A “cemetery for children”. Three times more migrants have died or disappeared this summer while trying to cross the Mediterranean, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) alerted this Friday, September 29, while diplomatic negotiations are currently underway in Europe on this issue. Between June and August, at least 990 people were shipwrecked in the central Mediterranean, known to be the world’s most dangerous shipping route linking North Africa to Europe. This is three times more than the 334 migrants who lost their lives over the same period in 2022, according to a count by the UN children’s agency.

If the total share of children is not quantified (UNICEF recorded around ten per week in July), we know that 11,600 “unaccompanied minors” attempted to go to Italy between January and mid-September 2023 on board makeshift boats. This represents 60% more than over the same period last year (7,200). “The tragic toll of children dying in search of asylum and safety in Europe is the result of choices policies and a failing migration system”, estimated Regina De Dominicis, who coordinates the subject at Unicef.

In total, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees summarized Thursday during a meeting of the Security Council devoted to the crisis in the Mediterranean, this brings to more than 2,500 migrants dead or missing between January 1 and on September 24, 2023, an increase of 50% year-on-year.

Migration policies are toughening in Italy

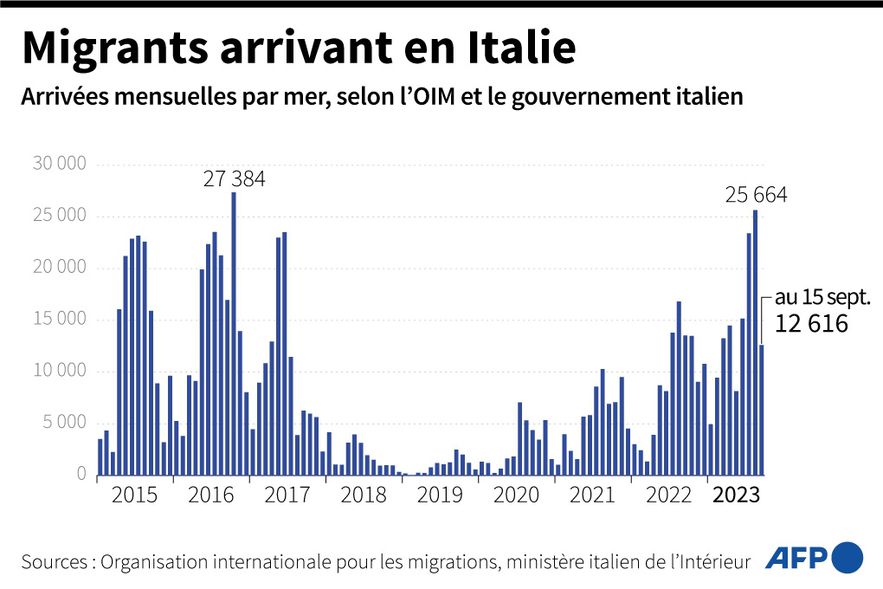

The spectacular images of the arrivals of boats in mid-September on the small Italian island of Lampedusa have put the burning issue of European cooperation in the management of migratory flows back on the table. With 8,500 people who landed on the island in three days, more than its total population, the arrivals sparked a local crisis in Lampedusa and a political storm in Italy, which has been increasing emergency and firm measures ever since.

Latest example to date: the Italian government of Giorgia Meloni, at the head of a right-wing and far-right coalition, approved Wednesday evening in the Council of Ministers a draft decree which opens the possibility of placing unaccompanied minors in over 16 years in adult structures and to have them undergo medical examinations to determine their age.

If the project must still be approved by Parliament, where the ultra-conservative government has an absolute majority, the text authorizes “anthropometric measurements” and examinations such as x-rays to determine the age of young migrants. Objective: “It will no longer be possible to lie about your true age” to avoid possible expulsion, warned Giorgia Meloni on her Facebook page. A “worrying” provision, the spokesperson for Unicef in Italy, Andrea Iacomini, expressed alarm to AFP.

One in two refugees in the world comes from Syria, Ukraine or Afghanistan

© / The Express

War, violence and poverty

On the European scene, the situation in the Mediterranean has relaunched discussions in Brussels around the migration pact. The debates have been bogged down in disagreements since its presentation in 2020 by the European Commission. The European reform project provides, for example, for a strengthening of external borders or even a solidarity mechanism between the Twenty-Seven in the care of asylum seekers.

The leaders of the nine Mediterranean countries of the EU are still due to meet this Friday, September 29 in Malta to agree on their positions on this issue. “The adoption of a European-wide response to support children and families” is “absolutely necessary to prevent more children from suffering,” continued Regina De Dominicis of Unicef.

Migrants arriving in Italy

© / afp.com/Sylvie HUSSON, Sabrina BLANCHARD

According to the UN agency, it is “war, conflicts, violence and poverty” that push children “to flee their country of origin alone”. After the risks of “exploitation and abuse at every stage” of exile, of shipwreck at sea, those who reach European shores are first “detained” in centers before being transferred to shelter structures. reception “generally closed”, deplores Unicef. The agency counts 21,700 unaccompanied children in these centers in Italy, compared to 17,700 a year ago.