Punches in the face, knees in the stomach. The attacker pulls out an electric baton and threatens (in Mandarin): “If you try to run away, I’ll kill you.” He then drags his victim in front of the camera: “I’m in Cambodia, I’m not in China, says the young man in tears, his voice broken and his nose bleeding. Please, dad, send some money to set me free.” The ransom note is dated last August. The man who shows us these images via encrypted messaging was also beaten while he was in Cambodia, a prisoner in one of the many places of confinement held by the Chinese triads in Southeast Asia. Last year, he managed to escape, in the middle of the night, by climbing a wall.

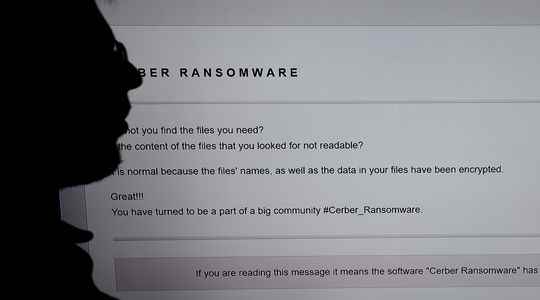

A survivor of this hell where he spent four months, he now leads a network of volunteers who try to help victims of human trafficking, in association with the Hong Kong NGO Branches of Hope. “The process is always the same, explains our witness. The targeted person responds to a job offer: a computer technician or Internet marketing position. The position is based in Cambodia, the salary attractive. But once he arrived there, his passport was confiscated, he was asked to pay a ransom ranging from 3,000 to 15,000 US dollars, then he was forced, twelve hours a day, to set up online scams (scams with fake profiles, bogus investments, cryptocurrencies or online games….” This is what recently happened to a young Chinese from Guangxi, a former home delivery man, who thought he could earn $3,000 a month working for an Internet site, confides a Cambodian journalist who investigated the subject. The only skills required were knowing how to speak Mandarin and how to use a computer. He found himself kidnapped in the Cambodian coastal town of Sihanoukville.

The Covid-19 pandemic, which has caused unemployment to skyrocket, is pushing many Chinese to accept these too-good-to-be-honest job offers. “It is estimated that at least 30,000 people were victims of these enslavements in Cambodia alone, assures Jason Tower, representative in Asia of the United States Institute for Peace. Every day, hundreds of job postings on social media attempt to attract Chinese workers to Cambodia, Burma and Laos, where they find themselves ensnared by these criminal organizations.”

“The pandemic has forced ‘crime lords’ to adapt”

When Xi Jinping took power in Beijing a decade ago, he launched a massive hunt for organized crime, not only in mainland China, but also in Hong Kong and Macau, where casinos have long been used to launder money. dirty. The triads have retreated further south, where they have set up online casinos that have reportedly brought in more than $145 billion in the past two years, according to official figures cited by Chinese state media. From casinos, they then moved on to pornography and online scams, cryptocurrency sales and fraudulent investments.

“The pandemic has forced ‘crime lords’ along the Mekong to adapt and innovate,” Jeremy Douglas, of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, told Reuters. clandestine agents they operated in the border areas lost their customers when the borders were closed. They reacted by accelerating the switch of their activities to the Internet and to electronic fraud from call centers, which constituted new sources of income. These kidnappings have grown to such an extent that it has become a problem in the region.”

Beijing had to bang its fist on the table and put pressure on the countries concerned to intervene, release its nationals and close these underground gambling dens. Since 2020, Chinese police say they have extradited more than 130,000 people responsible for these operations and closed 24,000 online casinos. But most mafia bosses have relocated to Burma and Laos or have taken Cambodian nationality to escape prosecution.