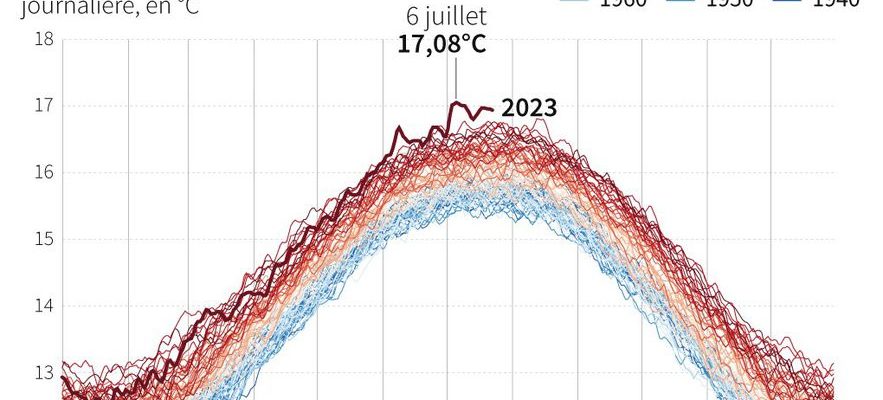

After a succession of atmospheric and sea temperature records, a new absolute reference is falling. According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the European institution Copernicus (which studies climate change), July should be the hottest month ever recorded on the planet. The data, which will be published during the monthly bulletin on August 8, shows that it is now “extremely likely” that July will be exceptionally warm.

In fact, for several weeks the curves of the various indicators have been panicking, dropping from the averages, and flying over even the most extreme readings. Looking at the average daily world temperatures, the curves of temperature anomalies since 1940, or even the thermometric readings in the North Atlantic, everywhere these figures which come out of the curves, widen hallucinating differences under the effect of gas emissions at greenhouse effect due to human activity. “The era of global warming is over, place in the era of global boiling”, was alarmed on July 27 the Secretary General of the UN.

July 2023 will be the hottest month ever measured, surpassing the previous record of July 2019.

© / SABRINA BLANCHARD, JAN MROZINSKI / AFP

Does this mean that global warming is accelerating? The succession of records recently observed, as much as the intensity of the extreme events that global warming causes, could suggest a tipping point, or even a climate that has become “out of control”, exceeding the estimates of scientists. But the observations are in line with repeated forecasts by climatologists, the scientists say. “The different models we use had predicted these extremes, it was part of the range of possible forecasts… But that does not prevent us from being sometimes surprised”, concedes Fabio D’Andréa, CNRS researcher at the Laboratory of dynamic meteorology. “Climate change is a trajectory towards warming, this trajectory is rapid, but it is not accelerating”, agrees Christophe Cassou, climatologist, research director at the CNRS and at the European Center for Research and Advanced Training in Scientific Computing ( CERFACS).

More accurate projections

To predict climate change, scientists rely on models, a numerical simulation of the Earth produced by a computer comprising a multitude of natural and anthropogenic parameters such as CO2 emissions, atmospheric pressure variations, cloud movements or the increase in ocean temperature. To try to get as close as possible to reality, climatologists rely on groups of models, which determine an average in the different simulated climate trajectories. “An international database is used to analyze the results, under different scenarios. They are not all similar, with different consideration of the factors that can cause the models to vary: the greenhouse gas emissions scenario , the way we represent clouds, solar radiation…”, explains Sylvie Joussaume, research director at the CNRS and climatologist specializing in the study of the mechanisms of past climate change.

Over the past few years, these forecasting models have improved significantly, increasing their accuracy and thus confidence in the projections. This may explain in particular the difference between the projections of the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for 2018 and 2021. In 2018, IPCC scientists anticipated that the average temperature would exceed the planet by 1.5°C between 2030 and 2050, while the 2021 edition of the report indicated that this threshold could be reached “between now and 2040”, suggesting an acceleration of climate change compared to projections. Similarly, the geographical precision of the projections, which now focus on regional changes in the climate, has shown in recent years that certain parts of the world are experiencing faster warming than others. This is the case of Europe, which is overheating at twice the rate of the world average. “The records that we observe and which are broken with very significant deviations from the previous ones alert us: is it due to events of natural variability, or is it our models that have underestimated the warming in Europe? This is a subject of research and there is surely a bit of both, “recognizes Christophe Cassou.

Massively reduce our emissions

If the average temperature of the globe follows a trajectory in line with projections, the occurrence of extreme phenomena which have, by definition, a low probability, now seems more difficult to determine. “The scientific answer is that it is not possible, for the moment, to determine whether we are observing a rate of increase in the frequency or intensity of extreme events that exceeds our estimates”, warns Fabio D’Andréa. . The work of the IPCC is clear: in a context of global warming, extreme weather phenomena, such as heat waves, heavy rains, or droughts, will be more frequent and more intense. But in this global framework is added the internal variability of the climate, that is to say the natural evolution linked to the climatic systems. This share of internal variability statistically forms a “domain of possibilities” concerning extreme events, which evolves with the climate. “We realize at the moment that we have several effects of variability which reinforce global warming”, explains Christophe Cassou. The development of the El Niño phenomenon in the eastern part of the South Pacific Ocean may thus be partly responsible for the temperature record observed in July, as can the drop in winds in the North Atlantic.

“We are not yet close to any reaction of excitement and nothing proves that points of no return have been crossed”, recalled in an interview with the World, the American climatologist and geophysicist Michael E. Mann, director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University. A finding that calls for action, because without strong initiatives to reduce our CO2 emissions, these climate tipping points could well be exceeded quickly.