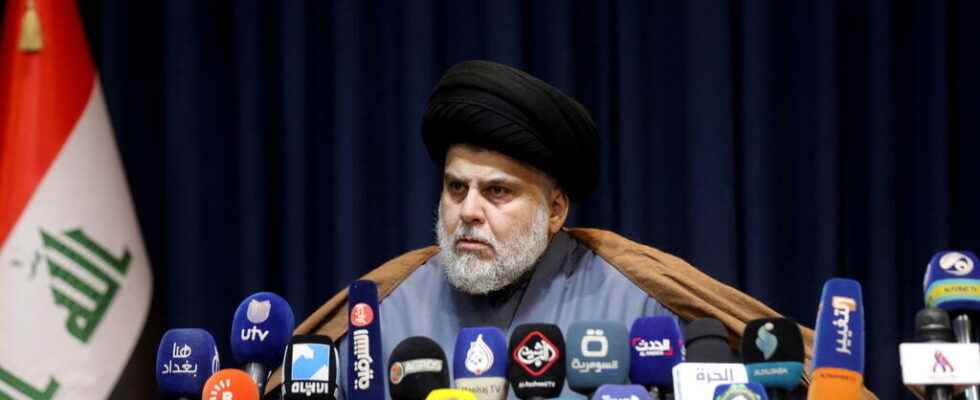

While for eight months the Iraqi Parliament has failed to form a parliament, Moqtada al-Sadr, leader of the majority bloc, created a surprise by announcing the resignation of all his deputies. Today, their main opponents of the ” Coordination framework “Shiites seem to want to take over the reins for the formation of a ” strong government “. Robin Beaumont, Iraq specialist at the Noria research center analyzes the situation for us.

RFI: The resignation of the 73 Sadrist deputies surprised everyone. What are the direct consequences of this political gamble ?

Robin Beaumont: What you have to understand above all is that Iraq is going through an unprecedented situation and everyone is a little bit in the dark today. Since the legislative elections of October 2021, there is therefore on the one hand the party of Moqtada al-Sadr which emerged as the big winner of the elections, and on the other the Shiite Coordination Framework. An alliance of a number of parties that are fairly quickly said to be pro-Iranian, let’s say they are indeed aligned with Tehran. This new parliament was unable to agree on the formation of a government. So the withdrawal, at the request of Moqtada al-Sadr, of its 73 parliamentarians, was presented as a way of trying to unblock the situation. The reality is that we have no idea what is going to happen.

There are two main scenarios. The first is to say that this is a political maneuver, that the Sadrist deputies actually have no intention of truly stepping down and that they will continue to occupy their seats. Their announcement would therefore only be a means of pressure to push for the formation of a government.

The second hypothesis is that Moqtada al-Sadr took a stand by withdrawing his deputies to force the Coordination Framework to find a solution on its own.

Today, we don’t really know what direction things will take, in particular because we are in an extra-constitutional situation, which is not provided for by any text. So there is no process to follow.

Does this situation represent an opportunity for Shiite parties, particularly those from Shiite militias who had refused to recognize their failure in the legislative elections?

In fact, we end up with a Parliament without its majority bloc. The Sadrists admittedly only represented two-thirds of the votes, but they were still the largest parliamentary bloc.

Today, MPs from what you call Shiite militias – let’s say from political and armed groups close to Iran – have more hands free. But they also have less legitimacy than if they had succeeded in forming a group, an agreement and a government with the Sadrist movement.

Today, Moqtada al-Sadr resumes his position as a protest leader, a role he is used to and in which he feels comfortable. He will not refrain from pointing out the fact that the new parliamentary majority, whether or not it manages to form a government, will be cut off from a large part of its legitimacy.

Moqtada al-Sadr, who calls in particular for the withdrawal of militias from political life, is now threatening to relaunch the social protest movement that marked history in 2019. Would the Iraqi population be ready to follow him?

The last major Iraqi protest movement is indeed the movement of october in 2019. Millions of people then challenged the country’s political system as it has existed since 2003. Today, the systemic problems of Iraq, corruption, the economic situation, the health situation are obviously still the same.

We are also entering the summer period which is traditionally the period of construction of protests, popular movements in Iraq, because it is extremely hot, the electric generators no longer work or work badly. Added to this today are concerns about food security and access to water. All the ingredients are there. The question now is whether the configuration of the popular forces is still the same? The answer is no. Most of today’s 2019 protest leaders have been co-opted by the political system. That is to say, they got themselves elected as independents in the last elections and were then co-opted or even bought by a number of parties. The others are tired, weary of this dispute, in particular because they realized that it had only resulted in hundreds of deaths and injuries without any political progress.

It is therefore difficult to imagine a resurgence of the October movement, of the ground movement. On the other hand, what is certain is that Moqtada al-Sadr has a social base which, for the most part, obeys him finger and eye. It therefore has the ability to organize a movement of protest and interference in the political process, and that is to be expected.

The resignation of Moqtada al-Sadr’s deputies is therefore not experienced as a failure by his voters who hoped at the base that the Shiite leader would take over the country and change things?

To answer this question, it is necessary to understand the position of Moqtada al-Sadr since 2003. He is someone who wants both to benefit from power and from the opposition. This ambivalence therefore leads him, for example, not to seek official positions himself in the Iraqi state system. He also avoids placing his men in positions that are too exposed. He understood that a ministerial post in Iraq comes and goes. On the other hand, his strategy consisted in placing trusted men in strategic posts in the Iraqi administration. To take a slightly classic expression: his strategy was to create a Sadrist deep state in Iraq. At the same time, he progressed at the polls.

But in the last elections, he found himself at the same time at the head of these strategic positions of the Iraqi administration and in the front line before public opinion. This double positioning was therefore very uncomfortable. It is difficult to build opposition legitimacy when you are the largest parliamentary bloc.

Because the impossibility for the parliament to form a government came partly from its desire to dominate the whole process. Until now, since 2003, Iraq has been operating by “ consensus governments “. Whatever the outcome of the elections, the deputies end up managing to form a government which willy-nilly represents most of the dominant forces in the country. This time, Moqtada al-Sadr wanted to break this dynamic by calling for the formation of a majority government. But he did not have a sufficient majority to make this decision alone. So he insisted on this principle without allowing the country to break out of the political deadlock.

Today, his decision allows him to place full responsibility for the blockage on his political opponents and to present himself as the one who sacrifices himself to get the country out of the impasse. In reality, it only shifts the problem by handing over the task to the rest of the political scene.