The weight of the symbol. In Lützerath, a small hamlet in North Rhine-Westphalia wedged between Aix-la-Chapelle and Düsseldorf, there was an air of strange defeat for the Energiewende this weekend, Germany’s energy transition strategy. Soon swallowed up by the extension of the local mine, and its giant excavator, this village occupied for several weeks by the militants of a ZAD welcomed several thousand demonstrators of the ecological cause, who came to protest against the exclusion and the destruction of this hamlet, and more generally against the strong comeback of coal in the country and its disastrous effects on the climate.

In front of them, the police came in large numbers. Under their boot, the wet ground quickly became soft, so much so that some ended up mired. Images that have toured Europe, symbol of a failed German transition. The Express explains why.

In 20 years renewables have accelerated without eliminating coal

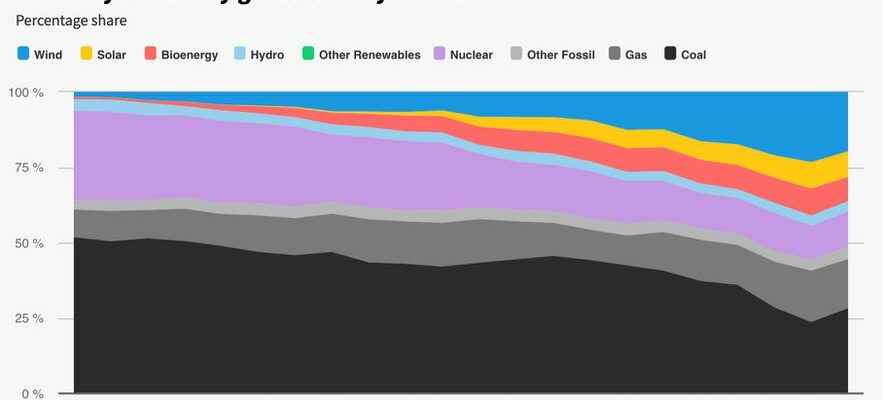

This is undoubtedly one of the great successes of the German model. In the space of 20 years, and thanks in particular to a massive policy of federal subsidies and aid – more than 500 billion euros, Berlin has succeeded in massively increasing the weight of renewable energies in the electricity mix. Solar and wind energy, which represented 0.01% and 1.63% of the mix respectively in the early 2000s, have increased to 8.47% and 19.69% in 2021 according to data from the specialized think tank Ember.

Including bioenergy and hydroelectricity, almost 40% of German electricity production is now of the renewable type, compared to barely 5% at the start of the century. An effort to be commended and which has actually contributed to the reduction in the weight of coal in the country, which represented, it must be remembered, more than 51% of the electricity mix in 2000.

The fact remains that by closing a large part of its – carbon-free – nuclear fleet, following the decision of the federal government in 2011 and the Japanese disaster of Fukushima, Germany shot itself in the foot on its climate trajectory. . Indeed, to maintain a base of controllable power plants and thus cope with the intermittency of solar and wind energy, Berlin had no choice but to massively import (Russian) gas and develop many thermal power plants operating with , but also to maintain a considerable fleet of coal-fired power stations. The latter still represented 28% of the electricity mix in 2021.

German electricity production by energy

© / Ember

Holes in the wind development racket

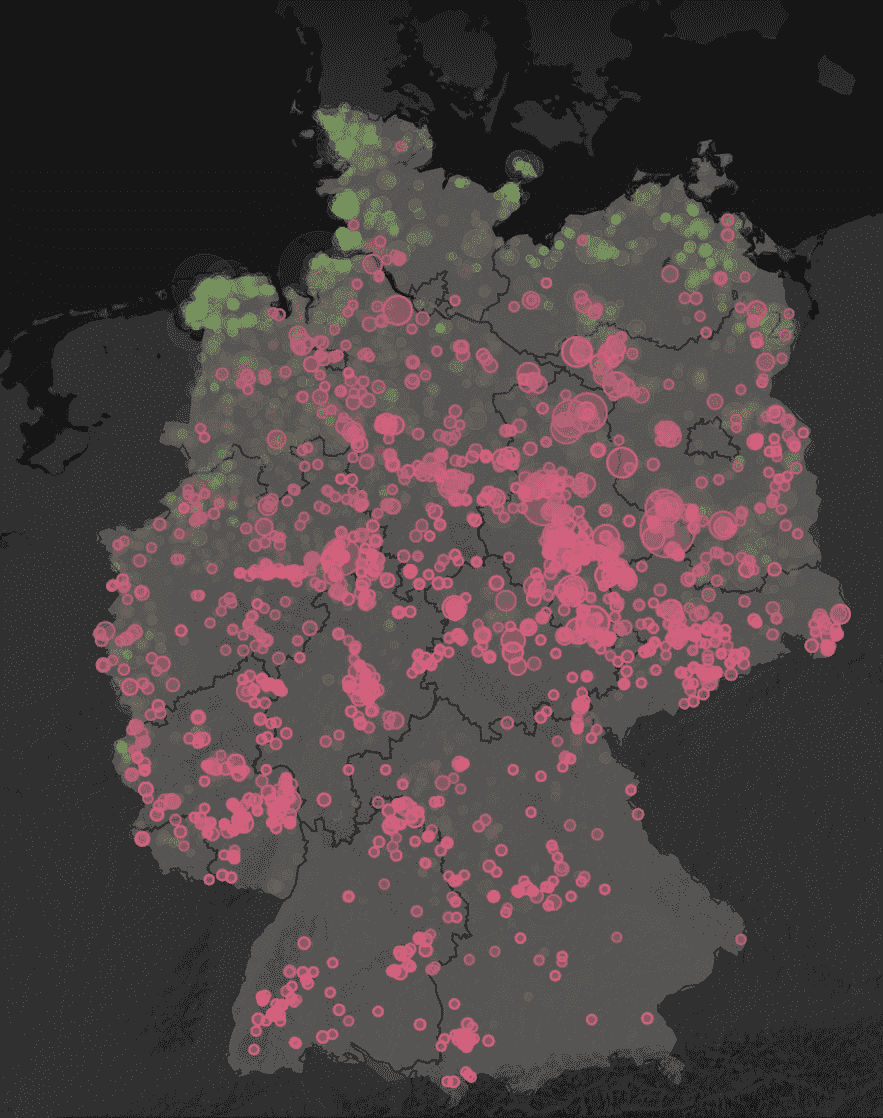

If the rise of wind energy on the other side of the Rhine has been extremely rapid, while it is largely slipping in France under the weight of local opposition and the stiffness of the administrative apparatus, several media surveys locals have recently demonstrated the sometimes anarchic character of development. In a long survey published in early November, the Neue Züricher Zeitung was able to estimate thanks to the detailed analysis of meteorological data over 10 years concerning 18,000 wind turbines out of the 28,000 in the country, that a quarter of them were operating with a load factor of less than 20%.

This ratio between the energy produced and that which could have been if the devices were operating at full power is puzzling, recently reminded the Express: it is less than 10% in 25% of cases! Still according to this work, only 15% of the wind turbines analyzed have a load factor exceeding 30%. The vast majority of these are infrastructures located in the north of the country, where the wind conditions are the best.

In the south of the country, on the other hand, wind turbines have to deal with more unfavorable weather conditions while electricity needs are higher in this area, noted the media. As a result, construction sites to create high voltage lines and transport this electricity from north to south are multiplying, regularly provoking local opposition. the Neue Züricher Zeitung also recalled in his study that without subsidies, many of these wind farms were in deficit and could not operate. While the federal government is trying to accelerate the establishment in the south, producers are for many relatively reluctant. Of course, this analysis does not call into question the merits of wind energy, even if the low yields observed have probably prompted the production of fossil energy to compensate. The map below highlights above all the importance of geographical location.

A quarter of German wind turbines have a load factor of 20%.

© / NZZ

A higher carbon intensity of electricity than its neighbors

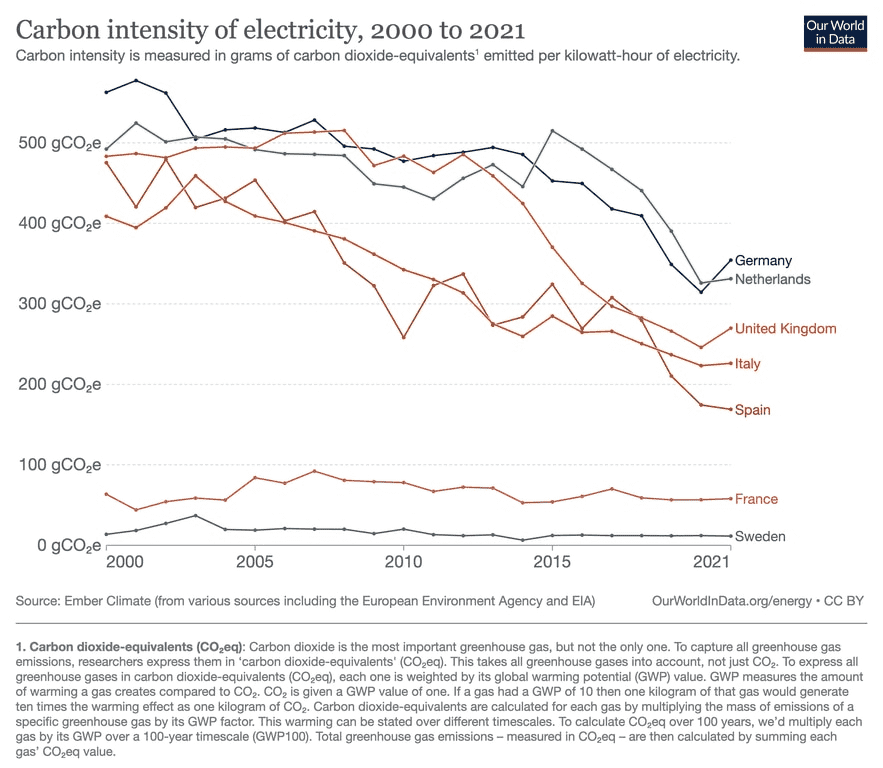

Naturally, maintaining an electricity mix still largely fueled by fossil fuels (48.48% in 2021, according to Ember) including a substantial share of coal – by far the most polluting energy in terms of CO2 emissions – , results in a very high carbon intensity of electricity production and thus higher than its neighbors.

As the graph below illustrates, the massive development of renewable energies in the country has had a real effect on the carbon intensity of electricity production between 2000 and 2021. Despite this, this figure remains very far from Sweden or from France, the two best European students in this field. At 354gCO2/kWh in 2021, German electricity was six times more emissive than its French neighbour, which can count on nuclear power, and not far from 30 times more emissive than Sweden, whose mix includes nearly 30% nuclear power and a large hydraulic capacity.

The comparison of Germany with the United Kingdom is even more interesting. In 2012, the two countries emitted almost the same amount of CO2 per kilowatt hour of electricity. A little less than ten years later, London is posting much better results than Berlin, with a figure of 270gCO2/kWh for the same rate of renewable energies in the mix (around 40%). If part of the difference can be explained by deindustrialisation and the fall in electricity consumption in the United Kingdom, the maintenance on the other side of the Channel of a large fleet of nuclear reactors associated with a push for renewables similar to Germany has made it possible to decarbonise the electricity mix and therefore part of the economy much more effectively.

It should also be noted that the carbon intensity of German electricity even increased in 2022 and for the second consecutive year, to 380gCO2/kWh according to data from the European electricity network operator Entsoe. A rise no doubt cyclical, linked to the German decision to completely dispense with Russian gas. While waiting to be able to remedy this situation of ultra-dependence via the development of new partnerships for the import of gas and the acceleration in renewables, Berlin is obliged to resort more to coal. With the deleterious consequences for the climate that we know.

A much more emitting electricity production.

© / OurWorldInData

Insufficient contribution from other sectors

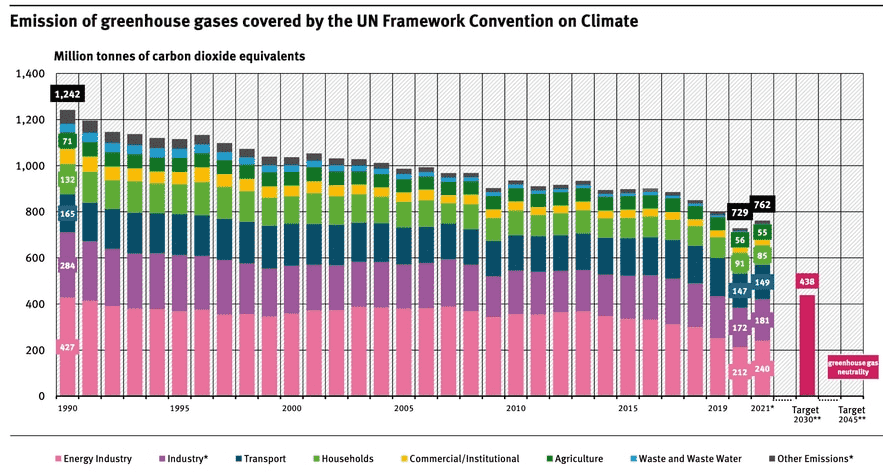

Obviously, electricity production is a major point of the German energy transition strategy. Like the events of the past weekend, this crystallizes a lot of tension on the spot. It is also a sensitive point on this side of the Rhine, because of the choice made by our German neighbors to do without nuclear power and it must be said of Berlin’s maneuvers to fight nuclear power, particularly in Brussels. But in terms of decarbonization, transport, construction and industry are also sectors to watch closely. Every year, the German Federal Environmental Protection Agency carries out a sector-by-sector balance sheet in terms of CO2 emissions.

Insufficient contribution from other sectors.

© / German Federal Agency for Environmental Protection

Looking at the figures, we can note that in industry, transport or even housing, CO2 emissions have been falling in absolute value since the beginning of the 2000s and the start of the major German energy transition plan. Still, this reduction is insufficient. In detail, in fact, industry has shown a rate of reduction of only 0.52% of its emissions per year since 2000, against 1% for transport, and 1.63% for the housing sector. As the German Federal Environmental Protection Agency pointed out last March, “without massive and rapid additional efforts”, the objectives of reducing emissions by 65% compared to the 1990 target and carbon neutrality by to 2045 cannot be achieved.

Overall, an energy transition with mixed results

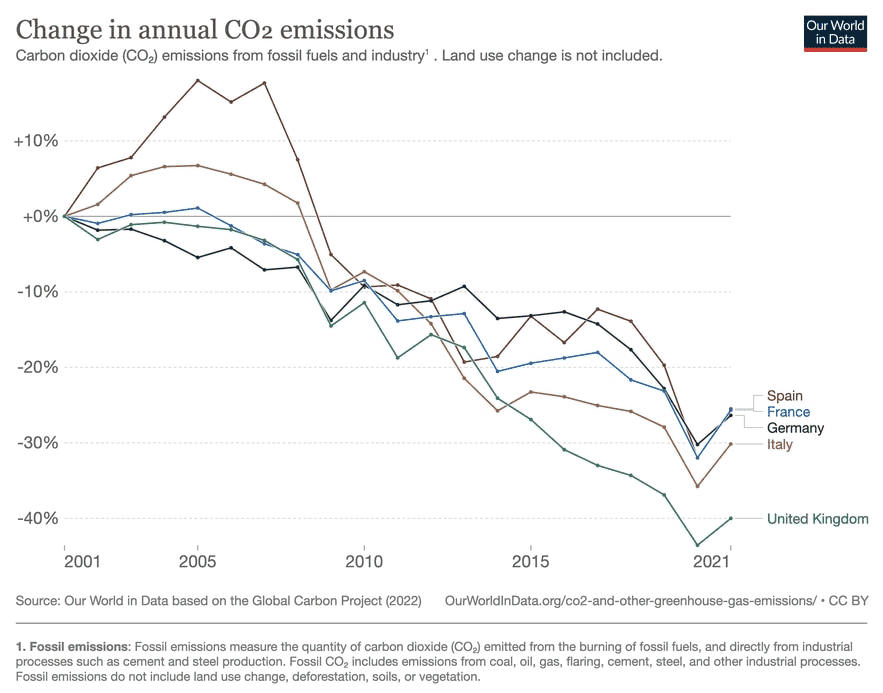

Since 2001 and its official launch, the Energiewende has not been a failure strictly speaking. According to the data in the graph below, Germany has reduced its CO2 emissions by 25% since the turn of the century. A rate that places the German country in the same wake as France or Spain. Faced with the urgency of the climate crisis and the urgent need to decarbonize a country where coal still kills more than 20,000 people prematurely each year, the choice to turn away from nuclear power has not finished being interrogates.

The German energy transition, a mixed record.

© / OurWorldInData

The example of the United Kingdom, which succeeded in reducing its emissions by 40% over the same period and virtually eliminating coal from its energy mix, is eloquent in this regard. The future, too, is dotted. The German decision to do without Russian gas, for obvious geopolitical reasons, risks for a few more months to be compensated by an additional use of coal. The coalition of Social Democratic Chancellor Olaf Scholz thus recently authorized 27 coal-fired power stations to resume production for a limited period until March 2024. And the millions of tonnes of CO2 that go with it.