We won’t regret 2022 much. Full of sound and fury, this year will undoubtedly be remembered as the year that took us one step closer to global chaos. Private (or sporting!) pleasures cannot extinguish the anxiety caused by a world and a France in the throes of increasing entropy.

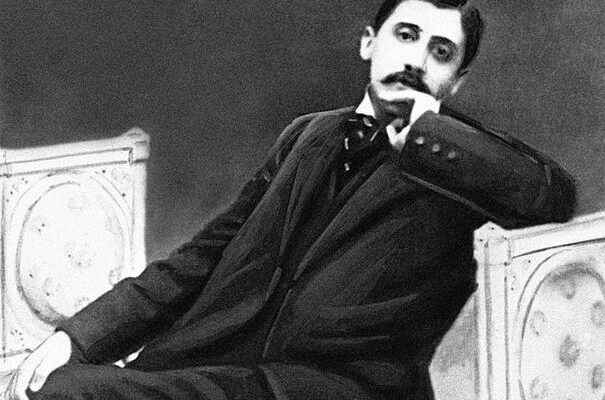

A small twinge in the heart however surprises us: it is that with 2022 the Proust year ends. Throughout the year, we will have tasted the particular flavor of this permanent counterpoint to our ordinary follies. Proust on booksellers’ stalls, Proust in magazines, Proust read, reread, exhibited, studied, discussed: we thought we were seeing the vanished world of Marcel Proust reappear constantly, like the basso continuo of heavy news.

Certainly, in the real success of this year Proust, there were complacency. There is no doubt that part of Proust’s posthumous success was due less to his literary genius than to nostalgia for a world where social order and the art of living went hand in hand. We have seen the appearance of books on Proust’s objects, Proust’s favorite places, Proust’s cooking recipes summoning the rather French regret of an ancestral province and a bourgeoisie sure of its customs. The furniture smelling of polish, the regularity of the uses, the refinement of the manners make the heartaches of this confined world seem almost benign. The presence of Proust in our national imagination is perhaps not totally different from that of Downton Abbey in the British imagination.

beacon in the night

Something other than these surface impressions gives Proust a singular place in our national Pantheon (which, despite the efforts of Charles Dantzig, the writer will not have entered). Let’s see: where was the world a hundred years ago when Proust died on November 18, 1922? The deadliest of world conflicts had been succeeded by the Spanish flu pandemic and its tens of thousands of deaths. Already, in Italy, fascism is marching on Rome, and the NSDAP was founded by Hitler two years earlier. While everything was unraveling, Proust was writing. However, to the grimace of the world, he did not oppose the pale rage of Annie Ernaux (Nobel Prize for Literature 2022), nor the rawness of a Virginie Despentes (more than 200,000 copies sold of Dear asshole), both so certain of ultimately appealing to a readership mainstream, but the voluntary marginality of his existence – and, which is the writer’s greatest bet, the invention of a language that was his only. He stood apart. He excepted himself. Knowing nothing of the dark paths down which humanity was heading, he held out to it from the depths of his solitude a mirror of unheard-of purity. Memory was for him that viaticum through which he was able to recapture the substance of our common experience.

That Proust was celebrated when, following a global pandemic, war returned to Europe, and with it shortages, social tensions and the anguish of a new step towards decline, offered a disturbing perspective on the history of our continent: one hundred years later, where is our Proust? Where is this French writer who would tear his work from the darkness of time to build a literary ambition far exceeding the contingency of the moment? Where is this writer who would know how to ward off the procession of miseries with which History is fertile in order to rediscover the invigorating source of human experience, and tell us again of its juice? Where is this writer who, without blinding himself to the horror of war, would also know how to hear the beauty of the world and restore its intimate pulse?

Rereading Proust in 2022 was certainly, in the cold light of events, questioning the powers of literature, but also the faith in humanity that a work like The research. Worldwide, The research is read in various translations because it is not the testimony of a certain French spirit, but because it is a beacon in the night for who still knows that humanity is not a horde delivered to its passions , but the delicate and infinitely fragile assembly of the sweetness of memory and sorrow, of secret loves and the intermittences of the heart, of the pains of each day and the hopes which dissipate them. Proust did not practice silly optimism; he was however persuaded that humanity could still be saved from itself, and first of all by literature. Let’s propose that 2023 is also a Proust year.