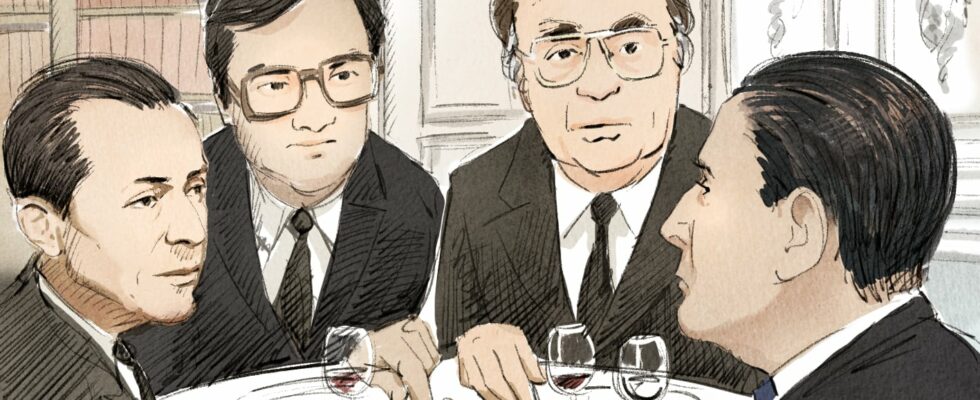

It was a time when you only had to sit down to a table to find a Prime Minister. There were four of them. Four men in a library. Emmanuel Macron often evokes the story of this meal, an emblem of another time, a symbol of practices and feelings that we believe are outdated and which nevertheless refer to what human nature and the exercise of power are. On May 10, 1988, François Mitterrand was “God”, according to the cartoonists of the time. After the Socialists had been defeated in the legislative elections two years earlier, he used the first cohabitation in the history of the Fifth Republic to do a backflip – which is not very reasonable at his age, 71 – and be re-elected president with 54% of the vote against his Prime Minister Jacques Chirac. The second round took place forty-eight hours ago. This Tuesday, the country is waiting to know the name of its Prime Minister. So we look at the images, Mitterrand coming down the steps of the Elysée Palace, getting into a car around noon to go and thank the little hands of his campaign; then Jacques Chirac arriving at 3:30 p.m. to hand in his resignation.

The most interesting part happens between the two sequences, away from the cameras. The guests received a phone call from the presidency in the morning: come and have lunch! Michel Rocard, who would have so much wanted to run for president to the point of having announced it and then backed out, would not want to see the dishes go by. Pierre Bérégovoy, former secretary general of the Elysée at the very beginning of the Mitterrand adventure, has an appetite, who would so much like to move from the shadows to the light, according to the expression immortalized by Jack Lang in 1981. Both dream of becoming Prime Minister, but by definition the position is not shared. Jean-Louis Bianco is the third man, in a more vague role, both collaborator of the head of state (he has been the secretary general since 1982) and potential surprise. Whether he is a simple witness or an actor, he himself does not fully know.

The meal around François Mitterrand begins without us really knowing what is at stake. Matignon is on everyone’s mind, but on no one’s lips. The head of state prefers to first discuss the second round of the election and the consequences that must be drawn from it. The guests agree that an immediate dissolution of the National Assembly is necessary, to send the right back into opposition. The presidential candidate did not commit to this point in his campaign, remaining vague about his intentions. Then the subject of New Caledonia is discussed: the archipelago is in the grip of enormous tensions, a hostage-taking in Ouvéa left 21 dead in the previous days, the issue will be at the top of the pile for the next government.

Vice is a dish best served sweet. You have to wait for dessert for the elephant in the room to make itself heard. Mitterrand “played with the nerves” of his guests, recalls Jean-Louis Bianco. Jacques Attali reports the presidential remarks in Verbatim: “I have one decision left to make: I must appoint a Prime Minister. One of the strengths of socialism in France is that it has many people of quality and talent in its ranks. I must say that in my eyes, the talents of each are equivalent. But there are de facto situations, and Michel Rocard has a slight head start.” Message received: he had barely returned to his car when the latter called Jean-Paul Huchon to tell him that he would be his chief of staff at Matignon. Four coffees and the bill? At the Elysée, no one paid, but it was Rocard who took the hit. Jacques Attali wrote: “The president confided to me shortly afterwards: Rocard had neither the skills nor the character for this position. But since the French people wanted him, they would have him. On the other hand, I would be the one to form the government.” For his part, Pierre Bérégovoy was taking the hit. “He really believed in his chances, in his body language you can see the disappointment,” says Bianco.

François Mitterrand had decided on the name of his Prime Minister before the meal, even though he had not said anything to anyone at the Élysée. When he speaks of these feasts, a monument of incomparable perversity, Emmanuel Macron always concludes with the same sentence: “It was another era.” As if court games had ended with the 20th century.

.