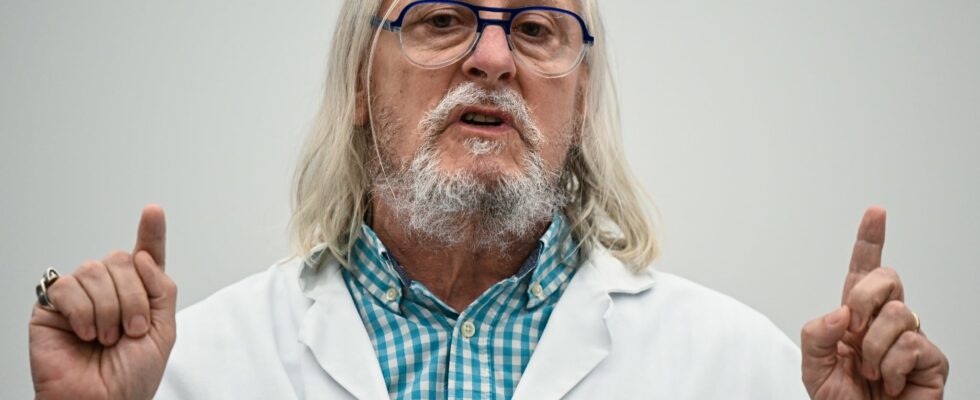

From Luc Montagnier to Didier Raoult, history is littered with brilliant minds who by certain standards appear to have great intelligence, but who have, in certain circumstances, failed miserably, their rationality seeming to have been obscured by belief unwavering in being right. Everyone can easily find other examples of apparent dissociation between an individual’s intelligence and their rationality.

It’s not just popular myths. For thirty years, eminent psychology researchers have theorized the idea that rationality is a quality independent of general intelligence and poorly measured by usual tests. Nobel Prize winner in economics Daniel Kahneman, recently deceased, has built his career on highlighting cognitive biases affecting human reasoning. He proposed that we reason using two independent cognitive systems. System 1, which produces intuitive, rapid responses adapted to the environment in which our ancestors evolved. And system 2, slower and more laborious, which allows us to take into account multiple and complex information and to make more elaborate and nuanced reasoning. Since System 1 often produces erroneous answers to the new and difficult problems that the modern world confronts us, rationality would depend on our ability to inhibit it and use System 2 wisely.

This line of thought has spawned a profusion of publications on the topic of “how can people who are so intelligent do such stupid things?”, as well as endless lists of cognitive biases. It has also fueled disdain for intelligence tests and IQ scores and led to the development of new “cognitive rationality” tests composed of small problems about which our intuitions are wrong. The question therefore arises whether these new tests measure something fundamentally different from general intelligence and whether they better predict rational behavior.

Intelligence gives no guarantee of being rational all the time

In fact, many studies have found that the rationality scores thus measured were particularly correlated with cognitive abilities. A meta-analysis of 44 studies established that common intelligence tests predicted up to 70% of individual differences in cognitive rationality. Moreover, a study based on pairs of twins suggests that the link between general intelligence and cognitive rationality is mainly due to common genetic factors. Finally, tests of cognitive rationality have failed to convincingly predict rational behavior beyond what intelligence scores already predict. Thus, as with the theory of multiple intelligences, the notion of general intelligence continues to resist the multiple assaults of alternative theories.

Of course, it remains true that one can be very intelligent and believe in nonsense or sometimes behave contrary to common sense. Intelligence only provides the means to be rational, but gives no guarantee of being so permanently. Even the most intelligent people remain subject to all human cognitive biases and not giving in to them requires constant vigilance. Anecdotes of intelligent people behaving stupidly will therefore never cease to amaze us, but they should not obscure general trends. The experimental results are clear: IQ scores measured by tests are the best predictor of the propensity to behave rationally.

This does not imply that we should give up teaching critical thinking and developing rationality in children, on the contrary! Cognitive abilities are not set in stone and good epistemic reflexes can be learned. If general intelligence does not entirely predict rationality, it is because it is necessary but not sufficient. Rationality additionally requires a great deal of knowledge about the world, an understanding of the scientific method, and the ability to evaluate the reliability of sources. To help teachers get to grips with this fairly recent part of school curricula, the scientific council of National Education has produced a summary of the researchassessment tools and educational resources.

Franck Ramus is research director at the CNRS in cognitive sciences