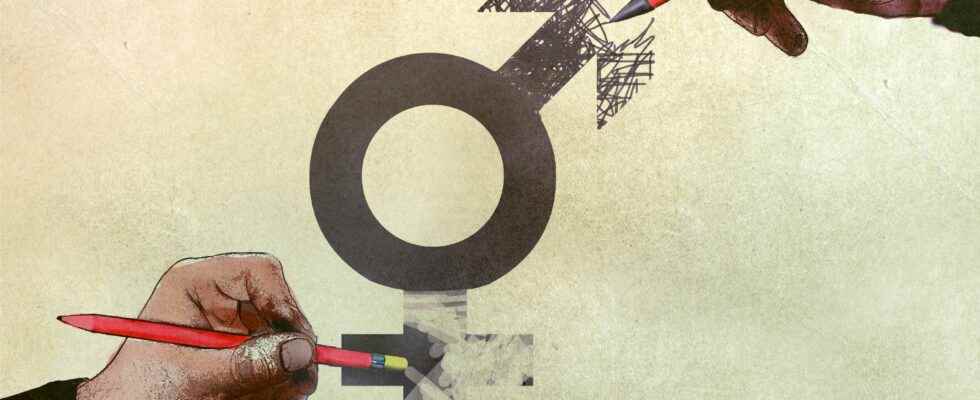

Between those who fiercely defend that there are only two sexes and those who believe that there are three, five or more, the debates follow one another and are similar in their inability to lead to common ground. Unfortunately, these debates are insoluble, because the meaning of words is only a convention, and words in everyday language often have several meanings. This is the case of the word sex. Even from a strictly biological point of view, the word sex has several meanings.

The most fundamental meaning, which induces all the others, is that of the reproductive role. In mammals, there are only two reproductive roles. One is to produce small gametes (reproductive cells), the spermatozoa, it is called the male sex. The other consisting in producing large gametes, the oocytes, is called the female sex. No other reproductive role exists, and from this point of view, therefore, sex is perfectly binary. The story could end there, if evolution had provided us with mechanisms to assign each organism a sex infallibly. But it has given us biological mechanisms of sex determination of great complexity, which can fail in many ways.

Genetically, sex is determined by the SRY gene

At the genetic level, everyone knows that sex is coded by the sex chromosomes: XX for female and XY for male. But there are other possible combinations: X, XXY, XYY for the simplest. And sex is actually determined by a single gene (SRY), normally carried by the Y chromosome, but sometimes copied onto an X chromosome, and this gene sometimes undergoes mutations that modify its function. Thus, the chromosomal sex has been selected to be binary, but admits rare exceptions. In the presence of a functional SRY gene, the gonads (organs that produce gametes), initially undifferentiated in the embryo, develop in the male form: the testicles. In its absence, they develop in the female form: the ovaries. But despite a strictly binary model, this gonadal sex can adopt various very rare intermediate forms.

The testicles and the ovaries produce different sex hormones which will induce a cascade of transformations in the body, including the differentiation of the genital organs: prostate, penis and scrotum for males; uterus, vagina and vulva for females. This is the phenotypic or anatomical sex. Here again, multiple genetic or hormonal variations can deviate the differentiation between the 2 canonical forms towards intermediate forms. It is on the imperfect basis of this phenotypic sex, observed at birth, that legal sex is assigned (in the civil register). It is sometimes authoritative, when the external genitalia are ambiguous. And this attribution is necessarily unsatisfactory for the intermediate cases, which do not correspond to either of the two boxes.

Finally, in about 99% of humans, the chromosomal, gonadal and phenotypic sexes have a male or female form, and concur with each other. In 1% of us, at least one of these sexes may have an intermediate or ambiguous form, or be discordant with the others. There are a multiplicity of cases that are collectively referred to as intersex conditions.

To sum up, we could say that in mammals, at the level of function – that is to say reproduction -, and of design – that is, the forms that biological mechanisms have been selected to generate – sex is binary. But at the level of the realization, it is not quite. There is a whole continuum between typical male and female forms.

Gender identity, sexual orientation and gender expression

In addition to these biological characteristics, there are cognitive characteristics associated with sex, such as gender identity, or feeling like a man, a woman, or somewhere in between. Or sexual orientation: being attracted exclusively or preferentially to men, women, both, or neither. Or even gender expression: behaving more or less in the way that is considered typical of a woman or a man in a given culture. These different characteristics clearly lie on a continuum between the typically masculine and feminine poles.

From these multiple concepts and their definitions, everyone makes their market: some say “sex” thinking of the reproductive role, others of the chromosomes, still others of the genital organs and their multiple forms. No wonder they can’t find the same number. To add to the confusion, some use the word sex to refer to gender: typically, people who do not perceive the difference between the two, and who equate all feminine and masculine characteristics with biological sex. Others use the word gender to designate sex: typically, people who consider that “everything is social” and who want to hide the biological dimension of sex. All the ingredients are thus gathered for misunderstandings, imprecations, invectives, accusations…

To avoid sterile disputes, it would be healthy to know the different definitions, to specify which meaning of the word sex we use, and to know how to recognize when we use a different meaning from our interlocutor. The distinction between sex and gender is important. Rather than rejecting an imaginary “gender theory” outright, let’s give credit to gender studies for helping to distinguish these important concepts. And let us be wary of discourses tending to amalgamate them with the aim of concealing either the biological dimension of sex or the social dimension of gender.

Franck Ramus is a research director (CNRS), he works at the Laboratory of Cognitive Sciences and Psycholinguistics (ENS), and is also a member of the Scientific Council of National Education.