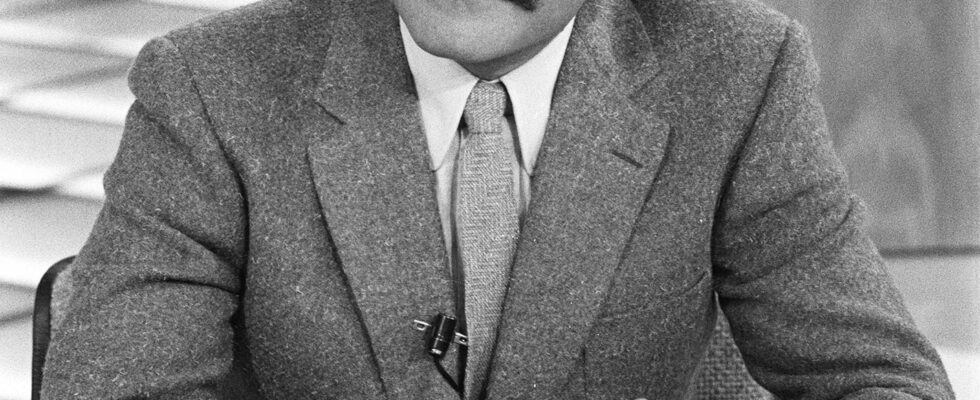

It is 1969, in the offices of the BBDO agency, on the Champs-Elysées. A young Rastignac of 20 years old, just arrived from Issoire, Thierry Ardisson, serves as factotum. The creative director, Yves Navarre, 29 years old and not yet a writer, spotted him. Rimbaud and Verlaine atmosphere among pubards. Thanks to Navarre, Ardisson is gaining ground. Then Navarre, who was giving dinners in honor of his foal, understands that he will not be able to put him in his bed – their paths separate. Twenty years later, in 1989, having become a TV star, Ardisson invited his former mentor to the set of Black glasses for sleepless nights. Winner of the Goncourt Prize in 1980 for The Acclimatization Garden, Navarre is already old-fashioned – he committed suicide five years later by choking on a plastic bag after swallowing medicine. On the Ardisson set, the melancholic and mustachioed novelist responds to an “anti-Chinese portrait” interview. What would he be if he were poison? “Literary criticism,” he laughs. While the Séguier editions publish its Newspaper unpublished (preceded by a fascinating biography by Frédéric Andrau), let’s try to rewind Navarre’s life without adding cyanide.

He at least will not be able to invent the trajectory of a class defector: born in 1940, Yves Navarre grew up in a house in Neuilly-sur-Seine. Every Sunday, he plays golf with his father, who also takes him to the Comédie Française. The first frictions occur during adolescence. Mr. Navarre understands that his son prefers boys. He thought for a while about having him lobotomized, before narrowly changing his mind. In 1964, leaving EDHEC, Yves Navarre had to do his military service. We send it in cooperation to Senegal. He sings in a nightclub in Dakar, Le Pigalle. That’s not enough to make the pill pass: he quickly returns to France, is interned in a psychiatric ward in Val-de-Grâce where he is declared insane (because of his homosexuality) and obtains reform.

To earn a living, he started in advertising, at Havas, Publicis then BBDO. He loves art, he has an eye, and buys paintings by Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and David Hockney – Hockney will also paint the portrait of Navarre, which can be found on the cover of the pocket edition of Turkish delight. In 1969, he went to New York. He hangs out in fishnet stockings in backrooms and roams other gay cruising spots (saunas, docks, parking lots). On his return, he sold his paintings to acquire a house in Joucas – a small village in the Luberon where his neighbor was Raymond Aron. There, the graphomaniac writes, with the anxiety of being a failure: his first 17 manuscripts were rejected by all the publishers.

From Goncourt to the nuns

At the 18th text, bingo! Paul Otchakovsky-Laurens (the future POL) offered him a contract with Flammarion. Lady Black appeared in 1971. Jean-Louis Bory hails a “Jean-Jacques Rousseau of the post-Freudian era” but, in The literary Figaro, a certain Bernard Pivot puts a damper on this enthusiasm, criticizing “the most immodest and most narcissistic novel of the year” – while recognizing certain qualities in it. Regardless, Navarre’s literary career was launched. In 1972, he sympathized with Roland Barthes and Françoise Sagan, two friendships which would remain important to him. In his Newspaper, he writes this about Barthes: “A real encounter. A real tenderness. Something elegant (and lost) in our bourgeoisie unites us.” He calls him a “guide”. For his part, Barthes will say that Navarre is “the last cursed writer” because he is irrecoverable by any intellectual coterie.

Over the years, he has been considered for awards. At Goncourt, he is supported by Michel Tournier (who gives him a cat). One day, he meets another juror, Robert Sabatier, who does not hide from him that he does not open the books. Navarre learns that Patrick Grainville obtained the Goncourt 1976 for The Flamboyants by blackmailing suicide! Is this a good strategy? Reality, unfortunately, sometimes goes beyond comedy. In 1979, his comrade Jean-Louis Bory killed himself by shooting himself in the heart. Nine months later, Navarre reports a new drama in its Newspaper : “I learned this morning that Roland Barthes died. Roland was my only teacher to feel, to feel (feeling, resentment). The upheaval will come later, in the days to come. I miss him. I will miss him.” Winning the Goncourt the following fall was not enough to console Navarre.

The 1980s were paradoxical for this great lunatic. Some critics take pleasure in downing it. When leaving Biographyin 1981, the young Eric Neuhoff shot these “700 pages of moans and recriminations”: “At 40, Navarre has the luxury of signing a doting work.” The one who defines himself as a “socialist faggot” is close to power: he frequents François Mitterrand and especially Jack Lang. In 1986, Pivot invited him to Apostrophes. But our man publishes books at an unreasonable rate that sell less and less. He is becoming visibly bitter. In 1989, after accompanying Mitterrand on an official trip, he had the revelation: Canada would be the Promised Land! He will be disappointed with the trip. Navarre settles in Montreal, haunts sordid saunas, becomes depressed. He repeats over and over in his Newspaper that we must “hold” before noting in 1990: “Why hold on?” On his return to Paris, penniless despite his inheritance, he was welcomed for a time by the Augustinian nuns of Rue de la Santé, who housed him in the dovecote. He then moved to rue Malher, in the Marais, where he ended his life.

Fight against oblivion

Like all writers worthy of the name, Navarre was unclassifiable, irreducible to the right or the left, as Barthes predicted. Is this why his Newspaper, a real editorial event this spring, has gone completely under the radar? The book is nevertheless colorful. We see Navarre chatting with Marguerite Duras, dining with Jacques Chazot, drinking good Bordeaux with Paco Rabanne, literally catching fire at Marlène Jobert’s house, his suit jacket having touched a candle… He has erotic dreams during which he is the lover of POL Upset that a screenplay he wrote for Jean-Claude Brialy was not accepted by the CNC’s advance on receipts commission, he compares the latter to the Gestapo – just that. He has no more tender words for Bernard Frank (“a drunkard”), the duo formed in his eyes by Philippe Sollers and Bernard-Henri Lévy (“clowns”) or the freeloaders who have their napkin ring at the Ministry of Culture (“shit people”).

His homosexual colleagues are his favorite targets: Roger Peyrefitte, Matthieu Galey, Renaud Camus and Angelo Rinaldi thus receive his most vicious arrows. Testifying in the biography which completes the Newspaper Properly speaking, Jack Lang states: “Yves was a wonderful man, often tormented, sometimes bordering on despair, but always a complete friend.” Jacques Brenner is no longer there to bring him the contradiction – he considered Navarre proud above all. With this gossip, let’s separate the man from the work for a second and try to place Navarre’s books in the French literary history of the 20th century: somewhere between those of Jean Genet, Hervé Guibert and Jack-Alain Léger? This means if The Acclimatization Garden and others deserve to escape oblivion.

Newspaper, by Yves Navarre. Preceded by a biography by Frédéric Andrau. Séguier, 505 p., €29.

.