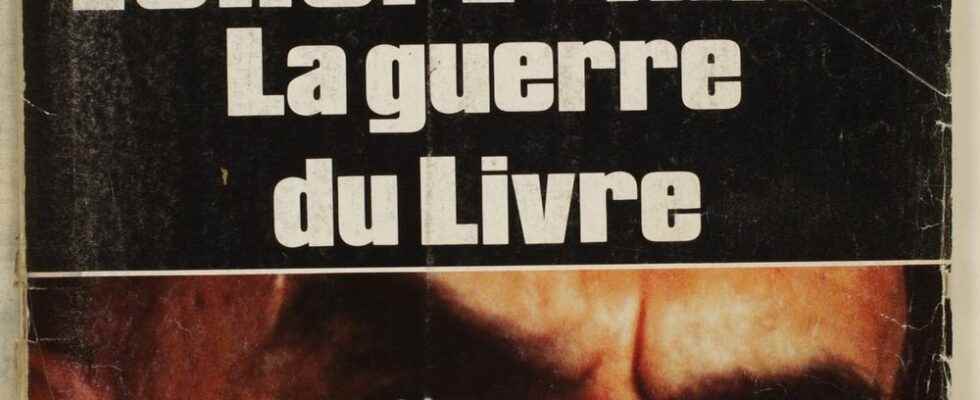

It was on February 14, 1989 that Rouhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader in Iran, issued the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, asking “all zealous Muslims” to execute the author of the satanic verses. A few days later, L’Express devotes its first cover to the Rushdie affair, under the title “Europe-Iran, the book war”: interviewed by Elie Marcuse, Salman Rushdie speaks about the fatwa “of a pretext to kill”.

The Express

In 1996, when his first novel after The Satanic Verses, he exposes his joy in front of Christine Ockrent who meets him in London for L’Express. “What I savor above all, thanks to the verb and to writing, is my victory over fate and the stupidity of men. I was so fed up with my character as the” most famous writer of the world” whose books, or almost no one, had read! […] I finally feel free from politics. My only weapon, the strongest, is again literature. From the ordeal of being pursued by a fatwa I learned at least one lesson and one chance: the writer’s imperative duty to fight for freedom.”

Themes that he will have the opportunity to develop, during an interview with the cultural journalist Thierry Gandillot in September 2005. Asked about the consequences of the fatwa on his writing, here is Salman Rushdie’s answer:

“It made me more determined than ever to carry on as I had always done. Go my own way. I didn’t want to write fatwa books: neither scary, nor sensational, nor cautious, nor self-censoring, nor circumstance. Just to continue to be the writer that I would have been. And I think that in the end, that’s what I did. But, of course, if something important happens in life of an author, it affects him.”

Affected, no doubt, but not silent. In 2015, a few months after the killing of Charlie Hebdo, he gives an exciting interview to Philippe Coste, correspondent for L’Express in New York, in which he does not mince his anger. “More than twenty-five years after The Satanic Verses, it seems that we have learned the wrong lessons. Instead of deducing that it is necessary to oppose these attacks against the freedom of expression, we believed that it was necessary to calm them by compromises and renunciations. […] We can deplore a return of political correctness in intellectual circles.

For Salman Rushdie, it is urgent “to put an end to this taboo of so-called “Islamophobia”. I repeat. Why can’t we discuss Islam? It is possible to respect individuals, to preserve them intolerance, while displaying skepticism towards their ideas, even criticizing them fiercely.”

Committed, the writer, despite the fatwa, threats and hiding, has always refused to live cut off from the world. As he confided in 2003 to François Busnel who had met him for L’Express in New York, there was no question of stopping speaking or writing.

“Risking your skin every day is the price to pay to live free. But, if I start thinking that a weirdo can shoot me at any moment, I won’t live anymore. I learned to grow up without fear for a simple reason: fear paralyzes action, and I want to act.”