On October 22, Brian Niccol undertakes an unprecedented exercise by presenting the quarterly results of the company he has been managing for several weeks. While baristas prepare coffees in the background, the fifty-year-old stands in front of the camera, a serene smile on his lips. “People love Starbucks,” he says. Before moving on to a bitter observation: “But I have heard clients tell me that we have moved away from what makes up our soul.”

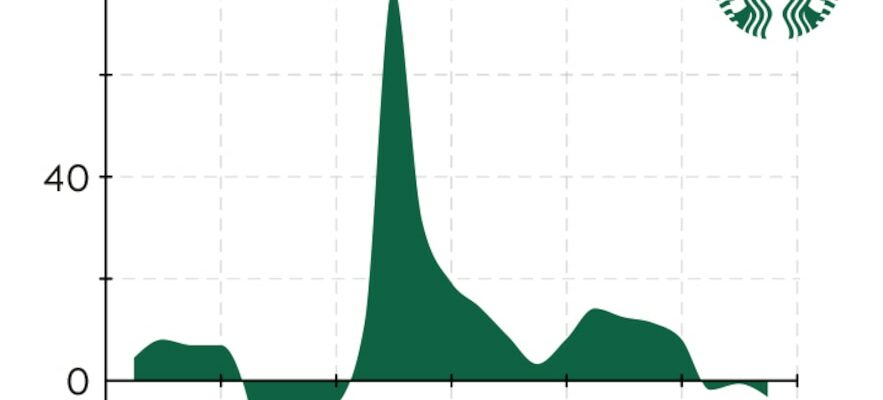

It must be said that the brand with the green mermaid is going through a delicate period. For the third consecutive quarter, its financial performance disappoints. Over the period from July to September, North American cafes saw their sales decline by 6%, on a number of comparable stores. In China, its second largest market, they fell by 14%. Even the return of its iconic creation, the Pumpkin Spice Latte, was not enough to reverse the trend.

Thanks to its whimsical drinks and cozy interiors, Starbucks has built a veritable empire: more than 40,000 cafes worldwide and 36 billion dollars in turnover. But the multinational is now mired in a series of dilemmas. Personalization or speed? Local experience or digitalization? High-end or mass clientele? The group’s historic boss, Howard Schultz, does not mince his words: in a LinkedIn post last May, he asserts that Starbucks has “fallen from grace”.

Italian inspiration

If the former CEO allows himself to be so critical, it is because he dedicated four decades to this company. “Schultz is a visionary, it is thanks to him that the phenomenal expansion of Starbucks began,” recalls John Simmons, author of The Starbucks Story: How the brand changed the world. The saga of the coffee juggernaut began in Seattle in the 1970s, with a group of three friends dreaming of offering America the quality of roasted coffee beans. The adventure begins with a small store, called Starbucks, in reference to a character in the novel. Moby-Dick. The arrival of Howard Schultz, a few years later, marked the beginning of a success story.

During a trip to Milan, this young entrepreneur fell under the spell of the finesse of espresso and decides to export the art of drinking “Italian” coffee. Upon his return across the Atlantic, the three founding friends of Starbucks were perplexed by his expansion plans. He then created his own café, which he named Il Giornale, before buying Starbucks a few years later and merging the two companies. To this day, the sizes of the cups are still designated in Italian – a nod to his Milanese journey.

In the 1990s, the brand decided to position itself as a marker of social status. “They opened cafes on Wall Street, in the wealthy suburbs, thus putting their logo on the path of rich consumers,” Bryant Simon, history professor and author ofEverything but the Coffee: Learning about America from Starbucks. But their base of followers does not take long to expand. “Less wealthy customers say to themselves, ‘Me too, I want to have this status,’ because ultimately, a cup of coffee is not as expensive as a BMW or a villa to convey an image of prestige,” concludes the author. . Brands are opening in shopping centers and airports – a strategic positioning that always guarantees them passage. The brand becomes more accessible, but loses its selective aspect.

The tireless Howard Schultz took over the reins of the group in 2008, after a brief break, while Starbucks suffered the consequences of the crisis. A few years are enough to straighten out the accounts. And for good reason, Schultz goes to great lengths, not hesitating to close some 7,000 cafes for an afternoon to train the teams in “the art of the perfect espresso“. A return to basics.

The group’s performance has recently deteriorated.

© / The Express

Third space

If coffee is the heart of its business, the brand also promotes its identity as a “third space” – halfway between the workplace and the home – offering, before others, a Wi-Fi connection and the possibility of install with a computer. “Starbucks focuses on the idea of offering a warm and relaxing environment, where people feel comfortable to work or meet,” explains John Simmons. “Whether you are in Paris or Tokyo, it’s a place where you know what to expect, both in terms of products and atmosphere,” adds John Plassard, director at the private bank. Mirabaud and a fine connoisseur of American firms.

The “Seattle mermaid” also relies on individualized marketing. The name of each customer is scribbled on the cup, and hundreds of combinations are possible to make their drink, juggling as desired with different syrups, milks, sizes and temperatures. “Starbucks was able to offer drinks that no other coffee shop could compete with. But it became an obsession with making ever more daring and multi-colored drinks that people could take photos of to feed their Instagram accounts,” observes Bryant Simon .

Between frappuccinos, teas and other lattes, the plethora of offerings lengthens service time, to the detriment of the customer experience. Starbucks is trying to remedy this by implementing an optimized and partly digitalized process, intended to reduce preparation time by more than half. However, “this strategy has rather damaged the image of the brand than really stimulated sales. Certainly, the service is more fluid, but that does not distinguish it from that of a fast food restaurant”, notes Christian Parisot, economic advisor for Aurel BGC.

Missed turn

Starbucks’ disappointing financial results further reflect a missed turn at the end of Covid, analyzes B. Joseph Pine II, theoretician of the concept of “experience economy”. With nearly a third of its orders now placed online, the American giant is gradually moving away from its original concept, that of a friendly café and a place of exchange. “Starbucks got excited about falling costs at the end of the pandemic, in particular by going all out on mobile orders,” notes the American economist.

Result: queues have lengthened, servers now having to deal with both on-site consumers and remote sales. “For many people, going to a Starbucks is no longer worth it if invisible customers walk past you in line,” points out B. Joseph Pine II. “The majority of sales are made in the morning, and a few extra minutes of waiting can be critical,” adds Sharon Zackfia, analyst at the investment bank William Blair.

This drop in attendance is part of a broader trend of slowing demand, due to inflation. However, this decline is not just a question of price: “Many Americans are willing to spend $8 on their drink. But for that price, they want to be served quickly and have the barista smile at them. Price and l “experience goes hand in hand,” continues Sharon Zackfia.

Other factors explain the group’s difficulties: the increase in coffee prices in recent years, the rise in labor costs and rents have weighed on margins, notes John Plassard. Recently, the reputation of the multinational has also been shaken by controversies surrounding the private jet and the salary of its new boss, as well as by boycotts on social networks linked to an alleged position in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Competitors

Above all, Starbucks is no longer alone in the coffee market. The brand is today squeezed by two types of competitors. At the bottom, fast food chains, such as McDonald’s or Dunkin’, which have reduced their prices to attract thrifty customers. “Starbucks has lagged behind aggressive low-price campaigns, such as the $5 menus implemented by fast-food restaurants,” notes Christian Parisot. At the top, the abundance of independent cafes which appeal to some of its fans. “These establishments focus on superior quality products and artisanal preparation. Ironically, they compete with Starbucks on its initial identity,” observes Noa Berger, sociologist specializing in coffee.

Faced with these premium rivals, Starbucks would benefit from highlighting its “accessible” character, judges Noa Berger. “What makes Starbucks strong is the diversity of its customers and the fact that everyone feels comfortable there. An executive, a tourist or a young person can sit on a sofa and sip his drink,” she analyzes.

China, finally, is an essential market for the brand: in 2017, Starbucks announced that it would open a new store there every fifteen hours. The group now has some 7,000 cafes in the country. But the slowdown in the Chinese economy and strong competitive pressure are putting this segment of the business at risk. Local chains, such as Luckin Coffee or Cotti Coffee, have seen their popularity explode in recent years among Chinese customers. Added to this are a multitude of small players who offer home delivery and often lower prices.

“Back to Starbucks”

The profile of the new CEO, Brian Niccol, called to the rescue this summer, gave hope to the financial markets: the stock rose 25% following his appointment. The businessman has already proven himself by transforming the image of the fast food chain Taco Bell, then by boosting the profits of its counterpart Chipotle. “If anyone can solve Starbucks’ problems, other than Schultz, it’s Niccol. It’s just a question of cost and time,” enthuses Sharon Zackfia.

To turn things around, Brian Niccol has a plan. Entitled “Back to Starbucks”, it sets itself the objective of reconnecting with the essence of the group: a “community coffee house”. No more long menus and traffic jams at the checkout. Niccol wants the return of ceramic cups for on-site consumption, and a waiting time of less than four minutes. “The new priority is to create more added value and encourage customers to stay longer in the premises,” analyzes Christian Parisot. All while refocusing on the American market.

A marketing challenge summarized in these terms by Bryant Simon: “Maintain a positioning that aims to be high-end while addressing an ever-broader customer base.” The delicate exercise will require rediscovering the “soul of Starbucks”, so dear to Howard Schultz.

.