In Rafah, in the south of the Gaza Strip, concern is intensifying at the same rate as the sound of bombs. In this town located just a few hundred meters from the Egyptian border, the Israeli army has stepped up its airstrikes campaign in recent days, hitting at least seven targets on February 8 alone. The day before, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu ordered the army to “prepare an operation” on the city, four months to the day after the start of his war against Hamas terrorists.

Faced with the prospect of an imminent ground assault, tension has risen a notch in this area where there are today more than 1.3 million Palestinians – the vast majority of whom are displaced, crammed into tents after having fled the fighting further north. “The humanitarian consequences of an Israeli offensive on Rafah would be catastrophic,” summarizes Hugh Lovatt, Middle East specialist at the European Council on Foreign Relations. “There are already problems on the ground with access to water and food and a lack of accommodation.” The cause is record overpopulation, far exceeding the meager capacity of the infrastructure on site.

Warning from Washington

Aware of the risks of worsening the humanitarian situation, the United States indicated on February 8 that it would not support an operation which would take place “without serious and credible planning” concerning the management of civilians, warning of a possible “disaster” . The same day, Joe Biden himself described the Israeli response as “excessive”. If, on February 9, the Israeli Prime Minister asked his army to submit a “combined plan” for the “evacuation” of civilians from Rafah, the operation promises to be particularly complex. “A new transfer of Palestinians to the north is not realistic, to the extent that the infrastructure has been destroyed and can no longer accommodate more than a million people,” notes Hugh Lovatt.

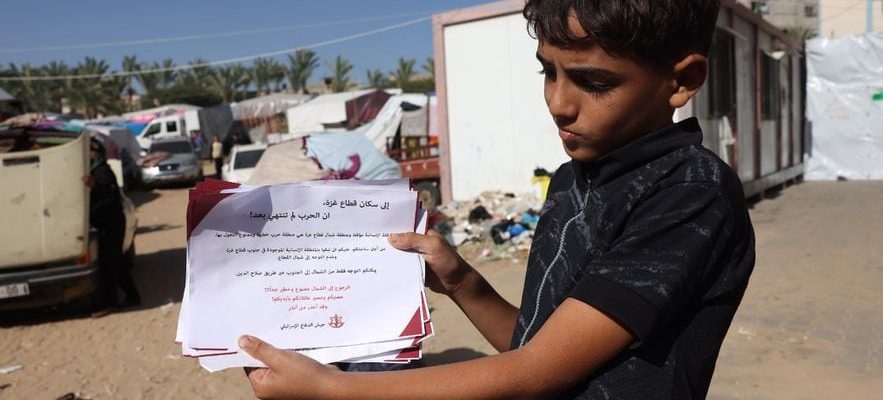

Another difficulty: the technique aimed at warning the population of the strike zones, ahead of the bombings, showed its limits during previous offensives on the towns of Gaza or Khan Younes. “The Israeli army will probably take the usual precautions, such as sending leaflets or SMS messages detailing targeted areas, but they are not very effective,” explains Amélie Férey, coordinator of the defense research laboratory at the Center for Security Studies. Ifri. We know that people do not necessarily receive this information on their phone, due to lack of network or electricity, and that they do not always trust it.”

A Palestinian child shows an Israeli army leaflet ordering Gazans not to return to the north of the territory, November 24, 2023

© / afp.com/MOHAMMED ABED

Likewise, the population’s ability to evacuate combat zones is not guaranteed either. “In this type of configuration, we find elderly people, or sick people, children, whose mobility is very reduced, points out General Nicolas Richoux, former commander of the 7th armored brigade. In the north, not everyone is left, and many civilians found themselves in a combat zone.”

Risk of regional destabilization

An offensive on the city would be all the more dangerous as the Rafah border post, on the border with Egypt, plays a crucial role in the delivery of humanitarian aid, vital for the population. “It is difficult to imagine how it could continue to operate in the event of an offensive in Rafah,” notes Hugh Lovatt. Beyond that, there is also the risk of greater regional destabilization. “If the Israeli operation sows panic among the population, there is a real danger of seeing many Palestinians try to cross the border into Egypt,” continues the researcher. However, the Egyptian government has been very clear on the fact that it refused any movement of Palestinian refugees into its territory.” A scenario considered in Cairo as a political and security threat.

For the moment, however, the Israeli government is showing no signs of wanting to pause its offensive. “Victory is within reach. It cannot be counted in years or decades, it is a matter of months,” declared Benjamin Netanyahu on February 7, rejecting Hamas’ truce proposal, described as “delusional.” .

“Every terrorist hiding in Rafah must know that they will meet the same end as those in Khan Yunis and Gaza City,” Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant insisted two days earlier, after presented the city as “the last bastion of Hamas”. “It is impossible to wage a war among the population without causing significant collateral damage,” summarizes General Richoux. “Deciding to do it despite everything means accepting the fact that there will be losses among civilians.” According to figures released on February 9 by the Hamas Ministry of Health, at least 27,940 Palestinians have died in the Gaza Strip since the start of the conflict.

.