Tunisia is set to become the epicenter of a migration crisis in the central Mediterranean, the deadliest route in the world with nearly 1,800 dead since last January, according to the United Nations. While the tragedies multiply this summer with, again on August 8, the death of 41 people including three children, off Lampedusa, in the sinking of their boat from the coastal city of Sfax, the photo of the lifeless bodies of two migrant women from sub-Saharan Africa, Fati and his daughter, Marie, 6, shocked the whole world. They were found dead of thirst in the Libyan desert after being abused and then abandoned by the Tunisian authorities.

If Tunisia has just signed, in July, a “strategic partnership” with the EU centered on the fight against irregular immigration, its president, Kaïs Saïed, develops an openly xenophobic rhetoric against migrants. To make people forget that today, among the many candidates to leave, there are many Tunisians who no longer believe in the future of their country, explains Vincent Geisser, researcher at the CNRS and the Institute for Research and studies on the Arab and Muslim worlds (Iremam).

L’Express: How do you explain that Tunisia has become the main gateway to Europe for migrants?

Vincent Geisser: There is an obvious geographical aspect, as Tunisia is close to the island of Lampedusa, in Italy. But there is another very important structural factor: the country has a relatively old African immigration. Men and women who have jobs as security guards, in tourism, services… Until recently, these immigrants served as a reception base for other Africans in an irregular situation. They said to themselves that if ever they were unable to pass through Tunisia, at least here they could survive. Over time, Tunisia as a migratory route has become a rather reassuring axis, reassuring for migrants who knew that, in any case, they were not going to be left completely on their own.

How has President Kaïs Saïed’s anti-migrant rhetoric changed everything?

The President of the Republic, in a speech given on February 21, squarely called for the hunt for migrants and to get rid of those who threatened Tunisia in its Tunisian and Arab-Muslim identity. Result: migrants are no longer safe in Tunisia, with a part of the population which, today, does not hesitate to attack them physically, as we saw recently in Sfax, when dozens of sub-Saharans were assaulted and chased out of town. This policy of lynching, of pogrom, is still quite new. All this under the watchful eye of the police, who do not intervene to protect them… Those who embark at sea from Tunisian ports know that they no longer have a future in Tunisia.

Tunisia’s president said there was a “criminal plan to change the composition of the demographic landscape” of the country. Why this conspiratorial rhetoric?

His speech clearly refers to the “great replacement” speech. Moreover, Eric Zemmour was one of the first to congratulate him. There is a theory circulating in Tunisia that some countries are working to make Tunisia a country of invasion. For some opponents of Kaïs Saïed, Wagner and Russia are behind it all… And, for Saïed’s supporters, this “invasion” would be the Machiavellian plan of certain countries that want to harm his regime… In short, conspiracy. But, more broadly, within Tunisian society, such a feminist militant is denounced because she is allegedly financed by the invisible hand of Europe; such a democrat by saying that his ideology is imported by people who wish harm to the country; the Islamists by accusing them of being in the pay of Qatar…

There is an anti-foreign, very anti-Western discourse, which can make one think somewhat paradoxically of what we hear today in the Sahel, especially in Niger. With also behind, in a less explicit way, the idea that these migrants are Christians and that the risk of the establishment of churches exists. Today, in Tunisia, ohn even speaks of African colonization… in an African country!

The photo of the corpses of Fati and his daughter, Marie, has shed light on the brutal operations of expulsions and abandonments in the desert. What do we know about the extent of what some NGOs call deportations?

We are talking about dozens of people who would have lost their lives in the desert, but it is very difficult to quantify the phenomenon. Tunisian authorities have denied expelling migrants to desert areas, condemning them to near certain death. There was a counter-expertise, in particular from the UN, and the work of several Italian media which made it possible, in particular through satellite images, to show that there were many people who had been sent to the desert. . It is a deportation in the strict sense.

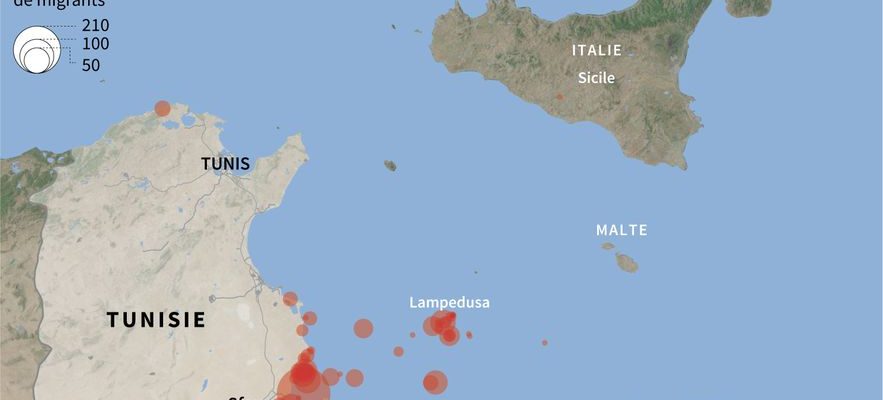

Shipwrecks off Tunisia in 2023.

© / AFP

And Tunisia is doing everything to hide these facts…

Despite everything, Tunisia is not Gaddafi’s Libya. So, from this point of view, Tunisian society, including the supporters of President Saïed, is not ready to assume the image that was that of a Gaddafi “man-eater”. Tunisia remains marked by ten years of democratic experience, with competent administrative elites and a concern to preserve the image of an open and tolerant country. For these reasons, the Tunisian authorities tend to deny the facts of which they are accused.

Secondly, there is a Tunisian social and economic reality which means that the country needs funding. The president may have an anti-IMF, anti-World Bank speech and want to show that he defends the sovereignty of the Tunisian people against the West, it remains dependent. This European agreement on migration issues is a matter of survival, Tunisia has still not obtained an IMF loan. For the first time, we are seeing shortages that never existed. Today, in Tunisia, if you want to give a gift, you are told to bring flour, coffee and bread…

Tunisia, strangled by a debt equivalent to 80% of its GDP, is plunged into a financial and liquidity crisis which has worsened in recent months. And an unprecedented social crisis with high inflation. Paradoxically in relation to the president’s speech, hasn’t Tunisian emigration accelerated?

Many crossings had already taken place under Ben Ali. At the time, there were several thousand young people who left Tunisian ports every month to come to Europe, via the island of Lampedusa. It continued after the revolution and even amplified. Even if it is very difficult to have reliable figures, today there are very large flows of young Tunisian migrants, mainly men, but also more and more women, some are unemployed and saving to emigrate. There are also, in the middle class, university professors, journalists who objectively want to leave Tunisia.

In the recently signed agreement with the European Union, there is a double lie. That of the Tunisian state, which speaks of sub-Saharan migrants so as not to mention the problem of its own migrants. Saïed is embarrassed to see his own nationals leaving. And that of the European Union, with an agreement that will not necessarily be applicable due to the disorganization of the security apparatus and Tunisian institutions.

Tunisians try to reach Europe by crossing the Mediterranean on August 10, 2023.

© / AFP

Have the recent political changes in the Maghreb modified the migratory balances?

Countries like Algeria, and its president, Abdelmadjid Tebboune [NDLR : en fonction depuis 2019], now have increasingly secure policies. These finally push migrants to find other countries, as a place of quick passage. There is a sort of migratory individualism in the Maghreb countries, a lack of solidarity which tends to push States to send migrants back to neighboring countries.

Tunisia and Libya announced on Thursday, August 10, that they had agreed to share the reception of sub-Saharan migrants, some of whom have been stranded for a month near the Ras Jedir border post. What is the Tunisian strategy?

At the time of Gaddafi, Libya had become a country of passage for African populations, with a very ambivalent policy which consisted, on the one hand, in opening its door to sub-Saharan migrants, and on the other, in practices almost slavers. Today, Libyan political instability, insecurity and often mistreatment have prompted migrants to fall back on Tunisia…

What the Tunisians want by signing this agreement is a stability of this border, because there are very strong regionalist interests. Part of the Tunisian economy is fueled by informal trade. Today, 1 in 3 jobs is in the “grey” sector and part of the illegal sector is closely linked to cross-border trafficking. So having good relations with the Libyan authorities, be it the pro-Istanbul clan of Abdel Hamid Dbeibah [l’actuel Premier ministre] or the pro-Haftar clan [le général Khalifa Haftar, candidat à la prochaine présidentielle], in the east of the country, provides economic opportunities for the populations of southern Tunisia. Border traffic between Libya and Tunisia allows entire regions to survive. If good understanding with Libya also involves the fight against jihadism on both sides of the border, the mutual interests are above all economic.

Many observers point out that the “Balkan route” [via la Turquie] is today very borrowed by the Tunisians themselves. For what ?

The Balkan route already existed at the time of Ben Ali. It is very popular, because visas are easier to obtain in these countries, especially Turkey and the countries of Central Europe. It is the policy of the “small migratory leap”, because their objective is mainly to arrive rather in Western Europe, even in Great Britain for some. Today, even though most of the Balkan States, under the impetus of the EU, are adopting increasingly restrictive migratory policies, this nevertheless offers a less risky outlet for the sectors than crossing the Mediterranean.