In 2021, Amandine Simard connected to the Parcoursup platform the beating heart. The high school high school student discovers that she is admitted to the very selective “multidisciplinary cycle of higher education” of Henri IV. “Passed the joy of seeing my first wish granted, quickly asked itself to know where I was going to live. I did not expect the obstacle course who was going to follow!”, Continues the girl who grew up in a rural commune in Ariège. In the first year, his stock market status did not allow him to get Crous accommodation. She ends up finding a 16 square meter studio and finances her monthly rent of 700 euros thanks to a student loan. “Subsequently, I ended up winning the case with Crous but my journey was chaotic! I had to come back to the charge many times. I almost abandoned everything on several occasions,” says Amandine Simard, now written in Master.

His case is far from isolated. According to a survey by the Institute Opinion Way, unveiled in 2023, 17 % of young people aged 18 to 24 have already given up their studies for lack of roof under which to take shelter. “It has become the first obstacle to equal opportunities. The fact that training places are concentrated in metropolitan areas, where the real estate crisis is the most acute, penalizes young people who are most distant,” alerts Bixente Etcheçaharreta, founder of the association of territories with major schools. Already in 2007, the latter who lived in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques, had himself had to give up joining the preparatory class of the Henri IV high school where he had been accepted. “There was no more room for the boarding school and my family could not afford to help me,” he said. In almost 20 years, the situation has only worsened. In its annual report, published on March 19, the Court of Auditors emphasizes “this problem today weakly taken into account by public policies”: in 2020, rural areas only had 20 % of higher education graduates, compared to almost 32 % in mainland France. The question of accommodation represents one of the main brakes.

And Bixente Etcheçaharreta, regional advisor to the New Aquitaine, to advance the example of Pau: “A first cycle dedicated to medical studies was opened a few years ago. This allowed the students of Palois and the surroundings who could not afford to find accommodation in Bordeaux not to give up their dreams”. As in many other big cities, the rents are soaring in the prefecture of Gironde where Paying an average of 610 euros for a studio. “As part of reindustrialisation, the challenge is to train people according to the dynamics of the territories. This will inevitably go through a decentralization of the” “training offer, he continues.

“A two -hour door to door”

And Bixente Etcheçaharreta, regional advisor to the new Aquitaine, to advance the example of Pau: “A first cycle dedicated to medical studies was opened a few years ago. This allowed the students of Palois and the surroundings who did not have the means to find accommodation in Bordeaux not to give up their dreams “. As in many other major cities, the rents are blazing in the Gironde prefecture where it is necessary to pay on average 610 euros for a studio. Or an increase of 2.8 % between 2023 and 2024, over this same period, the number of goods to rent was reduced by 4.7 %, according to 4.7 % The Guy Hoquet observatory.

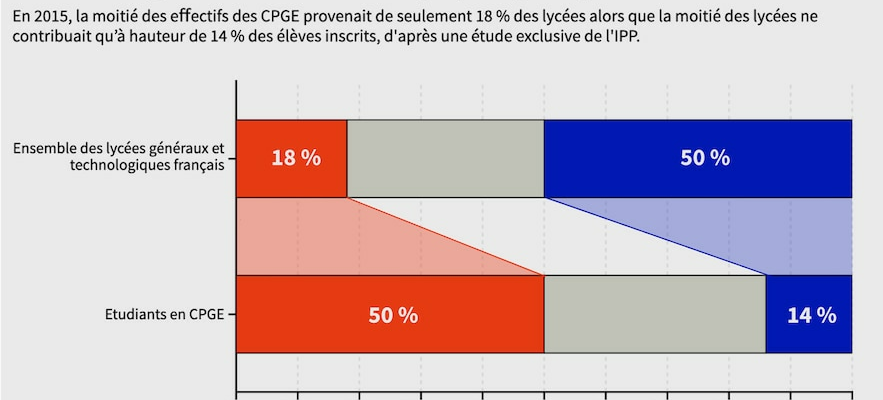

A note from the Institute of Public Policy, to be published on March 25 and that L’Express was able to consult exclusively, looked at the offer of preparatory classes to the grandes écoles (CPGE) and higher technician sections (STS) in the territory, between 2006 and 2015. Half of the general and technological high schools only provide a quarter of the workforce of these so -called “proximity selective training. The latter, although they offer interesting outlets, are therefore far from accessible everywhere. However, the offer is progressing, especially in small towns. “The fact that these training courses can be sheltered by infrastructure already in place such as high schools limits the opening costs. This is one of the advantages of this public policy,” explains Georgia Thebault, the author of the study.

A handful of secondary establishments provides most of the CPGE workforce, according to the PPI.

© / Mathias Penguilly / L’Express

Lucie, 22, student in a master’s degree in communication of organizations at the Sorbonne Paris Nord has also failed to give up her initial ambitions. Originally from a small village located thirty minutes from Nîmes, in the Gard, she first plans to follow her studies in Montpellier. “It represented a two-hour door to door. Impossible to go back and forth every day. I told myself that I would be more likely to find accommodation provided by the CROUS by winning the capital,” explains the girl who obtains a right room, just a week from the start of the lessons.

The track which consists in promoting the establishment of universities and schools everywhere in the territory, however, has its limits. In some places, the local training offer “can only be of limited scale to the workforce concerned”, recognizes the Court of Auditors. Among its recommendations: strengthen the weight of the criterion of geographic distance in the calculation of scholarships. But also simplify the methods of payment of aid to students via the creation of a one -stop shop. The regional centers of university and school works (Crous) which offer 175,000 dwellings on the territory have intensified their efforts in recent years. “From 2013 to 2022, the State invested 600 million euros to create 65,000 additional dwellings. And, since 2017, a billion euros has been devoted to the rehabilitation of 23,000 beds,” explains Bérand Durand, president of the CUSS who pilots the network. However, the park only welcomes 7 % of all students today. The vast majority of students must go hunting for small areas on a saturated rental market where prices fly away.

“In Ariège, we only talked about Toulouse!”

“The subject concerns both the Crous and the social landlords, the private actors but also the local authorities. The establishment of coordination bodies of all these actors is absolutely essential if we want to accelerate the movement”, insists Bénédicte Durand. For Amandine Simard, the subject must also be treated much further upstream, from secondary school classes. “In my Lycée Ariègeois, the teachers only spoke to us about Toulouse, the closest big city. As if our horizon was only reduced. I would have liked to be better accompanied in my orientation project,” explains the young woman.

Arriving in Paris, while she finds herself immersed in administrative meanders in the hope of winning a room, she comes up against the misunderstanding of a social worker. “‘But finally, why did you come to Paris if you can’t afford it?’ She asked me. As if I were not allowed to access a prestigious Parisian training, I who have always been a good student!”, She exclaims. Today, the young woman is at the head of the Ariège association with the grandes écoles: “Young people are far too many to give up their dreams for fear of not finding a roof. It is up to them to show them that it is possible.”

.