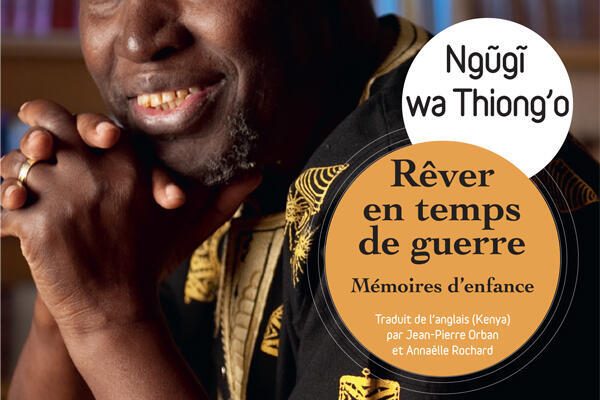

Dreaming in war is the French title of the childhood memories of the novelist and playwright Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Octogenarian, the writer restores in this first volume of his Memoirs the oppressive atmosphere of colonial Kenya where he grew up and which was the breeding ground for his literary and activist commitment. The birth of his vocation as a writer is the theme of this second part of the chronicle that Tirthankar Chanda devotes to this giant of African letters. (Rebroadcast)

“ When, years later, I read TS Eliot’s verse where it is said that April is the cruelest of months, I remembered what had happened to me one day in April 1954 in the cool of Limuru, in the heart of this region which in 1902, another Eliot, Sir Charles Eliot, then colonial governor of Kenya, had taken over by renaming it White Highlands. The past then came back to my memory as vividly as if it were present again. »

So begins Dreaming in warthe first volume of the Kenyan writer’s romantic memoirs Ngugi wa Thiong’o. These are also very political memoirs, as the cited extract illustrates. Here, Eliot is not just the name of a poet. It is also that of a British governor whose mandate at the beginning of the last century remains associated in Kenyan history books with colonial spoliations. This rapprochement of the political and the poetic is what makes the Kenyan’s entire literary work unique, considered with Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka as one of the founding and fundamental fathers of African English-speaking.

Ngugi is not only a novelist, but also a playwright, essayist, activist. His powerful and protean work has earned him imprisonment, exile, physical and verbal assault, as well as global recognition, with his name regularly cited as a potential Nobel Prize winner. The man, now 86 years old, who embraces dissident thought from Marx to Frantz Fanon, is the very example of a committed writer. This commitment is rooted in the childhood of Ngugi, the subject of the first volume of his memoirs.

An unwritten pact

The story begins at the time of the author’s grandparents who saw their country fall into the hands of the Germans, then the British, following the partition of Africa by the European powers at the famous Berlin Conference. , in 1885. As for the author’s father, to escape conscription during the First World War, he had to flee the hustle and bustle of the nascent Nairobi where he worked as a servant in a European family, to settle in more rural areas, in the center of the country.

Born in 1938, “ in rural tranquility » in central Kenya, Ngugi grew up in the oppressive shadow of British colonization. The exploitation, the spoliation, the repression of the separatists which affected the writer’s close and family entourage, constitute the very texture of these Childhood memories.

Remembering the little boy he was, Ngugi depicts his slow awareness of the injustices and brutalities of colonization. It is ” as if I were emerging from the mist », writes the author. The protagonist realizes the poverty of his family, the colonial domination and the helplessness of adults. One of his first memories is linked to the pyrethrum fields where his family sent him to help pick them. At the age of 8, he must earn his living. School will be his salvation.

“ I never imagined that I would one day be able to studyproclaims Ngugi. It was my mother Wanjiku, who could neither read nor write, who asked me one evening if I would like to go to school. The question remained engraved in my memory as school seemed, at the time, beyond my reach. In fact, everything I am today I owe to my mother. Women have always played a major role in my life. Just like the prominent place they occupy in the history of Kenya. They participated fully in the anticolonial resistance. It was women who literally held Kenyan society at arm’s length, preventing it from disintegrating. »

Ngugi likes to say that he never really understood where the determination his illiterate mother showed to ensure a proper education for her children came from. Still, it is to his obstinacy and his resourcefulness in raising the money necessary for registration and the purchase of the required uniform that young Ngugi owes his admission to the school. In one of the most poignant scenes in the book, the writer talks about his mother reminding him that they were poor and that at school, he might not eat every lunchtime. The teenager that he was had to promise her, writes Ngugi, that he was not going to make her “ ashamed just one day by refusing to go to school, because he was hungry or it’s difficult “. It was an unwritten pact between mother and son that was never to be broken.

A haven of peace

If the universe Magic » of the school appears in the book as the counterpoint to the turbulence that Kenya is going through, confronted in the post-Second World War period with a bloody cycle of independence demands and repressions, the school was not entirely a haven of peace. Ngugi recounts how the Kenyan school had become the field of ideological battles between the assimilationist current represented by the missionaries and the indigenous movement.

The war raged between these two visions of Africa. While in independent schools founded by enlightened Kenyans, teachers spoke of Africa as the continent of the black man, missionaries close to the colonial power taught a revisionist version of African history, celebrating the arrival of Europeans who would have brought peace, progress and civilization. They erased the conquests, the spoliations and the complete destruction of indigenous cultures. The climax was reached with the closure of the famous Kenya Teachers’ College who trained indigenous teachers. “ The hardest blow to collective morale wasNgugi remembers, when the colonial state decided to transform the grounds and buildings of the establishment into a prison camp where those resisting colonialism were hanged. »

Despite the acculturation that school represented for the student Ngugi, the pact that he had concluded with his mother one winter evening was never broken. It was even less so because alongside the trauma of the loss of his culture, the school allowed the teenager to discover his future vocation as a writer, by introducing him to the great classics of English literature. Great expectations by Charles Dickens and Treasure Island by Stevenson as well as other emblematic books will be his gateway to the world of the imagination. The little boy had obscurely sensed its existence in his early childhood, during nightly vigils in the hut of his mother’s co-wife.

“ My father had four wives, explains Ngugi. We called them “our mothers”. We gathered every evening in the hut of the eldest of the four. The latter was an outstanding storyteller. I was fascinated by the imaginary world into which she took us. The night was ideal for these storytelling sessions. Our mothers told us that daylight chases away stories. They returned home as soon as daylight broke and did not return until the day’s work was finished. It was only when I went to school and learned to read and write that I realized that you could tell stories whenever you actually wanted. I believe, however, that it was the nightly vigils around my storyteller mother-in-law that made me the writer I became. »

Dreaming in war ends with the departure of the protagonist for the prestigious Alliance High School where the rest of his education will take place. Sitting in the bus that takes him to his destination, the teenager does not yet perceive, through the mist that envelopes the morning landscape, the promise of the sumptuous writing life that awaits him. But, he does not forget to pay tribute to his mother, by renewing in thought their secret pact of “ dream, even in times of war “.

Dreaming in wartime. Childhood memories, by Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Translated from English by Jean-Pierre Orban and Annaëlle Richard. “Pulsations” collection, Vents d’ailleurs editions, 258 pages, 22 euros.