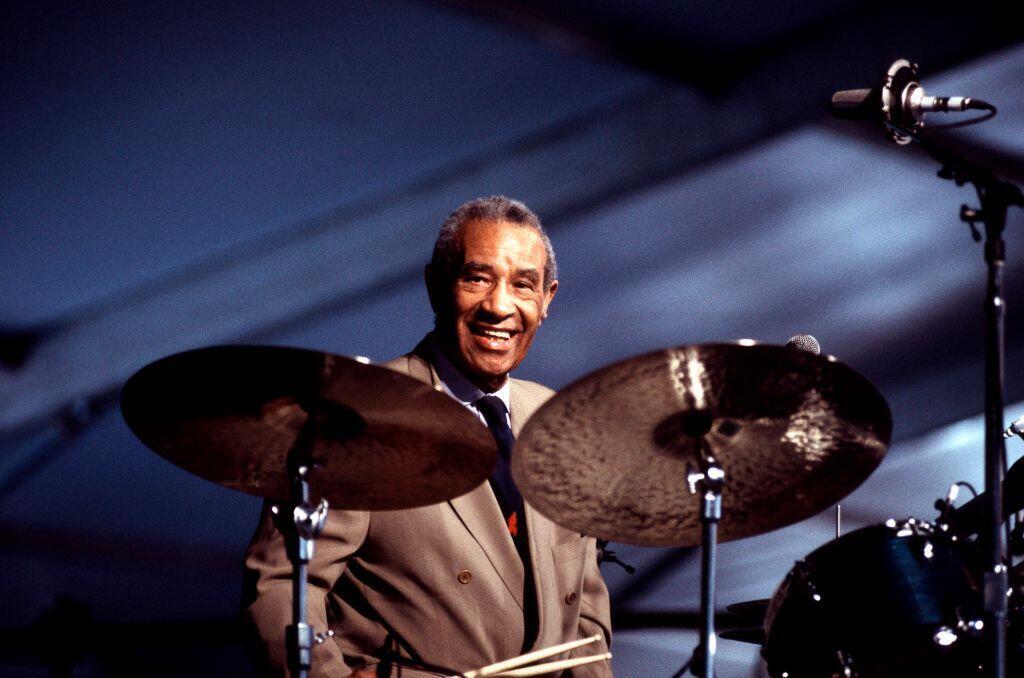

To realize the importance of Max Roach in “The Epic of Black Music”, it is enough to cite the musicians with whom he wrote great chapters in the history of jazz. This incredible drummer shared the stage or worked in the studio with Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, Charles Mingus, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins, Clifford Brown… In other words, the pioneers of ancestral swing.

This proximity to the great figures of yesteryear allowed him to acquire knowledge and a critical spirit which distinguished him from his contemporaries. Conversing with Max Roach was often instructive. His entire life was a succession of creative ups and downs which allowed him to have a clear-cut discourse on the cultural contribution of jazz.

Not content with rubbing shoulders with the agitators of 20th century African-American culture, Max Roach was also one of its major players. As early as the 1940s, he participated in the genesis of a musical genre that would revolutionize the musical landscape of the time: bebop. In the 50s and 60s, he invented a form of sound activism intended to shake up mentalities. One of his most vehement attacks against racism and for real social equality was an album, published in 1961, entitled “We Insist, Freedom, Now Suite”. This record called for citizen action while the abuses of white authorities continued to constrain the daily lives of the black community. Beyond the American situation, this major work also evoked oppression on other continents and, in particular, Africa, the victim of centuries-old colonization. The singer Abbey Lincoln, wife of Max Roach, an early activist, obviously participated in this ambitious project by letting her poetic verve burst forth in her rebellious and rebellious voice.

Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Charles Mingus, Nina Simone, and so many others, screamed their anger in the face of injustice, bullying and humiliation. Max Roach never disputed the fact that his art was political and was part of the evolution of morals and societies through the ages. For him, rap was the tasty fruit of his own commitment initiated decades earlier. “In American public schools, music teaching was neglected for a long time. Consequently, all these kids from the ghettos had no other way to entertain themselves than to listen to records. This is how scratching was born. Unable to play on instruments, they learned to play with records. They created a particular rhythm on which they invented poetry that was their own and which described their daily life, their neighborhood, their neighborhood. The impact of words within the black community today is enormous. The violence, the harshness of the remarks, reflect the rage of a generation left to its own devices which did not have the chance to study the arts, poetry, literature, and built itself alone by inventing a language , a culture. These young people were excluded from political life but art is malleable enough to include all the social nuances in its history. Thus, rappers have succeeded in making the whole world hear the plight of the African-American community. Who would have been worried about the situation of black people in the United States if rap had not conveyed this message on a global scale? We discovered a world of violence where drugs wreak havoc, including among the youngest. Today’s artists denounce these situations and appeal for help, to their elders, to their peers, to their governments. It is always amazing to witness this artistic process which pushes human nature to solve its own problems.” (Max Roach on Joe Farmer’s microphone)

Max Roach was an intelligent man. He knew that the key to artistic development was novelty. He had to stay in touch with the times and not get locked in his memories. He had observed the gradual change of his friend Miles Davis towards a modern tone in phase with the renewal of generations. Like his elders and contemporaries, Max Roach has never stopped innovating, constantly questioning himself, without ever compromising or losing sight of the original source of his rhythmic creativity: Africa. As such, he has inspired numerous musicians on both sides of the Atlantic. The late South African flautist and saxophonist, Zim Ngqawana, had the greatest respect for Max Roach and praised his attachment to ancestral roots. “Everyone who buys Max Roach’s records should have in mind that this music has an impact on their lives. If this sound vibration can heal their wounds, it can also instill emotions, be a light in the darkness. If, after a day of work, I listen to Max Roach to relax, and the next day I am once again a slave to society, all this makes no sense. You have to use what energizes you to free your mind. Music is not just a hobby, nor a fun pastime. Max Roach understood this by leading a percussion ensemble called “M’boom”. It’s obviously the sound of drums. On the African continent, we call the vibrations of percussion: “Ingoma”. How do you want to make music without this sound call, without “Ingoma”? Words are often less expressive than the sound itself. Max Roach has proven this to us many times.” (Zim Ngqawana on RFI – March 2006)

Although he was a disciple of Max Roach, Zim Ngqawana wanted to have a fair look at the one he admired and respected. For him, the emotion created by the irresistible rhythm of Max Roach on the drums had to provoke an action, a desire, a desire to provoke events. In other words, music could decide our lives. In his eyes, this spiritual approach to jazz necessarily required perfect artistic mastery. It turns out that Max Roach had instilled this requirement into the playing of many instrumentalists. He himself was an insatiable drummer who was never satisfied with approximation. “The world of sound is, for me, a world in which I am totally invested. Miles Davis, Count Basie, Benny Goodman, were all great virtuosos and, moreover, had an acute knowledge of musical theory and the laws that govern the practice of an instrument. What we gave the illusion of playing in the moment was the result of a frantic search for pure harmony. This technicality eventually became second nature.” (Max Roach on Joe Farmer’s microphone)

Max Roach was born on January 10, 1924 in Newland, North Carolina. 100 years after his birth, his percussive integrity remains an example for many of his heirs.