For about a month and a half, Russia has been constantly on the agenda due to the developments regarding the invasion of Ukraine. However, the country has also harbored many mysteries since the Cold War years. One of them is the radio called MDZhB, which no one has been able to decipher. Not to mention the creepy sounds coming from the radio, which is accessible to everyone…

In the middle of a marshy land in Russia, St. Not far from St. Petersburg, there is a rectangular iron gate. Behind its rusty bars are radio towers, abandoned buildings, and power lines surrounded by a dry, stone wall. This place holds a secret dating back to the heyday of the Cold War.

This is believed to be the headquarters of the unknown radio “MDZhB”. For the past 35 years, it has been broadcasting a dull, monotonous sound 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Every few seconds, a second sound is added to this sound, such as the foghorn of a ghost ship, the initial buzz then continuing.

Once or twice a week, a male or female voice says Russian words like “agronomist” or “rubber boots”. There is nothing else. No matter where in the world, anyone who tunes their radio to 4625 kHz can listen to this broadcast.

It’s so mysterious it’s like it was designed specifically for conspiracy theorists. The radio station has tens of thousands of followers who affectionately call it “Buzzer”. Just like two other radio stations called “Pip” and “Squeaky Wheel”. As their fans themselves admit, they don’t know what they’re listening to either.

In fact, nobody knows what this radio does. “There is no information in the signal,” says electronic intelligence systems expert David Stupples of the City University in London.

WHAT’S HAPPENING?

The frequency is thought to belong to the Russian army, but the Russian army has never acknowledged it until now. Radio began broadcasting at the end of the Cold War, at a time when communism was in decline.

Today it broadcasts from two different locations: from this location in St Petersburg and from near Moscow. Oddly enough, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, instead of shutting down, radio’s activities suddenly accelerated.

Theories about what the buzzer does are incessant. It is even said that its purpose is to be in contact with submarines or to communicate with aliens. One theory is that if one day Russia were attacked by a nuclear weapon, that broadcast would shut up and automatically trigger a retaliation. Accordingly, the attacker and the target will destroy each other with nuclear weapons.

WHAT ARE THE FEATURES OF THE SIGNAL?

This possibility is actually not as strange as it might seem. During the Soviet Union, a system was developed to search for signs of life or traces of nuclear conflict by scanning broadcast frequencies. This system, known as the “dead hand” in the West, was later turned into a computer system that would trigger retaliation in the event of a nuclear attack. Worryingly, many experts believe it may still be in use.

As Russian President Vladimir Putin put it, “no one survives” in a nuclear war between Russia and the United States. Is Buzzer avoiding such a possibility?

In fact, there are some clues that the signal itself gives. Like most international radio broadcasts, Buzzer broadcasts on a relatively low frequency known as shortwave. Compared to local radio, cell phone and television signals, fewer waves pass through a single point per second. Therefore, radio waves can reach much farther.

While it may be difficult to listen to a local radio such as BBC London from a neighboring area, shortwave radios such as the BBC World Service reach many listeners from Senegal to Singapore.

However, both stations broadcast from the same building.

High-frequency radio signals travel in straight lines, disappearing when they hit obstacles or reach the horizon. Short-wave radio signals, on the other hand, can bounce off charged particles in the upper atmosphere and travel thousands of kilometers away by zig-zagging between the earth and sky.

Which brings us back to the “Dead Hand” theory. As you can imagine, shortwave signals are extremely popular. Today it is used in ships, airplanes, and transcontinental military communications across the seas and mountains.

However, there is an issue that needs attention. The short wave is like waves on the ocean. It has its ups and downs. It rises during the day and descends at night. If you want to ensure that your broadcasts are heard from the other side of the world, especially if you aim to signal a nuclear war, you need to change the frequency according to the time of day. The BBC World Service does this. But Buzzer doesn’t.

Another idea is that the radio station could be used to determine how far away the charged particle layer is.

“The longer it takes the signal to go up and down, the higher it is,” says David Stupples, electronic intelligence systems expert.

Buzzer is not like that. In order to calculate the height of a sheet, the signal must have a certain sound, like a car alarm starting to shout. Stupples states that such signals are not at all similar to the sound that Buzzer broadcasts.

A RADIO LIKE A BUZZER CHANNEL MORE

Interestingly, there was another radio station very similar to Buzzer. Broadcasting from the mid-1970s to 2008, this radio could be heard from the other side of the world, just like Buzzer. Just like Buzzer, it was broadcasting from an undisclosed location, from a place thought to be in Cyprus. Again, just like Buzzer, his broadcasts were odd.

Playing the head of the English folk tune “Lincolnshire Poacher” every hour, the radio repeated it 12 times, then a mechanical female voice, with a high English accent, a group of five digits “1-2-0-3-6”. He was reading numbers.

It’s helpful to go back to the 1920s to understand what was going on. At the time, the All-Russian Cooperative Company, simply referred to as Arcos, was an important trade body responsible for overseeing commercial transactions between Britain and the Soviet Union. Or at least, it was said to do so.

In May 1927, England raided the Arcos building in London after a British agent saw one of his officers enter a communist news office in London. The basement of the building was full of devices to detect intruders, and a secret room with no handle was found on the door, where the workers inside tried to burn some documents in haste.

It might have been dramatic, but the British already knew that. The Arcos raid came as a surprise to the Soviets, who discovered that the main British intelligence service had been listening to them for years.

“It was a first-order blunder,” says Anthony Glees, director of the Center for Security and Intelligence Studies at the University of Buckingham. To justify the raid, the prime minister even read some telegrams deciphered in the House of Commons.

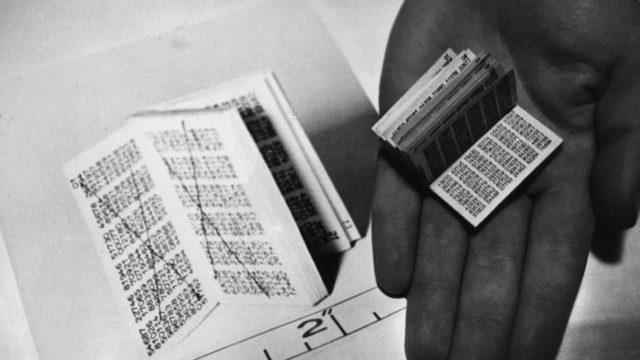

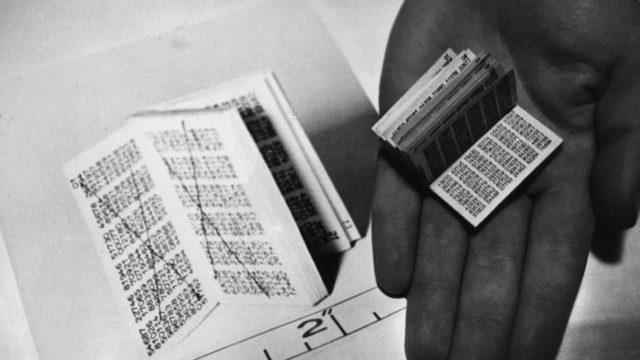

As a result, the Russians completely changed the way they encrypt messages. They switched to one-time passwords almost overnight. In this system, a random solution key was generated by the sender of the message and shared only with the person who would read the message. As long as the key was truly completely random, it was impossible to crack the cipher. The Russians no longer had to worry about who could hear their messages.

At this stage, “radio stations broadcasting numbers” came into play. They were broadcasting encrypted messages to spies all over the world. Soon, even the British resorted to the same method, based on the “if you can’t beat it, do the same” mentality.

Generating a completely random number is actually quite difficult, since the system trying to do it would avoid certain things, so it would be easy to guess the opposite of what is intended. Instead, officials in London came up with an ingenious solution.

They hung a microphone from the window in Oxford Street, the capital’s famous shopping centre, and recorded the traffic. “A bus could honk at the same time a police officer was shouting,” says Stupples. “It was a unique sound that could never be repeated.” Then they would take that and turn it into a random password.

Of course, that didn’t stop anyone from trying to crack the password. During the Second World War, the British realized they could actually decipher messages – but for this they had to get their hands on the one-off notes used to encrypt them.

“We discovered that the Russians were using old sheets of disposable notebooks instead of toilet paper in military hospitals in East Germany,” says Glees, head of the Center for Security and Intelligence Studies. British intelligence officers soon found themselves rummaging through Soviet sewers.

NORTH KOREA ENTERS THE STAGE

This new communication channel worked so well that such radio stations were opened all over the world without much delay.

These stations had colorful names like “Nancy Adam Susan”, “Russian Sayan Man” and “Cherry Ripe”. Buzzer fits into that category, at least in name.

Shortwave radio broadcasts were also the reason for some arrests made in the United States in 2010. The FBI, the American Federal Bureau of Investigation, reported that it has crashed a secret network of Russian agents who are said to be receiving encrypted instructions, specifically from the shortwave radio broadcasting on the 7887 kHz frequency.

Now North Korea has also stepped in. On April 14, 2017, the Radio Pyongyang announcer broadcast a poorly disguised military message, “I’m presenting an assessment of the open university’s core information technology courses for reconnaissance agents number 27,” followed by a series of page numbers (Page 823, page 957′) that look very much like a cipher. No. 69 in

It may come as a surprise that numbering stations are still used – but they have a significant advantage. While it is possible to guess who is broadcasting, it is impossible to know to whom the message was sent, as anyone can listen to the broadcasts.

Cell phones and internet may be faster, but when you open a text or email from a known intelligence agency, you can be detected.

DOES IT TURN INTO RADIO ONLY IN THE TIME OF CRISIS?

It’s actually a tempting idea for Buzzer to broadcast messages to Russian spies around the world, but there’s a catch. Buzzer has not published any numbered messages so far.

With a one-time note system, many things can be deciphered, from passwords to parasitic conversations. “If the phone call is encrypted, you’ll hear something like ‘…enejekdhejenw…’ but from the other end it sounds like normal conversation,” Stupples says. However, such an application leaves a trace on the signal.

What is done to send information from the radio is to adjust the wavelength and spacing of the transmitted waves. For example, if two low waves in a row mean X, then three waves broadcast at very short intervals can mean Y. When the signal is used to transmit information, it is bumpy like an electrocardiogram printout, rather than regular, evenly spaced waves like the waves emitted when a stone is thrown into water.

Buzzer’s signals are not like that. Instead, there are those who believe the station has two functions. The tone it broadcasts constantly is a sign that says “this is my frequency, this is my frequency…” to prevent others from using it. In times of crisis, for example, if Russia is invaded, it will become a station that broadcasts numbers.

It will then be able to instruct spy networks around the world and military forces in the country’s most remote areas. After all, Russia is a country about 70 times the size of England.

It seems that they are already practicing. Listening to the station from his home in a Baltic country, radio enthusiast Māris Goldmanis says, “In 2013, they broadcast a special message, ‘COMMAND 135 OUT,’ it was said that it was a test message to be ready for war.”

The mystery of the ghostly Russian radio The mystery of the Russian radio may have been solved. But if his fans are right, let’s hope the monotonous buzz whose silence would trigger nuclear retaliation never ceases. (BBC Turkish)