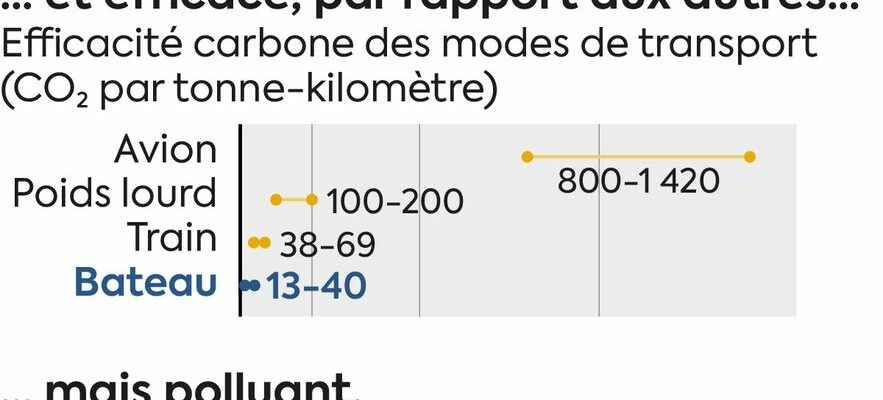

There are nearly 100,000 of them constantly criss-crossing our oceans, carrying huge quantities of goods on board. These bulk carriers, tankers or giant container ships, chartered by Maersk, CMA-CGM, MSC or Hapag-Lloyd, represent the majority of CO2 emissions from maritime transport. Blame it on the heavy fuel oil used in their engines. Aware of the problem, and driven by increasingly restrictive regulations, shipowners are increasingly turning to green fuels. Unfortunately, their production remains desperately low compared to the needs.

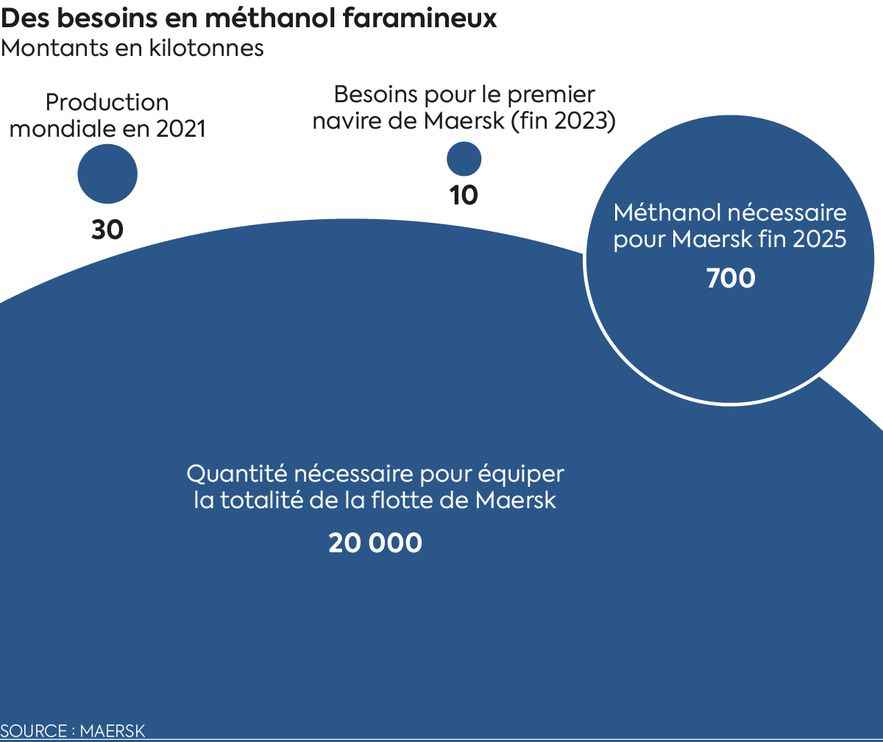

In the plush offices of Danish Shipping, an organization bringing together the main players in the Danish industry, Berit Hinnemann, head of green supply strategy and business development at Maersk, summarizes the situation: “Currently, the global production of methanol – cleaner fuel on which our group relies heavily – barely reaches 30,000 tonnes per year. However, by 2025, we would need 700,000 tonnes to ensure the operation of the 12 compatible vessels in our fleet. That is a 23-fold increase quantities available. And in the longer term, if we were to use this fuel to propel all of our ships, we would need 20 million tonnes per year. That is a 666-fold increase in current capacities.”

What seriously wonder about the possibilities of decarbonization of the sector. Because this challenge of moving to an industrial scale for the production of green fuel concerns all shipowners. Admittedly, projects are springing up everywhere. For example, the French CMA-CGM has joined forces with the gas supplier Engie to produce 200,000 tonnes of biomethane by 2028 using biomass from the wood and waste sectors thanks to a production unit planned in Le Havre. For its part, Maersk sets its sights on Spain. By 2030, two sites, one in Andalusia, the other in Galicia, will produce green methanol on a very large scale. The goal? Supply 10% of the shipowner’s fleet.

A difficult equation to solve for maritime transport.

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

An impossible ecological transition?

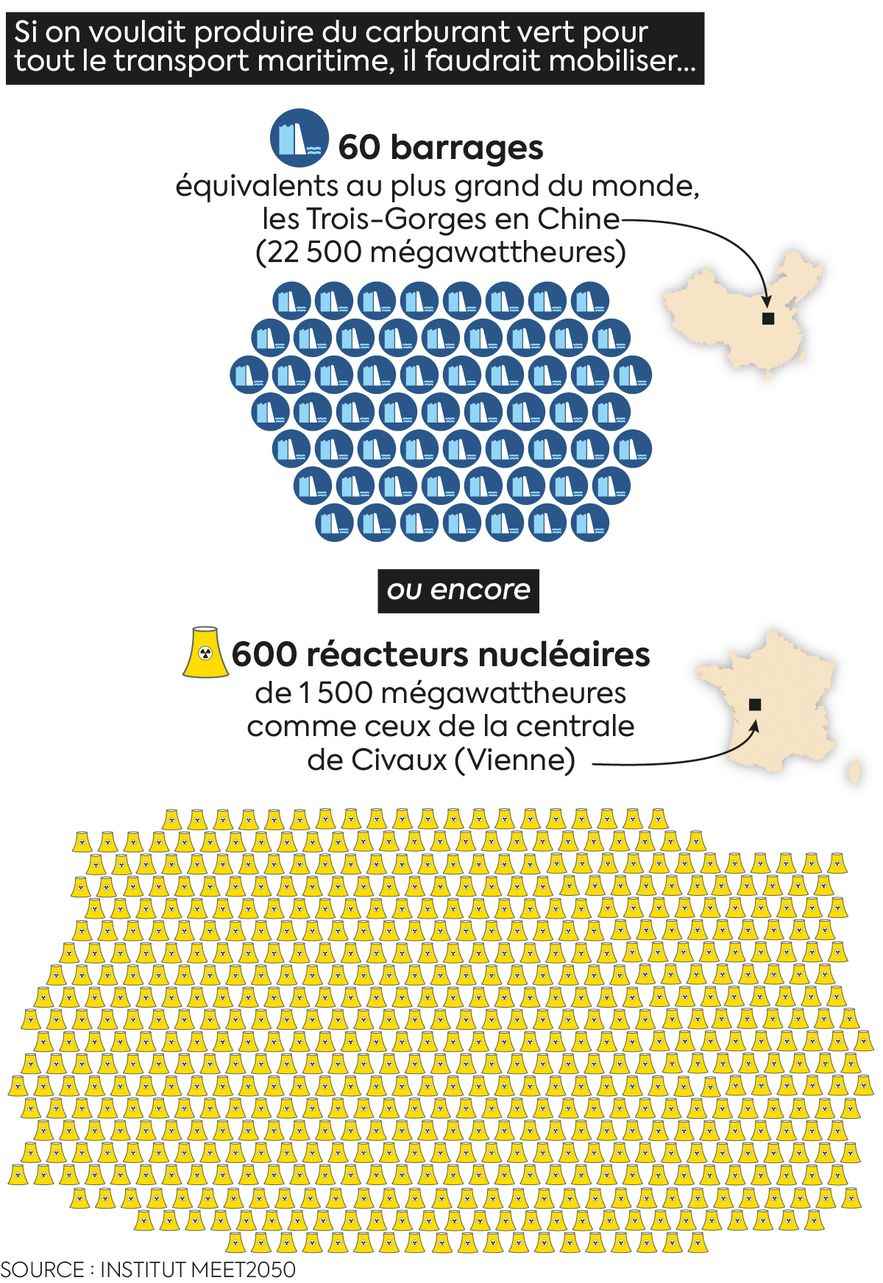

But these announcements leave skeptical Erwan Jacquin, expert in maritime energy transition and former director of research and innovation of the CMA-CGM group: “We will undoubtedly have enormous difficulties in supplying the maritime sector with green fuels. Because it must not be forgotten: the production of these requires a lot of electrical energy upstream.” The expert has done his calculations: today, to operate, large cargo ships consume the equivalent of 3,000 terawatt hours worldwide. If we were to switch to cleaner fuels, be it e-methanol, e-methane or hydrogen, we would probably need double that, or 6,000 terawatt hours. However, this figure represents the equivalent of 60 dams such as the Three Gorges in China – the largest in the world, having displaced millions of people. It is also the equivalent of 600 nuclear reactors like that of Civaux, in France. “Basically, we would have to mobilize 1.5 times the current world nuclear fleet, 1,200 mega solar fields or 4,000 wind farms like that of Saint-Nazaire, just to manufacture fuels for the maritime sector”, explains Erwan. Jacquin.

Is the sector therefore doomed to miss its ecological transition? “We have to overcome the chicken and the egg problem”, recognizes Berit Hinnemann. On the one hand, the producers of ecological fuels do not invest enough because they are not sure of having enough demand for their products. On the other hand, shipowners are struggling to renew their fleet due to the lack of available green solutions: “In truth, they don’t know which fuel to choose for the future, summarizes Erwan Jacquin. Each option has drawbacks, whether in terms of space occupied on board, change or adaptation of tanks and engines, production capacity and supply to ports, not to mention elements related to the safety of sailors and production costs”.

One thing is certain: LNG, increasingly used for maritime transport, remains a transitional solution. It will not make it possible to achieve the objective of reducing ship emissions by 50% by 2050 set by the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

The maritime transport sector condemned to miss its ecological transition?

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

Ten years ago, however, the idea defended by CMA-CGM to use natural gas in its boats for main propulsion, while this solution was traditionally reserved for LNG carriers, seemed disruptive. This path has also been followed by other shipowners since more than half of new boats in the world are now compatible with this fuel, which will not only reduce CO2 emissions compared to heavy fuel oils but also eliminate harmful gases (NOx, SOx) from the atmosphere. But we must now go further. And for shipowners, this means getting their hands dirty, because new fuel-compatible boats not only cost more to build (at least 15-20%), but the entire supply chain also needs to be reviewed. For example, there is no methanol gas pipeline or dedicated port terminal. To use biomethane on ships, it must first be liquefied. However, the units capable of carrying out this work are located too far from the bunkering sites. Others will therefore be necessary.

Huge inertia

“We are talking about several billion euros of investment, recalls Erwan Jacquin. No industrialist can bear this financial burden alone. Unfortunately, the maritime sector has not benefited to date from a major support plan from the State, and it does not have much time left to ensure the success of its ecological transition. CMA-CGM has taken eight years to transpose its LNG technology from LNG carriers to container ships. The inertia is enormous. We must not believe that in five years we will have liquid hydrogen on ships.” In addition, a ship lasts between twenty and twenty-five years. The renewal of the fleet is therefore done in small steps. From 2025, boats compatible with clean fuels should be launched. But these will only arrive in dribs and drabs. In fact, this year, 80% of the world fleet will not comply with the regulations put in place by the IMO. Because although decried, this organization bringing together 174 countries has just enacted new rules.

Huge methanol needs for the maritime sector.

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

For each boat, a new energy efficiency index will be calculated. It will result in a note in the form of a letter. The system is reminiscent of the one already used for household appliances: all ships must be at least in class C. In the event of poor performance, shipowners have three years to bring their ships into compliance, otherwise they will lose their navigation. “It will hit hard from this year, confides an in-house shipowner. Since green fuels are still missing, we will have to use other levers: electrification, CO2 capture on board ships, sail propulsion, improvement of the hull, even if the potential of these measures seems limited.”

Erwan Jacquin goes further: “We need technological breakthroughs in the next five or ten years. Otherwise, the main adjustment variable risks being the speed of the boats.” On paper, this makes it possible to reduce fuel consumption and therefore to more easily meet environmental objectives. However, its economic impact remains largely underestimated. Today, Europe imports 85% of the materials it needs by sea: food, industrial raw materials… “We completely forget it because we don’t see them. But everything goes by boat”, warns Erwan Jacquin. The expert is now campaigning for the implementation of a decarbonization plan for the sector and the creation of a dedicated research center. What create a new wave for the ecological transition.