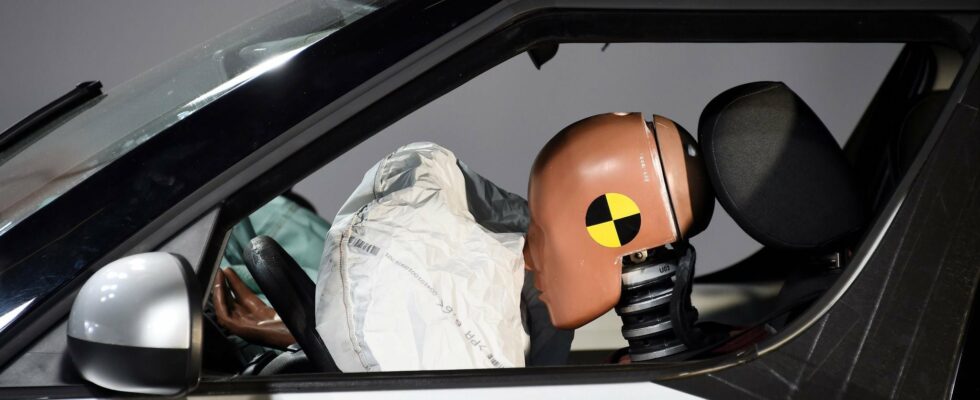

Its defective airbags are the cause of one of the biggest automotive scandals. And were right about its existence. Disappeared with losses and crashes in 2017, the Japanese equipment manufacturer Takata marketed airbags made of ammonium nitrate for years. However, when exposed to humidity and heat for a long time, this cheap chemical component becomes unstable and potentially explosive. Enough to transform equipment intended to protect drivers into real time bombs. A disastrous choice which gave rise to the largest recall campaign in the history of the United States almost a decade ago. Around thirty deaths and more than 400 injuries have been linked to the malfunction of Takata’s airbags across the Atlantic.

Europe is beginning to measure the scale of the disaster. After several fatal accidents involving its C3 model, Citroën has initiated the recall of several hundred thousand vehicles. The French company and its parent company Stellantis are now under threat of a collective criminal initiative. A procedure which is distinct from group action, a system which is celebrating its tenth anniversary in France this year. And shows mixed results to say the least, according to Maria José Azar-Baud, lawyer and lecturer in private law at Paris-Saclay. Founder of the Observatory of Group Actions, she is a member of two structures in Portugal and the Netherlands acting as plaintiffs in European collective litigation.

L’Express: At the beginning of June, a group action was launched against Stellantis, which recalled several hundred thousand vehicles from the Citroën and DS brands as part of the scandal over defective airbags supplied by the Japanese equipment manufacturer Takata. What is the point of using this procedure in such a case?

Maria José Azar-Baud: The procedure opened against Stellantis is not a group action. The strategy of my fellow lawyer aims at a massive constitution of civil parties in criminal proceedings. This choice is due in particular to the fact that a lawyer cannot initiate a group action. Group action is a very specific mechanism, open exclusively to associations approved in the field of consumer law. It can be initiated if the dispute concerns one of the five legal disciplines which are consumption, health, the environment, the protection of personal data as well as discrimination, particularly at work, hence the fact that unions can initiate a group action on this last question.

In the present case, the individual files of those who adhere to the platform deployed by my colleague will be presented at the same time or in installments. Everyone will be personally represented in court. It is a “collective initiative”, but not a collective action strictly speaking, nor a group action. This is an alternative to group actions which it must be recognized do not work well in France. The Observatory that I founded in 2017 reports 37 group actions initiated in total, including 20 in consumer law. Seven group actions were dismissed on the merits or declared inadmissible, four were concluded by a settlement and only one, the Dépakine affair, resulted in a favorable decision on the merits in the sense that Sanofi was declared responsible!

A parliamentary report submitted in 2020 reached the same conclusion, estimating that the system, born within the framework of the Hamon law on consumption in 2014, had “not been the source of significant progress in consumer defense “. What is the reason for this failure?

Group action does not work in France because it has “design flaws”. First, few entities can act and they do not always have the means, particularly financial, to do so. A group action requires costly expertise, communication and membership campaigns, specialized lawyers and, if possible, competent in comparative law because disputes cross borders.

Then, the subject of group action is currently too narrow: the field must be transversal and allow the compensation of homogeneous individual damages whatever the subject (competition, fundamental rights, etc.). The “opt-in” system is finally ineffective. To benefit from the decision, people must join the process after many years. The notion of “opt-out”, that is to say a system in which the group includes all those who are in the same situation, except those who decide to exclude themselves, would make it possible to improve access justice, the efficiency of the legal system and the deterrence of illicit practices.

More generally, the legal procedures are far too long, for example, Sanofi was declared responsible in the Dépakine case after five years and it is only following such a decision that the judge opens the membership period, which will allow victims to request to be part of “the group represented” by the requesting association. However, since Sanofi has appealed, this deadline has not even started to run yet… Not to mention that the compensation per person is very low: who will join for a few tens, or even hundreds of euros? Who will be able to prove their damage after ten years of proceedings? These considerations are likely to dissuade associations from acting and individuals from joining, which creates a vicious circle. Group action has been adopted at least in France, it is time to reform it. However, it works well in other European countries.

What lessons can be learned from other European countries?

One of the difficulties in France consists of the capacity of associations to finance their costs. I speak regularly in Portugal and the Netherlands. The approach is entirely different. On the one hand, collective actions are often financed by third party funders of the trials, which makes it possible to support procedures which can cost millions of euros as well as the hazard inherent in any legal trial.

On the other hand, European countries where group action works rely on the “opt-out” system. This amounts to protecting a majority, whereas in France only a minority of people will be able to ultimately benefit from the procedure. This changes the balance of power with companies.

The strong supervision of restrictive group action in France has often been presented as a means of combating the alleged abuses of class actions in the USA. What do you think ?

I think this is a fallacious argument. The supposed abuses of class actions have nothing to do with the mechanism of collective action but with the modalities of the judicial system. We blame the class actions US courts overly large judgments, often leading to inappropriate confusion with punitive damages. There is criticism that performance fees are too high for American lawyers but they are often agreed within the framework of transactions and in France such practices are prohibited. Finally, if a class action reaches the “trial” stage in the United States, it will be judged by a popular jury. However, this institution is little known by French courts which have to deal with group actions.

In the Netherlands and Portugal, as well as in the United Kingdom, group actions work and have not given rise to excesses. We must give weight to group action in France. I don’t see why in France the consumer would be left behind.

Last year, a text revising group action was adopted by the National Assembly before being rejected by the Senate. What is your opinion of what was proposed? What do you think are the possible areas for improvement of the system?

For group action to work in France, the scope of action must be universal, broaden the spectrum of people who can act in ad hoc associations, set up the “opt-out” for cases where damages are similar and encourage the financing of lawsuits by third parties. If the National Assembly’s 2023 proposal contains positive developments in certain respects, the Senate returned to the main advances. It’s terrible because we’re back to the current results. In both cases, the “opt-in” remains required, which is entirely ineffective for small disputes.

In addition, the proposed law aimed to transpose a European directive on representative actions to protect the collective interests of consumers, as 19 of the 27 member states have already done. France has only notified the European Commission of a partial transposition thanks to pre-existing rules on group actions. A Joint Commission was to decide on the discrepancies between the text of the National Assembly and that of the Senate. However, there was no public information in this regard before the dissolution of the National Assembly. Even less now.

.