Wind turbines in front of refineries. Along the A15 motorway that crosses the island of Rozenburg, east of Rotterdam’s city centre, the tall propeller masts posed along the banks of the Old Meuse and the Scheur rivers frame the enormous industrial complex of Botlek and its dense petrochemical activity. A striking contrast, witness to the energy transition at work in the Netherlands. A few kilometers away, in the residential district of Rozenburg, four containers arranged on the edge of a football field also catch the eye. “Experts come from China, Japan, all over Europe to see what we have here,” enthuses Raymond van den Tempel, consultant for the Remeha group, a European heating system manufacturer. Its war chest: a low-carbon hydrogen production system to supply three boilers of a neighboring residential complex, developed with Stedin, the manager of the electricity and gas network in the Randstad region.

A world first, we are told, as well as a promise. The Netherlands, which has long focused its development on fossil natural gas produced since the 1960s on the gigantic gas field of Groningen, in the north of the country, is turning away from it today for both climatic and geological reasons. The exploitation of this reserve, which has caused many earthquakes in this region, must end in 2028 at the latest. His legacy is anything but negligible. Of the 8 million homes in the country, 92% are now heated by gas. The government’s objectives are ambitious. It has in fact undertaken to remove fossil resources from buildings by 2050 with a ban on new natural gas boilers from 2026. They must be replaced by greener sources, including heating networks and especially heat pumps, classic therefore running only on electricity or hybrids combining electricity or gas.

Hydrogen-heated villages

Stedin, he is trying to prove that gas of renewable origin will have its place in the equation, and in particular hydrogen. Further south, just under an hour’s drive from Rozenburg, in the municipality of Stad aan ‘t Haringvliet, the manager wants to heat a village of 650 buildings with hydrogen by 2025. In the meantime, he s is already trained by connecting a house, just to show locals that switching between technologies is safe. The work is not heavy, because based on existing pipes. The boiler operating with the miracle molecule and therefore stamped with an “H2” corresponding to its chemical formula, also resembles unmistakably conventional tools.

A challenge remains on the smell of hydrogen, which does not smell like its fossil cousin and contrary to popular belief. “Currently, we odorize natural gas with chemical sulfur compounds to identify leaks. But sulfur damages fuel cells, so we have to find another process,” notes Tessa Hillen, project manager for Rozenburg at Stedin. On this subject, the Dutch are working in particular with the French gas distributor GRDF. Nothing insurmountable in that, to hear the leaders of the two groups. “The subject that comes up in the mouths of the inhabitants is not the technology itself, or the security issues, but rather that of the price”, adds for his part Tjebbe Vroon, energy transition analyst for the manager and who makes the visit. on this Tuesday in November.

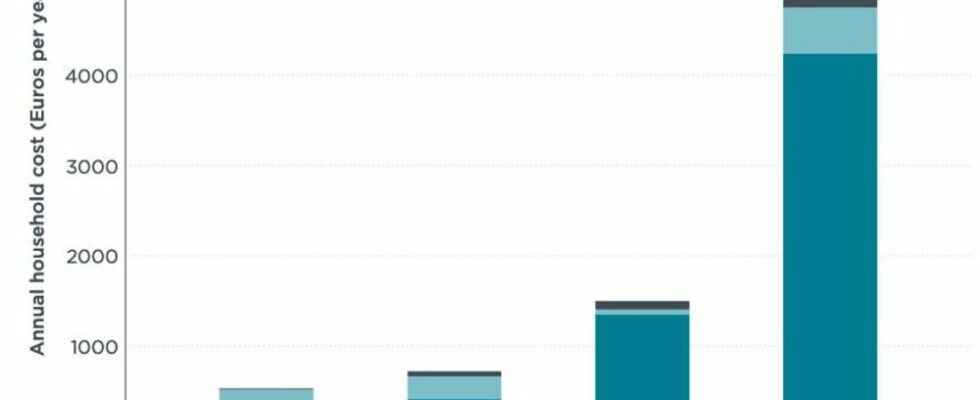

The energy crisis has obviously been there. In a country addicted to gas, the price of which has tripled in the space of a year, the question becomes central. As such, a study by the International Council on Clean Transportation carried out in 2021 on the decarbonization options for Dutch households in 2050 suggests that the most relevant option, economically speaking, remains that of a 100% electric heat pump, including ahead of the hybrid solution mixing heat pump and boiler high-performance annex that would run on hydrogen.

Average cost per household of a heating installation according to the technology used, in the Netherlands in 2050

ICTT

A gap that could in theory justify a switch to “all electric”. But on the spot, it looks more and more like a chimera. Since 2018’s aggressive rhetoric to ban gas wherever it lurks in homes and buildings across the country, the Dutch government seems to have taken a step back. Sjoerd Delnooz, of the consulting firm Kiwa Technology, believes that there is still room for gas in the country, in particular because of the “unsuitable infrastructure” for the transition to all-electric.

The all-electric mirage

The main criticism lies in particular in the congestion of the network linked to the massive electrification of the country. The proportion of electrons in the mix should increase from 20% to 50% by 2030. However, the accelerated development of intermittent (solar and wind) and decentralized renewable generation, combined with the rapid growth of digitization, but also electrification in industrial, mobility or building uses (sales of heat pumps increased by 50% between 2020 and 2021) put the network under tension. In some parts of the country, large industrial consumers cannot request new connections to the electricity grid and the grid is expected to be live at least until 2028 according to data from Tennet, the local TEN.

It is therefore easier to understand why the Dutch government favors hybrid systems combining electricity and gas. As well as the interest of the French group GRDF, whose general manager Laurence Poirier-Dietz made the trip on Tuesday. “They are in a balanced approach to energy and not ideological issues, taking the best of both worlds”, smiles one of the leaders of a French gas sector who has been fighting for months to defend the idea of an energy mix. balance.

Still, in France as in the Netherlands, the equation for the gas industry is actually the same: go green or disappear. The Netherlands has set the share of green gas in the network at 20% by 2030. This will be based on the production of biogas from organic matter or waste, but also synthetic methane as well as hydrogen. The country relies heavily on the last of these three gases. Both for the residential sector, but also for a very demanding industry. The country’s current gas network and its 136,000 km of pipelines should be put to use, through an operational national network by 2026. This makes it possible to contain costs. Firmly anchored in the heart of the European megalopolis, although a small state, the Netherlands is also toying with the idea of becoming a giant in the export of this gas to the Old Continent.

A new gas revolution

And the enthusiasm of some overflows. In a recent report submitted to the local government, Jörg Gigler, an independent consultant, saw in hydrogen a second gas revolution after the discovery of the exploitation of the Groningen deposit. “It’s a dynamic that will not stop”, promises the expert. In the meantime, there are many projects. Although it is now Europe’s second largest producer with 9 million cubic meters of hydrogen, these molecules are produced from fossil fuels. To remedy this, the Netherlands is counting on the capture and sequestration of CO2 at the outlet of the factory producing hydrogen. But the process needs to mature.

In the longer term, low-carbon electricity (renewable or nuclear) can also make it possible to run the 4GW of electrolyzers that the country intends to deploy by 2030. However, capacities remain limited for a country of this size, where the question of the acceptability of wind power is central, and where conflicts with other uses of electricity could arise. Also, the country already knows that it will have to turn to imports, having the capacity to produce this green gas in abundance. Entering thereby into a global competition that already promises to be fierce, because nothing, or almost nothing, still exists today.