Nearly half a century after her death, she is still the most famous singer. This December 2, Maria Callas would have been 100 years old. The Greek opera singer turned the opera upside down with her interpretations. Nicknamed the “bible of opera” by the composer Leonard Bernstein, Callas left his mark through his art, bringing sometimes forgotten classics up to date, but also his tormented public life. Of her career, meteoric and interrupted by her love affair with the shipowner Aristotle Onassis, ultimately only a few video recordings remain. This December 2 and 3, one of his most legendary recitals, Paris 1958, is released in theaters (in the Pathé and Gaumont cinemas). At the time broadcast live throughout Europe in Eurovision, the recording is released restored and in color. Interview with Tom Volf, director of “Callas-Paris 1958”, president of the Maria Callas Endowment Fund.

L’Express: Nearly 50 years after her death, why is Maria Callas still so fascinating?

Tom Volf: She is a unique artist. There are no two like her: she has an exceptional career, with an abundant artistic recording heritage. She left this legacy behind her, which means that she is still very much alive, that many people continue to love her, to be interested in her. And it’s not just the career: there is also life, which is a special life, particularly short, since she died young, at 53, in the spotlight.

She made opera so exciting, exciting and accessible to everyone, that she very quickly went beyond the world of opera and acquired a notoriety that she maintains. This not only concerns lovers of lyrical singing, but also people who don’t really listen and on whom it exerts a sort of fascination. Callas is a wonderful gateway to the world of opera. It was for me: I discovered it when I was 28, ten years ago now, when I knew nothing about the subject before.

How is she unique among singers?

It’s linked to his way of being. Maria Callas was not just a singer: she was also a tragedian. She was an actress who embodied her roles, who resurrected operas that had fallen completely into oblivion, like Norma – which she made a standard. She made a big impact through her different interpretations and her roles. She has an absolutely dazzling and global career. She has changed all over the world, whether in opera houses or in concerts, since she has done absolutely gigantic tours, comparable to the tours that singing stars do today. She is particularly at this level in this year 1958 when she is at the peak of her career, she gives more than 50 concerts around the world with performances in London, New York, Dallas, and then, at the end of the year, in December, in Paris.

Why did you choose this particular recital?

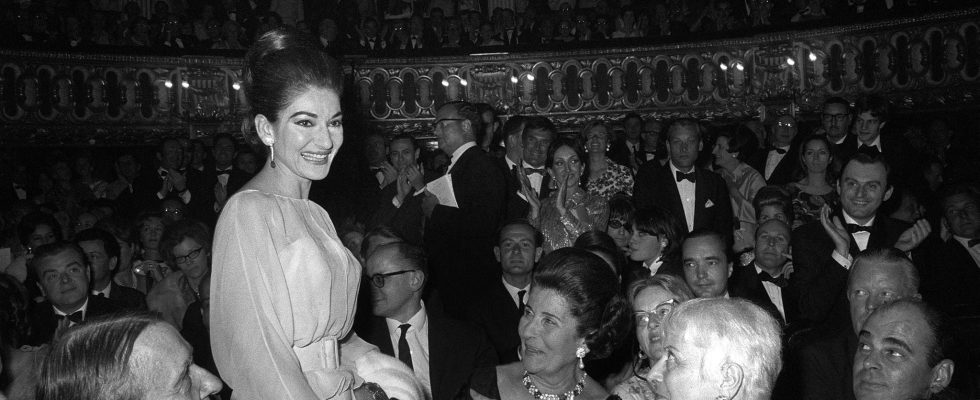

There is very little film footage of Callas. The Paris recital in ’58 was broadcast on live television, but only a poor quality black and white copy remained, and it was already a document that was considered invaluable for decades. It turns out that two years ago, as part of the mission of the Marias Callas endowment fund, we received help from several of her relatives, donations of archives that she had kept at their home, spools of thread, and in particular the original spools of this famous representation. We have undertaken restoration work entirely in color, with the original sound, which allows us to bring this evening at the cinema back to life. It is a way of bringing back to the spectators of 2023 the experience closest to those, lucky ones, who were present at the Paris Opera in 1958. The cinema is one of the only places which allows, today, to see Callas as if she were in front of us, in immersive sound comparable to opera.

In 1958, she was at the top of her art. She is in exceptional vocal form, which will only decline thereafter. She performs this evening in Paris in a format that she has never done before and that she will never do again. It is neither a recital nor an opera, but both: it is an evening in two parts. First a recital with three of her greatest arias, including Norma, obviously, which she chooses to perform verbatim, as well as two other opera arias from her favorite repertoire which is the belcanto. In the second part, the second act of Tosca, entirely staged and in costume. Not only do we have Callas at the top of her art, but we also see her in all her artistic aspects: both the singer and the tragedian. In Tosca, she plays an absolutely dramatic character, in an extremely lively way. In his time, people were fascinated to the point of queuing day and night for tickets to his performances. The charm still works a little today.

How can we explain the fact that we have so few archives of Maria Callas’ performances?

We’re talking about a time when, quite simply, the simplicity of recording wasn’t what we have today. No one imagined, moreover, that his career and his life would be so short. There was no particular approach to preserve his work. Even the evening of ’58 was not supposed to be recorded: although broadcast live throughout Europe – in Eurovision, which was the peak of technology at the time – it was not intended to be preserved. If Callas had not asked to keep a 16mm recording for his personal archives, we would no longer have any trace of this evening. It’s a miracle to have it today.

Other singers were able to sing until very late in life, with careers spanning sometimes 40 years. Not the Callas. Her career was particularly short because, on the one hand, she kind of burned her life out at both ends. The year 58 is very representative of this. The amount of performances and recordings she accumulated meant that she lived like a top athlete. To extend the metaphor, we can say that she ran the Olympic Games every year. Her meeting in 59 with Onassis meant that she moved away from the scene a little, then returned to it. But she will never be at the level she was at until then. She began a vocal decline in the 1960s. Her operatic career ended in 65, and her stage career less than ten years later.

Her love affair with Onassis, which began in 59, amplified her fame. Onassis was already known: he made headlines at the end of the 1950s. Their tumultuous love story – married, they will divorce for each other – will only strengthen their notoriety. Subsequently, the arrival of Jackie Kennedy in their lives – Onassis will leave Callas to marry the latter – will strengthen the soap opera. Callas aspired to the love life of a simple woman, but the elements will have decided otherwise.

She has also become a fashion icon.

To meet its own requirements, not to feed its notoriety! She was fascinated by fashion, by the Milanese high society she encountered in the early 1950s. She wanted to resemble the people and celebrities she admired, like Audrey Hepburn. This is how she shaped the look we know her over the years. This was more a desire to shape one’s own image than a desire to change it for the public. When asked why she lost weight, she replied that she did it because she wanted to play Medea. She felt too heavy for the character and felt the need to have more defined features. The demands she had for herself and her characters shaped that.

Which song would you recommend starting with to discover Maria Callas?

This Paris 58 recital is truly complete. There’s everything in it: Norma, her full-fledged role, the trouvère, Trovatore, which is one of her great dramatic roles, the Barber of Seville which is in a completely different, lighter register. And finally, the second act of Tosca, which constitutes the whole drama, the theater, this operatic side that we imagine. It is an overview of the quintessence of his repertoire. Not much is missing. To this, we could add the other great roles that she scored: Traviata, Medea, Bellini, Donizetti, Rossini and finally Verdi, whom she loved more than any other.