali journalists I work with, who risk their lives every day.

– – – – – –

– – – – – –

After quitting journalism, I said how disappointed I was that he was a government spokesperson.

How could such a brave journalist get to “the other side”?

As always, his answer was measured:

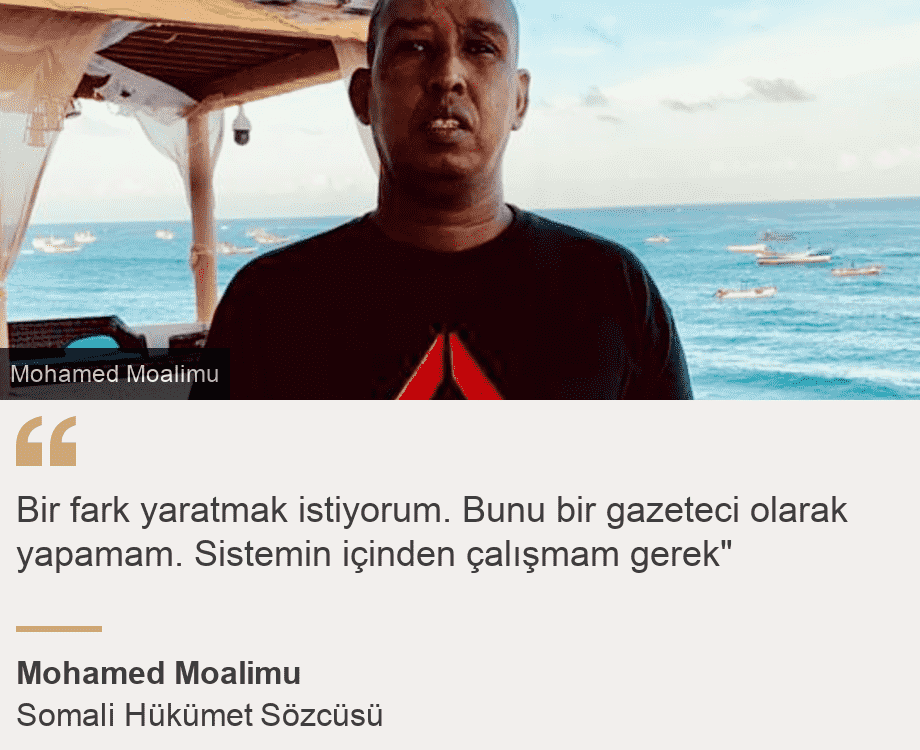

“I want to make a difference. As a journalist, I couldn’t do that. I have to work inside the system. I want to be a parliamentarian and this is my first step.”

After taking on his new role, I had to develop a more formal relationship with him.

Their shirts have also become official. Now they’re starched and white so that she can wear them under stylish suits.

But whenever I walk down Jermyn Street, I will remember the joy I had in choosing colors and patterns to match its calm and gentle character.