Since the end of the grain agreement unilaterally decreed by Russia on July 17, Ukraine can no longer safely export its grain through the Black Sea. To get around the Russian army’s blockade and sell their cereal production, which is essential to global food security, the Ukrainians had to find alternatives.

With production that represented nearly 20% of its economy and 41% of its exports before the outbreak of war with Russia in February 2022, the agricultural sector is absolutely essential to the survival of the Ukrainian economy. This did not escape Moscow which, from the first days of the conflict, had launched a maritime blockade on Ukrainian ports to prevent exports and cut off kyiv from a large part of its income.

Faced with pressure from the international community and the dangers that the blockade posed to global food security, Russia finally agreed to sign with Ukraine, in July 2022, an international agreement under the aegis of Turkey and the UN to allow the export of Ukrainian grain through the Black Sea. In one year, nearly 33 million tonnes of cereals were able to leave the ports of OdessaChornomorsk and Yuzhnyi, thus avoiding a food crisis which threatened many countries in Africa and the Mediterranean region.

The agreement, known as the “Black Sea grain initiative”, was ultimately not renewed by Moscow, for which the Black Sea became once again de facto “ a risk area “. This is not enough to discourage the Ukrainians who for almost two years have multiplied the alternatives for exporting their cereals. RFI takes stock of the alternative routes used by Ukraine to export its cereals.

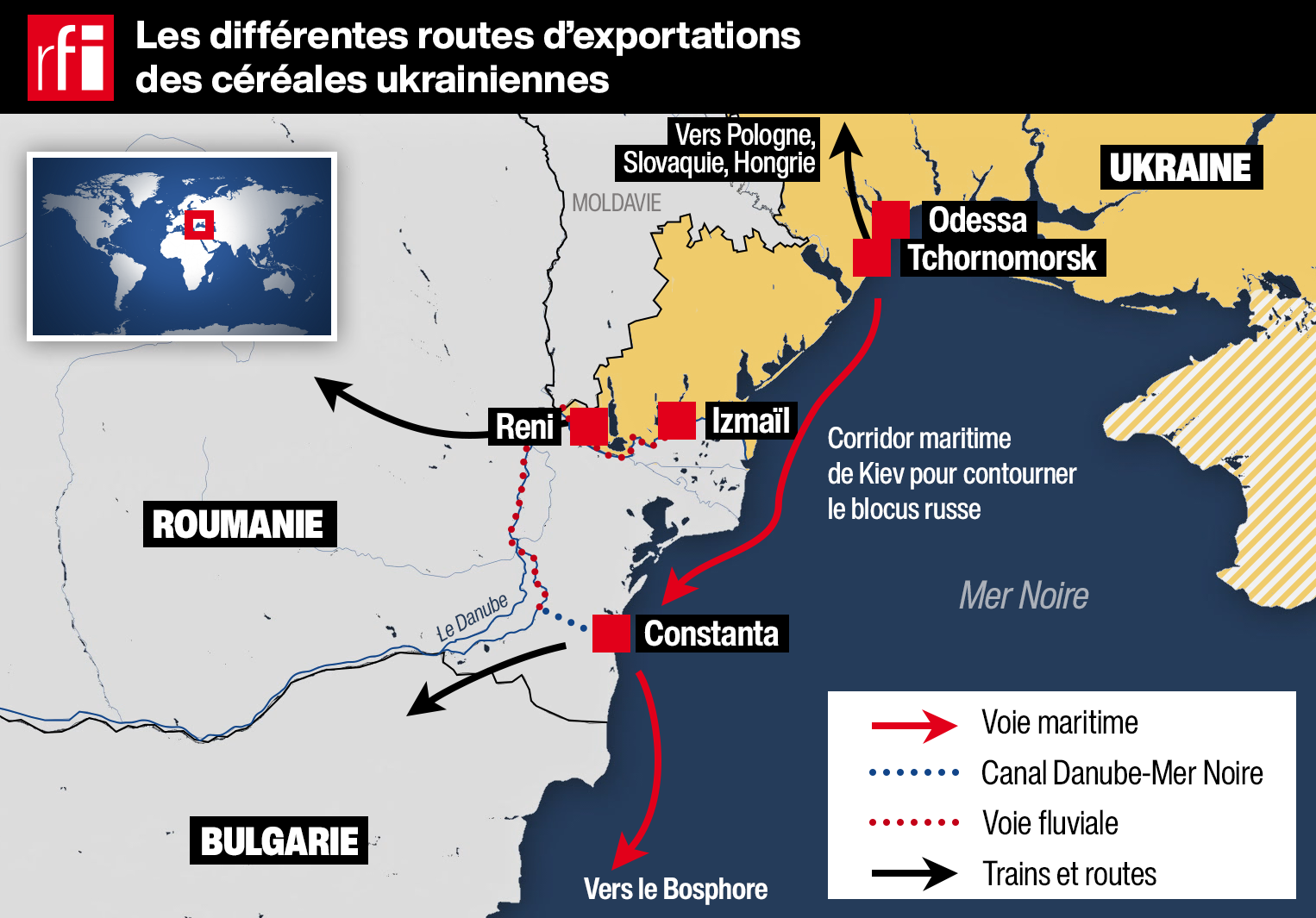

Despite Moscow’s threats to attack all boats entering and leaving Ukraine, kyiv seems determined to continue using the sea route to export its grain with or without Russian agreement. For the first time since the end of the grain agreement, a cargo ship loaded with 3,000 tonnes of Ukrainian wheat left the port of Chornomorsk to reach the Bosphorus Strait on Thursday September 21. A second freighter also made the same journey Sunday September 24 with, on board, 17,600 tonnes of wheat destined for Egypt.

kyiv is thus seeking to open a new maritime corridor along the western coasts of the Black Sea to circumvent the Russian blockade. The ships skirt the Ukrainian coasts but also, and above all, the coasts of Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey in order to dissuade Russia from attacking these boats in the territorial waters of NATO member countries. The United Kingdom also claimed that British warplanes were protecting cargo ships during the crossing in order to be ready to respond in the event of a Russian attack.

“ Is it sustainable? The future will tell. If boats do not sink, there will be a precedent and this could be repeated, estimates Alexandre Marie, chief analyst at Agritel-Argus Média France, a firm specializing in the analysis of agricultural markets. For the moment it is rather anecdotal, we are on an epiphenomenon. But psychologically, it is important. »

Odessa’s deep-water ports have a monthly grain export capacity of approximately 4.5 million tonnes, slightly more than equivalent to the capacity of alternative river and land routes. If Ukraine wants to maintain its trade balance and earn foreign currency, it has every interest in continuing to circumvent the Russian blockade in the Black Sea. This nevertheless poses insurance concerns for shipowners, which causes the price of transport to skyrocket. However, we must expect kyiv to repeat the experience; three boats should attempt to cross it to the Bosphorus in the coming days.

The river route via the Danube

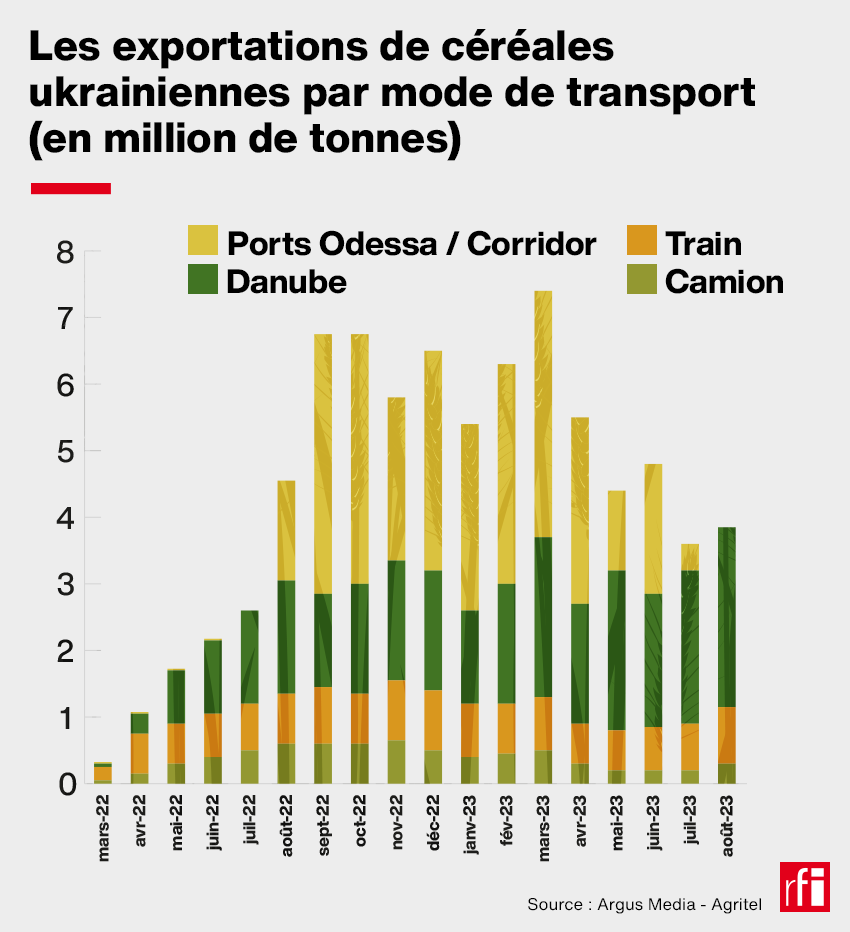

Since the start of the blockade in 2022, the river route which consists of passing through the Danube starting from the two largest Ukrainian inland ports, Reni and Izmail, has been the number one alternative to avoid the Russian threat in the Black Sea. Even during the implementation of the grain deal, the route remained particularly busy, particularly because the inspection of each ship required by Russia caused significant delays for cargo ships. In 2022, the quantity of grain to transit the Danube increased from 1.4 to up to 2.2 million tonnes per month. So much so that in May and June 2023, the tonnage of cereals to be transported by the river was greater than that using the cereal corridor still in force at the time.

According to Alexandre Marie, the maximum capacity of the river route could potentially reach “ 2.5 million tonnes of grain per mes”, but transporting Ukrainian grain across the Danube cannot be done without encountering a certain number of logistical problems. The width of the river requires the use of boats with a much smaller capacity to go up the river and transport grain cargoes to Constanta, via the Danube-Black Sea canal which provides access to the first Romanian port of where grain can be loaded onto larger ships. They can then safely reach the Bosphorus Strait or be sent to the rest of Europe by land via train or trucks.

This route is safer, but also slower. And Russia, which has understood its importance for the Ukrainian economy, no longer hesitates to target the Danube ports. Since the end of the grain agreement, the port infrastructures of Reni and Izmaïl have regularly been the target of drone attacks despite their very close proximity to the Romanian border.

“ The Danube is a temporary alternative, but does not replace the loading capacity offered by all ports [en eaux profondes, NDLR] from the Odessa region. Before the war, these made it possible to export quantities three times larger than what passes today via the Danube », explained to RFI Gautier Le Molgat, the director of the Agritel firm. During the grain agreement, Ukraine could export between 7 or 8 million tonnes each month, with the end of the agreement these exports fell by half, to around 4 million tonnes per month.

Read alsoUkrainian grain: “The Danube is not enough to replace the Black Sea ports”

The land route with train and trucks

This is the third alternative for Ukrainian grain. From the start of the war, Ukraine and its European allies did everything possible to develop grain exports by train and road. The European Union, for example, launched solidarity corridors to allow Ukraine to export its cereals by lifting customs duties and quotas.

Nearly a million tonnes of grain cross the borders of countries bordering Ukraine (Poland, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria and Slovakia) each month via rail. At the same time, 500,000 tonnes are also exported monthly by truck. “ Of the 4 million tonnes exported via alternative routes, we have approximately 2.2 million tonnes which pass via the Danube, a large million tonnes which pass by train and the maximum which was carried out by truck represented 700 000 tons. So in total, if we add the maximum capacity of the Danube which is around 300,000 tonnes more, we can reach 4.3 million tonnes monthly. », summarizes Alexandre Marie.

But going by land is also not without logistical problems, particularly because the Ukrainian railways dating from the Soviet era are 85 mm wider than in Europe. This therefore involves transshipping cargo from one train to another once arriving at the border.

Furthermore, the storage of large quantities of cereals in countries bordering Ukraine is beginning to arouse the anger of local farmers and diplomatic tensions between Kiev and some of its allies, because it leads to a drop in prices and, according to them, generates a unfair competition since Ukrainian cereals are not subject to European Union agricultural rules. In May 2023, while the Black Sea grain deal was still in force, the European Commission imposed an embargo on Ukrainian grain in five countries: Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria. Expiring on September 15, several countries including Poland have decided to extend this embargo, angering Kiev.

To end the diplomatic crisis brewing between Ukraine and one of its closest allies, Polish President Andrzej Duda reached a compromise: the sale of Ukrainian grain in Poland remains prohibited but the authorities have announced a floor on opening of corridors to allow their transit across the country. “ We must do everything to ensure that the transit of Ukrainian grain is as high as possible “, said Andrzej Duda.

What is exported and to which countries?

Of the 33 million tonnes of grain exported through the Black Sea grain deal, almost 51% was corn, 27% wheat and 10% sunflower products. Nearly 65% of this wheat was exported to developing countries compared to 51% of corn. Egypt, Tunisia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Morocco, Sudan and Algeria were among the main African beneficiaries of these exports which they were also able to re-export to other countries on the continent.

The United Nations World Food Program (WFP) also transported wheat from Black Sea ports. Until July 2023, the program has purchased 80% of its grain stock from Ukraine, compared to 50% before the war. During the period of implementation of the initiative, more than 725,000 tons of wheat left Ukrainian ports bound for Ethiopia, Yemen, Afghanistan, Sudan, Somalia, Kenya and Djibouti.

If the grain initiative in the Black Sea had, among other things, the objective of avoiding a global food crisis, the end of the agreement does not call into question “ the supply of countries where food inflation is a real issue because the alternatives are there, believes Alexandre Marie. Exports of large exporters are not affected by the slowed export flow in Ukraine. Russia has greatly expanded its market share. Worse than that, Europe is today behind in its exports given of the Russian competition “.

If at the start of the implementation of the agreement in July 2022, corn left Ukrainian ports in large quantities, today the situation has changed. The wheat season is coming to an end and the corn harvest will soon begin. Ukraine must therefore continue to export its wheat to free up space in its grain silos to accommodate corn.

But using alternative river and land routes to export these cereals has a significant cost. “ Logistics is very expensive. The other side of the coin is prices paid to farmers which are well below the world market, because all logistical costs must be amortized. The price paid to farmers is clearly below production costs for cereals, analyzes Alexandre Marie. This is where the big questions arise for the future: will producers be resilient enough to continue producing for the next harvest? “.