On March 29, 2022, Elon Musk received an SMS from an associate professor at Oxford offering to put him in touch with an investor “potentially interested in buying Twitter to do something beneficial for the world”. Reply from the American billionaire: “Does he have a lot of funds?” “It all depends on how you define ‘a lot’! He has 24 billion dollars”, replies his interlocutor, before reassuring him: the investor is “very involved in the idea of improving the future of humanity “.

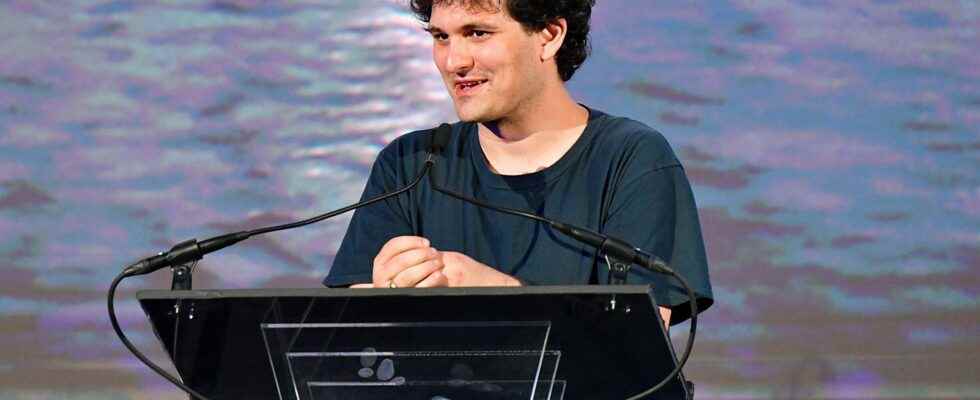

Seven months later, Elon Musk did indeed come into possession of Twitter at the end of October. The “potentially interested” but ultimately not associated with the takeover, investor Sam Bankman-Fried, has just been swept away by the possibly fraudulent bankruptcy of his cryptocurrency exchange platform, FTX, and has been arrested in the Bahamas. The intermediary, the young British philosopher William MacAskill, had to publicly disentangle himself from his association with him, expressing his “absolute anger”, his “sadness” and his “mortification” if ever the accusations were confirmed.

Ten years ago, Scotsman MacAskill had, over lunch, convinced Bankman-Fried, then a young student at MIT, that his best way to contribute to the good of humanity would be to adopt the “earning to give” credo, that is to say to pursue a career in finance while donating a considerable proportion of its income to philanthropic causes. “Work in a field that you love and where you excel and, even if this work in itself does not have a gigantic impact, you can have a huge impact by giving money”, he summarizes in his new book, What We Owe the Future, a French translation of which is planned for next year. An essay in which the author claims to have invested the equivalent of “more than ten years” of full-time collective work, with six research assistants and dozens of experts consulted.

The daredevil teenager and the responsible hiker

The affair disrupted the Hollywood promotion plan for this bestseller, whose actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt, friend of the author, affirms on the back cover that his “optimistic vision of the future” “moved him to tears”, and where a certain Elon Musk sees “a philosophy very close to the [sienne]”. And which constitutes both a theoretical essay but also a practical, even political, roadmap for a movement of which MacAskill is one of the spearheads: “long-termism”.

From his first sentence, the philosopher invites his reader to engage in a “thought experiment”: “Imagine living, in order of birth, the life of all the human beings who have ever lived”, that is to say a hundred billion people altogether. But the world will see many more appear in the future, at least if we manage to ensure the survival of our species. As summed up by one of MacAskill’s thought brothers, Toby Ord, in a book called The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity (2020), “our generation is just one page in a much longer narrative”. To illustrate it pictorially, the author of What We Owe the Future he chooses to blacken entire pages, precisely, with a series of small pictograms each symbolizing ten billion people, a little more than the current world population. After four pages, he stops the exercise to point out that this tight alignment of silhouettes represents only a tiny fraction of the colossal number of humans to be born if our species ever survives for “five hundred million years”.

Humans to whom we have a duty: “If humanity survives even a fraction of its potential lifespan, then, strange as it may seem, we are the ancients: we are at the very beginning of history, in the most distant past. What we do now will affect countless people in the future. We must act wisely.” Humanity can behave like a daredevil teenager who, like the author himself, ran mortal risks by indulging in urban climbing. Conversely, she can act as a responsible hiker who, accidentally breaking a bottle on a trail, picks up the pieces to prevent someone from getting hurt in the future.

Millions, billions and trillions of years

Before becoming the herald of “long-termism”, MacAskill is known to have given birth to a movement called “efficient altruism”, based on a utilitarian calculation of the same kind as that praised to Sam Bankman-Fried: you are much more competent in finance than in natural sciences but dream of saving lives in poor countries? Rather than opting for humanitarian medicine, become an investment banker and pay half of your income to an NGO.

This mathematics of choice is also found in long-termism: the philosopher compares our approach to the promises and dangers of the future (pure and simple extinction but also civilizational decline, nuclear or biological war, global warming, the taking of control of a malevolent artificial intelligence…) to that of the poker player who calculates in his head the probabilities that the next cards will give him a winning or losing hand. In The Long View, another plea for this philosophy published collectively last year, MacAskill, marked by the impact on popular consciousness of disaster films like Deep Impact and Armageddon, makes the following calculation: if investing 20 billion dollars in an asteroid deflection device makes it possible to reduce the probability of a collision with the Earth by 0.0001% to 0.00005%, this is equivalent to an average of 50 millions of lives saved over a time horizon of one billion years, or $400 per lifetime. A cost per “head” far below that of most short-term humanitarian interventions.

Arbitration recalls, in a cosmic mode, the ethical debates around the famous “tram dilemma” : if a tram is about to run over five people and I can deviate its trajectory so that it runs over another one, and only one, what is the moral decision to adopt? If an investment preserves a massive number of existences in the long term, should I prefer it to another much less profitable short-term oriented one? Yes, answers one of the currents, said “radical”, of long-termism, of which one of the most famous representatives is the philosopher Nick Beckstead. In his doctoral thesis, defended in 2013 and devoted to the “colossal importance of the construction of the distant future”, that is to say the “millions, billions and trillions of years” to come, the latter advocated “fanaticism “, the fact of preferring the tiny probability of an infinite gain to the greater probability of a limited gain. At the end of 2021, Nick Beckstead was appointed by Sam Bankman-Fried to head the FTX Future Fund, a philanthropic fund backed by FTX in which William MacAskill acted as advisor. Among the fund’s areas of interest were the prevention of future pandemics, research on vaccines or on food supplies in the event of a nuclear winter, the development of diagnostics using CRISPR technology, but also the “governance of the space”.

Spatial colonization and electoral ambitions

“Long-termism” has thus found itself associated with projects with a very… distant horizon, such as space colonization, a hobby of Elon Musk on which MacAskill is cautious: “We should focus on disasters who threaten us in the century to come in order to keep a chance of building a flourishing interstellar society for those who follow.” Among the possible drifts of the current is thus a mixture of frenzied techno-optimism and such a long-term vision that it becomes absurd. Professor at Cambridge, where he taught the “clearly brilliant” MacAskill during his first university years, the philosopher Arif Ahmed thus accuses long-termism doubly lacking in credibility: his preoccupation with abstract humanity disregards community attachments of all kinds, especially towards the generations that are close in time; its supposedly rational approach to dangers and benefits cruelly ignores the limits of long-term forecasting.

MacAskill himself acknowledges this at the beginning of his book, his philosophy resembles “a risky expedition into uncharted terrain. In our attempt to improve the future, we do not know exactly the threats we will face or even the exact place we are trying to reach; but, nevertheless, we can prepare”. In the last chapter, soberly titled “What to do”, the philosopher analyzes the advantages and limits of a series of behaviors: changing one’s individual habits, from recycling to vegetarianism; donate to organizations; or getting involved politically by voting or getting involved in a cause. Long-termism thus dreamed, at the beginning of November, of bringing one of its own into the American Congress, but its candidate for a representative seat in Oregon, Carrick Flynn, was sharply beaten in the Democratic primary, despite financial support. Sam Bankman-Fried Massif. During the campaign, this novice in politics had to respond to his opponents who described him, with reference to a famous film with Frank Sinatra, as a “manchurian candidate”. In other words, a puppet manipulated by interests as hidden as they are powerful, which try to shape the future in secret…