A lush oasis amidst a Grand Canyon landscape. At the beginning of December, temperatures were close to 30°C under the sun of AlUla, in the western Saudi desert, but this winter mildness did not slow down the teams of archaeologist Jérôme Rohmer. At the foot of monumental cliffs, French and Saudi researchers scrape every stone and scrutinize every channel of a fort dating from the 4th century AD, that is, three hundred years before the birth of Muhammad, the founder of Islam.

Soil studies have shown that these lands were cultivated in Late Antiquity, and French archaeologists are now trying to determine which people occupied the area in this pre-Islamic period. By identifying the place where the tribe threw their leftover meals, where all the food bones were gathered, the Franco-Saudi team was surprised to find no trace of camel bones. “Our most likely hypothesis is that of a food taboo, a people who would not eat this animal, explains Jérôme Rohmer. In pre-Islamic times, many Jews and Christians, including certain sects such as the Copts, did not eat camels. It could be the missing link between antiquity and the Islamic period.” Jewish tribes populating the protective kingdom of the holy places of Islam? A simple hypothesis to be handled with care, even in 2022. “We still have no certainty, specifies the French specialist. And that is the objective of our research.”

Changing mindsets and the reputation of Saudi Arabia

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has discovered a passion for its history. Until now, any reference to the pre-Islamic period has remained taboo in the kingdom and it took the coming to power of the young Prince Mohammed ben Salman (alias MBS) in 2017, as reforming as he is authoritarian, to open the country wide to the archaeologists. “In Saudi Arabia, interest in archeology has long been … cautious, smiles Jasir Al-Herbish, executive chairman of the Saudi Heritage Commission. Research was done informally but, for four years and for the first time , we have a Ministry of Culture that is taking this work forward dramatically.”

To project his country into the post-oil era, MBS wants to change mentalities, but also the reputation of his kingdom, still at the bottom of the world ranking of respect for human rights. Essential to attract tourists and investors. “Saudi Arabia has long been perceived as the crossroads of civilizations, blows a Saudi researcher. We now want to be consecrated as the cradle of civilizations.” A new national narrative, written in part by the French.

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

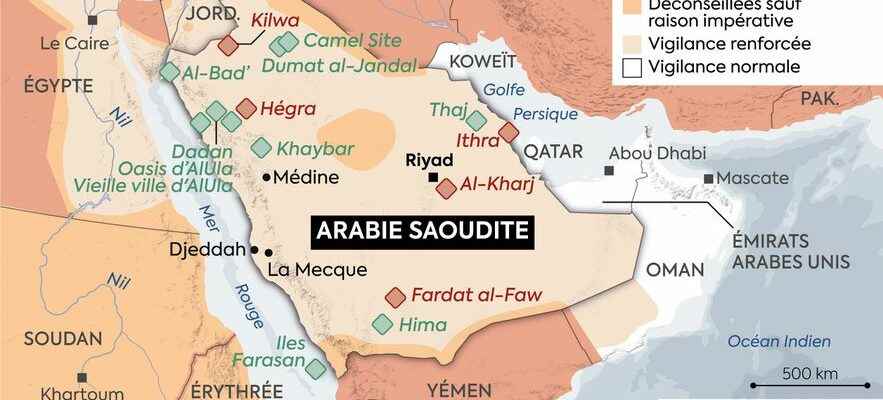

With 15 archaeological missions and hundreds of experts on site, tricolor archeology is by far the most present in the kingdom. “The French have offered archaeological missions for a very long time and have been able to infiltrate the slightest opening, as twenty years ago for the excavations in Hegra, underlines a French archaeologist. Trust has been created with the Saudis and, even if the English and the Americans try to position themselves, France remains in place.”

The turning point came in April 2018 when, during a visit to Paris, Prince MBS entrusted our country with the cultural and tourist development of the city of AlUla, a natural treasure in the middle of the desert, which has become one of the largest archaeological projects in the world. Thanks to the work of the French Agency for the Development of AlUla (Afalula), more than 120 French specialists take turns to decipher its ten thousand years of history. “France is a brother country, supports Jasir Al-Herbish. Its researchers have enabled us to register several of our sites as World Heritage Sites, and this cooperation will continue to grow.”

Ingrid Périssé, Archeology and Heritage Director of Afalula

In AlUla, the French are everywhere: in the middle of the palm grove, they have collected more than 53,000 objects making it possible to retrace the millennia of history of one of the most important oases in Arabia. A little higher, in the Old City, wearing construction helmets, they excavate dozens of abandoned buildings, which for centuries were a resting place for Muslim pilgrims between Damascus and Mecca. According to the most recent discoveries, the city would have been frequented since the Middle Ages. “Unlike other places of exceptional historical richness, particularly in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia looks like a blank page,” enthuses Ingrid Périssé, archeology and heritage director at Afalula. not a hundred and fifty years of research and scientific writing. We are a bit like Greece or Mesopotamia of the 19th century, everything remains to be written!”

French and Saudi archaeologists study the old town of AlUla, where Muslim pilgrims have stopped for centuries.

© / Afalula

Near these excavations, archaeologists have to deal with the “new” Saudi Arabia and its goal of attracting 100 million tourists a year. Already, a few groups of wealthy travelers are flocking from Europe or the United States to admire the age-old beauty of AlUla. In the Old City, brand new restaurants are bringing in star chefs, souvenir shops are teeming and several hotels are being built. Archaeologists find themselves engaged in a race against time. “Originally, the Saudis wanted to raze the oasis of AlUla to build a tourist area, but we were able to convince them in extremis of the importance of what could be found there,” says one of the women. ‘between them.

In its frenzy of change, MBS is launching huge projects all over the country, between the futuristic city of Neom in the west or the “Red Sea Project” of seaside resorts on the south coast. “Our job is also to ensure that Saudi treasures are preserved, says archaeologist Guillaume Charloux, who worked on the sumptuous engravings of “desert dromedaries” in the north of the country. But everything goes very quickly here and the Saudis may find it difficult to manage so much information.”

For French archaeology, the opening of Saudi Arabia looks like an unexpected El Dorado. Very present in Syria, the French no longer have access to their local excavations since the beginning of the civil war in 2011. Similarly, in Iraq, Afghanistan or Yemen, their work is now almost impossible. “Archaeologists are a bit like refugees, they migrate according to political situations, notes researcher Pascal Butterlin. As such, the Saudi openness is excellent news.” “It’s a real breath of fresh air for French archaeology”, confirms Guillaume Charloux.

The profession also benefits from the changes in society made in recent years by the Saudi kingdom: end of the compulsory veil for women or the obligation to travel with a guardian, creation of tourist visas in 2019, appearance of cinema and concerts… “The atmosphere reminds me of Syria in the 1990s, at the time still cut off from the world”, testifies Ingrid Périssé. On the French side, we are aware of certain taboos in Saudi society, particularly on the Jewish presence in the country in the past, and we leave the initiative to local researchers to reveal this kind of discovery. “On the question of values, it is sometimes difficult to work in Arabia”, confides an archaeologist. Despite everything, these dozens of researchers dream of the treasures of Saudi history and begin to fill its blank page.