This June 30 will have signed the death of Macronism as a political movement. Of course, one will respond that President Macron is still in office, and that whatever the result of the second round, he will have a crucial role to play in his last three years of mandate. One could also argue that his parliamentary group, a priori composed of 60 to 90 deputies (a figure to be confirmed on the evening of the second round), could play a key role in the formation of a coalition, whatever it may be. Nevertheless: Macronism has suffered a major setback, and this one should be fatal to it. In a chamber of 577 deputies, what remains of the Macronist parliamentary group will have difficulty making itself heard, and even more so given the unpopularity of the president, which was clearly felt both during the European elections and during the legislative campaign.

What is more, the Macronist “party” is not one: although it has legally existed since 2016, it has never been anything but the electoral conquest vehicle of one man, Emmanuel Macron, and its only victories have literally been his own. This means that the candidates of this party have not recorded any success in local and regional elections, thus preventing En Marche (now Renaissance) from taking root in the French political landscape. Without representation at the local level, without a majority parliamentary group, without the prospect of the distribution of ministerial portfolios (or other honors) by the President of the Republic, it is likely that Emmanuel Macron’s party will disappear as quickly as it appeared, leaving a space that, natural law helping, will quickly be filled – in the meantime, surviving elected officials and former ministers will have to start looking for a new political home in the perspective of the announced renewal of 2027.

The pioneer Meloni

In fact, what is happening to Macronie is what it did to the Socialist Party and the Republicans seven years ago: a confrontation with a radical political paradigm shift, capable of making entire political families disappear. In 2017, the traditional right-left divide was dying, and both Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen had castigated in their own way the “UMPS” system (named after the former name of the Republicans) to replace it with a division between elites and populists, a division that was also found at the same time elsewhere in the West, whether in the United States, the United Kingdom, Hungary, Poland or even Italy, where Matteo Salvini’s Lega had allied itself with the Five Star Movement in a populist coalition in which the only thing that mattered was the desire to overthrow a system perceived as unjust and far removed from the aspirations of the people.

Italy, precisely the one that was a pioneer in populist exploration, experimented with Giorgia Meloni with post-populism, this overcoming of populism whose central element is the return of the right-left divide. The figure of Meloni was central to this transition, she who always identified with the right and refused cooperation with the left (populist or not). With the end of Macronism, we are witnessing the same spectacular return of the right-left divide, defined by this now almost direct confrontation between the New Popular Front – which sometimes has the appearance of a “Republican Front” when its representative comes from Emmanuel Macron’s party or the moderate left – facing the National Rally, which is still struggling to make allies beyond its own ranks.

End of the populist crisis?

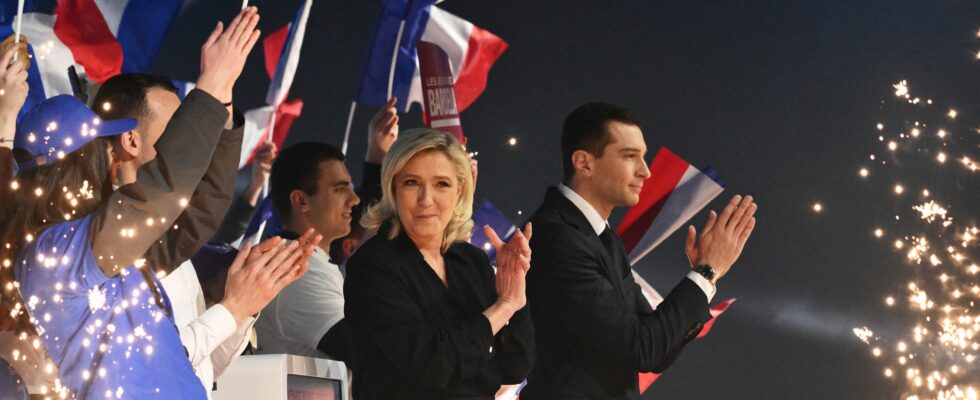

The French left understood this paradigm shift before the others in the aftermath of the European elections, and this explains the rallying of all its sensibilities around this concept of the Popular Front with a 1930s feel – certainly insufficient to obtain an absolute majority (the country’s shift to the right has passed through there), but sufficient to impose itself as one of the two poles of the political spectrum. This does not of course mean that the left is uniform – it is plural, as it has always been since that evening in August 1789 when the reformist deputies aligned themselves to the left of the president of the constituent assembly to vote for a suspensive (and not absolute) veto of the king. Similarly, the right is also plural, and even if it still has difficulty finding its way in the new political situation, Jordan Bardella is trying to clearly position his party as the representative of this right, alone against the extreme left. It is also a safe bet that this new speech will not please Marine Le Pen, who has always refused to position herself on the right “against the UMPS” and largely prefers a duel with Emmanuel Macron, populists against elites. She may not know it yet, but the emergence of Jordan Bardella has made her obsolete on a political chessboard that is increasingly defined on this left-right axis, and less and less on that between populists and elites.

It would be bold to predict the victory of one or the other camp in the second round of these elections – the variables are so numerous, and everything is still possible, including an elusive chamber with a necessarily weak technical government, which would give back a little power to Emmanuel Macron. In the meantime, he will be able to meditate on the return of the left-right divide, which in the long term could perhaps put an end to the populist crisis that we have been experiencing since 2010.

*Thibault Muzergues is a political advisor at the International Republican Institute and the author of Postpopulism (Ed. of the Observatory).

.