He does not drink alcohol, cigarettes are unknown to him, and yet it is indeed drunkenness that inhabits him in its natural state. At 61, Lassaâd Metoui, a calligrapher from Gabès, Tunisia, who lives in Nantes, never stops dialoguing with ink like a monk entirely turned towards his religion: for him, that of “thought, creation, contemplation”. We could add to this the praise of slowness, which the artist has always cultivated.

After the 2018 retrospective event at the Arab World Institute, The Drunken Brush, Here he is back with Ink drunkenness, this time on his adopted land of Nantes, where Bertrand Guillet, director of the Château des Ducs de Bretagne, gave him carte blanche. As usual, Lassaâd Metoui took the time to build an entirely new project in keeping with the place: a total of six years of work, four of which were devoted to reflection and two to the actual realization. More than 50 unpublished calligraphic works are thus hung on the walls of the former royal fortress, divided into around twenty sections which are as many invitations to travel and meditate.

The magic of the reed

Since his beginnings in Europe in the 1980s, Lassaâd Metoui has embodied the link between a centuries-old tradition and expressive contemporary art. In the oasis of his childhood, between the desert and the sea, he discovered “the magic of the reed capable of generating the splendors of lines, curves and shapes”. While his friends were passionate about football, he devoted himself to calligraphy from the age of 6, a demanding training that he continued as a young adult at the Beaux-Arts in Gabès, Toulouse, Brussels and then at the Ecole du Louvre. His sources of inspiration draw both from Western painting (Matisse, Klee, Soulages) and from Far Eastern art, particularly Japanese. In the background of his exhibitions, he often calls upon a philosopher to guide his research and support his argument. Ink Drunkenness does not deviate from this by echoing the thinking of Kitaro Nishida, the founder of the Kyoto school, who, during the first half of the 20th century, distinguished himself by associating Western metaphysics with Eastern spirituality. Inspired by the concepts of the Japanese master, Lassaâd Metoui wrote down the key words in his notebooks in their original language and drew multiple preparatory sketches before turning them into canvases.

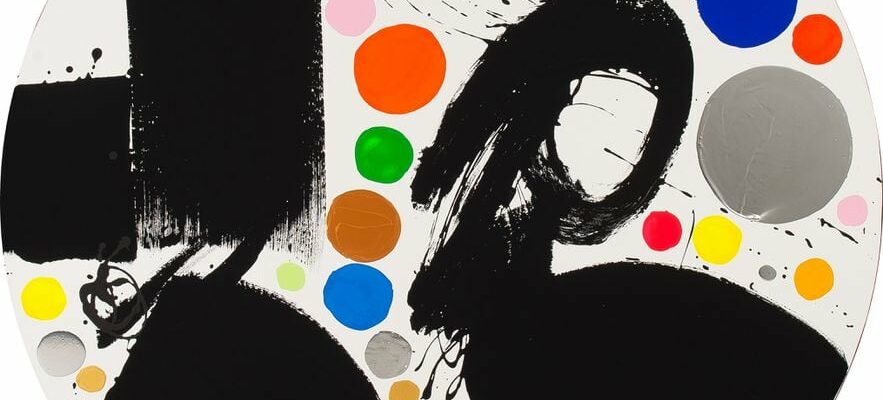

Lassaâd Metoui, “The world of the intelligible 2” (2023).

/ © Lassaâd Metoui © Le Labographique

It is therefore a whole philosophical journey that presides over the Nantes journey, in which the visual artist has introduced three new elements into his corpus: a new black that absorbs light 100%, but also a material offering the same reflection as a mirror, in a nod to the paintings of the Flemish primitive Jan van Eyck, and finally the round format, which calligraphic abstraction very rarely uses. Enough to explore further this relationship between motif and words, drawing and verb. Moreover, like the links that united Matisse and Aragon, Lassaâd Metoui also has “his” writer: David Foenkinosunconditional of the one he calls “the athlete of aesthetics”. The praise of slowness, again, when, according to the author of Happy Life, “At a time when we are suffocating with frenzy, it is so appreciable to consider creation as a space where time takes the time to offer itself to us without artifice.”

.